Security researchers have uncovered a firmware-level backdoor preinstalled on multiple Android tablet brands, raising urgent questions about the integrity of low-cost devices and the safety of buyers who never sideloaded a single shady app.

The threat, dubbed Keenadu by analysts, embeds itself deep in the operating system and quietly gains sweeping control over apps and data before the tablet even leaves the factory.

- What security researchers found in preinstalled malware

- Evidence of a supply chain breach in Android tablets

- Who is affected so far by the Keenadu backdoor

- How the Keenadu backdoor operates on Android

- Why budget Android tablet hardware is a soft target

- What users and IT teams should do to stay protected

- The bottom line on the Keenadu Android tablet threat

What security researchers found in preinstalled malware

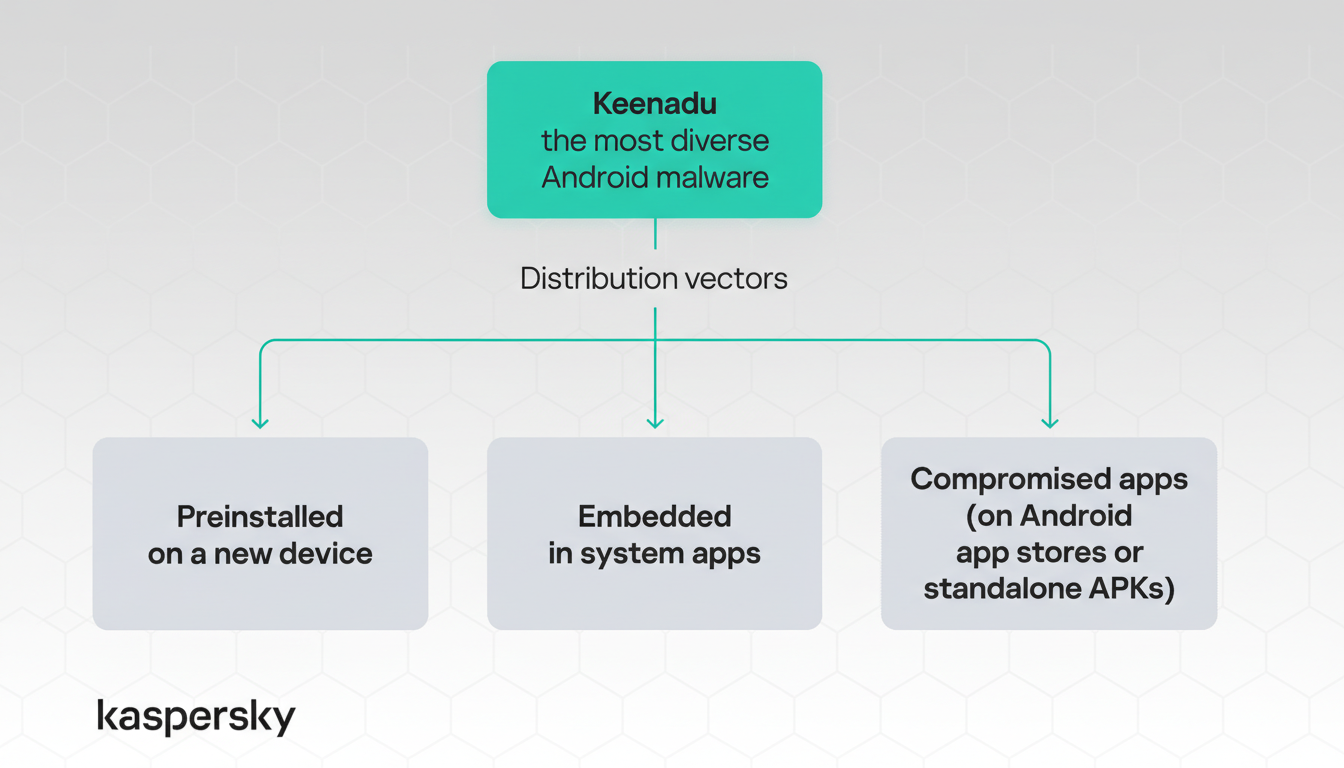

Kaspersky investigators report that Keenadu ships inside tablet firmware images from more than one manufacturer. Help Net Security highlighted the findings, which show the backdoor arriving as part of the official system build rather than through post-purchase infections.

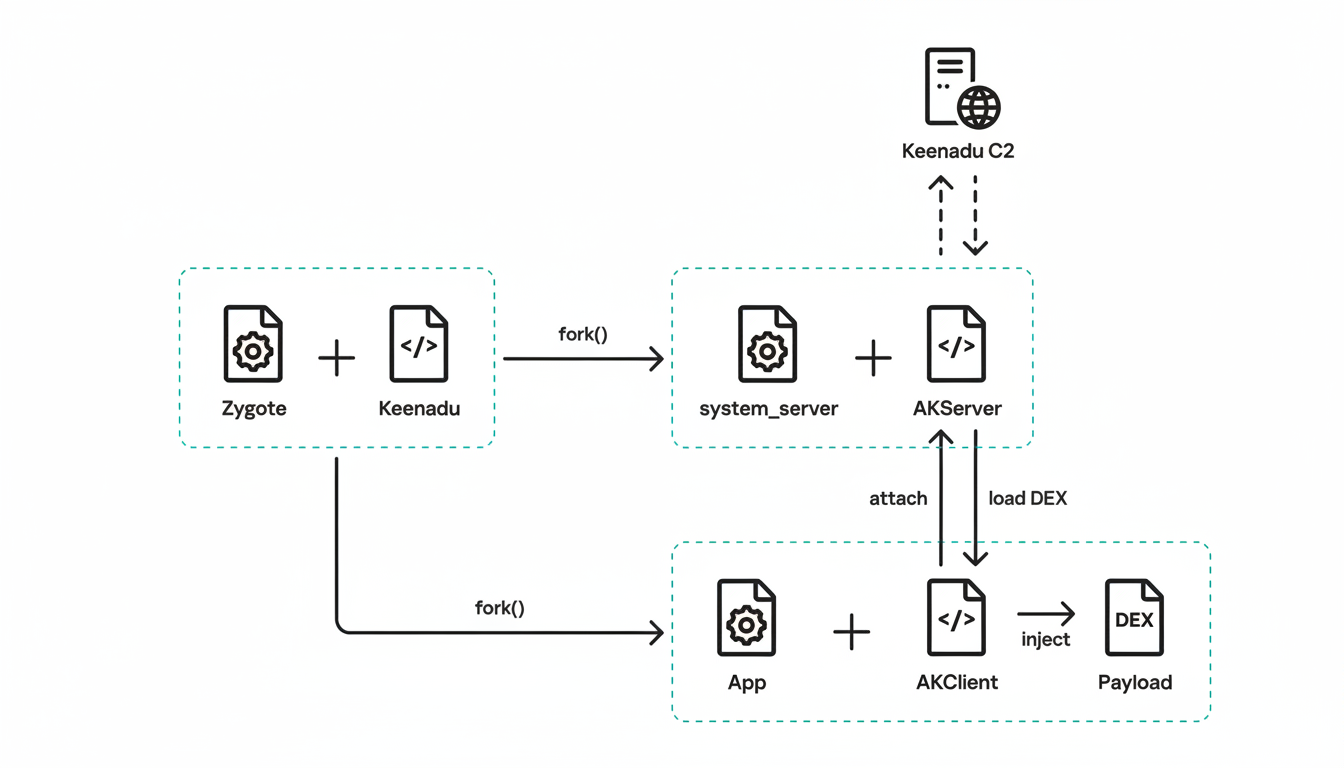

Once active, Keenadu injects into Android’s Zygote process—the component that spawns every user app. By hooking Zygote, the malware’s code can influence almost anything running on the device, from browser sessions to background services, with a level of reach that typical app-based malware can’t match.

Researchers observed Keenadu downloading additional modules that can redirect web searches, track app installations for affiliate payouts, and interact with advertising frameworks. These behaviors suggest a blend of monetization and potential botnet activity, not just nuisance adware.

Evidence of a supply chain breach in Android tablets

One confirmed case involves the Alldocube iPlay 50 mini Pro, where every examined firmware version contained the backdoor—even those released after initial malware reports. Crucially, images carried valid vendor signatures, indicating the problem was not a tampered over-the-air update but likely an upstream compromise during the build process.

That points to classic supply chain risk: malicious code embedded via compromised development environments, third-party components, or partner integrations used by original design manufacturers. Because the images are signed, Android’s Verified Boot treats them as trustworthy, and factory resets do not remove the threat.

Google’s Android security documentation has long warned that preinstalled threats are uniquely challenging, as they inherit system privileges and persistence that ordinary malware can’t achieve. Keenadu’s Zygote injection underscores how severe that advantage can be.

Who is affected so far by the Keenadu backdoor

Kaspersky says 13,715 users worldwide have encountered Keenadu or its related modules, with the largest concentrations seen in Russia, Japan, Germany, Brazil, and the Netherlands. The firm also links the activity to established Android botnet families, including Triada, BadBox, and Vo1d, suggesting code reuse or shared operator infrastructure.

Current evidence does not implicate major flagship brands. Impact appears centered on lesser-known or budget-focused vendors, and researchers note that affected manufacturers have been notified and are working on clean firmware.

How the Keenadu backdoor operates on Android

By injecting into Zygote, Keenadu ensures its hooks load into nearly every app process that starts, enabling surveillance or manipulation without obvious indicators. At that privilege level, it can intercept intents, observe browser queries, and install or trigger components that perform ad fraud or traffic hijacking.

Because Keenadu resides in signed system partitions, mobile antivirus tools and Google Play Protect may have limited visibility. Even if malicious modules are removed, the underlying backdoor can redownload them after reboot unless the base firmware is replaced.

Why budget Android tablet hardware is a soft target

Low-cost tablets often rely on complex manufacturing chains, turnkey firmware from third parties, and monetization SDKs added to squeeze revenue in tight-margin markets. That mix creates opportunities for a single compromised component to cascade across multiple brands that share the same reference designs.

Patch velocity is another strain point. Smaller vendors may lack robust incident response, allowing tainted builds to persist longer. Keenadu’s presence in subsequent signed releases illustrates how slow remediation can keep users exposed.

What users and IT teams should do to stay protected

- Check immediately for vendor firmware updates and install them. Look for release notes referencing security fixes or system integrity.

- Understand that factory resets won’t help if the malware lives in system partitions. Only a clean, vendor-signed firmware image can fully remove it.

- Use reputable mobile security apps to detect secondary modules and suspicious behavior while you await a firmware fix.

- In organizations and schools, restrict procurement to vetted brands with transparent update policies. Enforce device allowlists through an EMM, and audit network traffic for unusual ad click patterns, search redirections, or unexplained APK fetches.

- If your device exhibits persistent browser hijacks or reappearing adware despite resets, contact the vendor for a clean image or replacement.

The bottom line on the Keenadu Android tablet threat

Keenadu is a stark reminder that the most dangerous Android malware no longer depends on user mistakes. When the factory image is already compromised, defenses must move upstream—stronger supply chain controls for manufacturers, faster patch pipelines, and more cautious purchasing for buyers. Until clean firmware lands for every affected model, vigilance is the only viable mitigation.