Amazon is resuming its Prime Air drone deliveries in Arizona, following a crash earlier this week close to the company’s same-day facility in Tolleson. Two delivery drones hit the boom of a crane and crashed, causing operations to temporarily cease. Federal investigators are looking into the episode, and Amazon says its own review did not discover a systemic problem with the aircraft or the technology that helps support it.

Investigations and Safety Measures After Arizona Drone Crash

Both the National Transportation Safety Board and Federal Aviation Administration have opened inquiries, a normal process that usually includes acquiring telemetry, examining wreckage and reviewing airspace procedures. Amazon says it is fully cooperating and has already implemented new checks, including improved visual landscape inspections to see active obstacles like cranes more accurately.

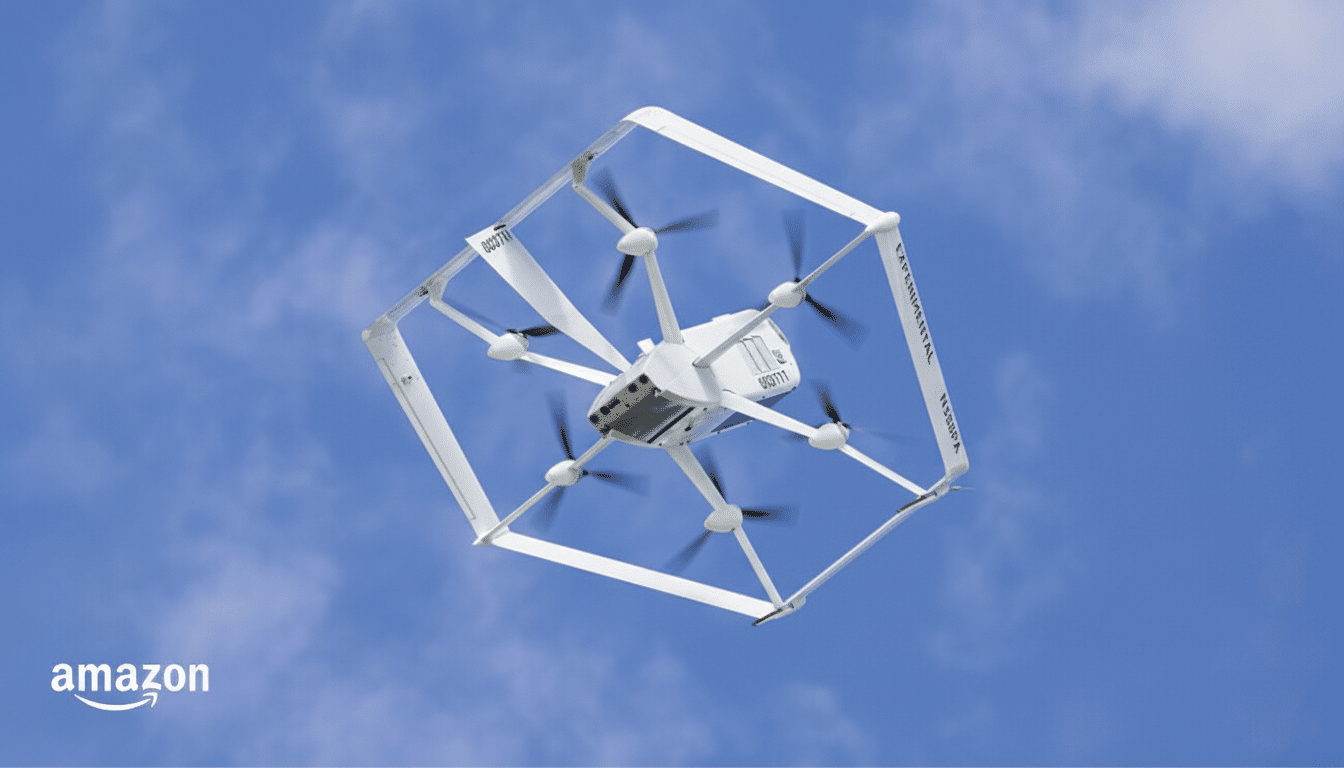

Dynamic obstacles are an ongoing challenge for low-altitude autonomy. Unlike buildings, cranes can change their height and position quickly, and they do not transmit their whereabouts electronically. That renders them harder to detect than aircraft with ADS-B or transponders, forcing operators to rely on a mixture of onboard perception, preflight scouting and cooperation with nearby construction sites.

Industry safety experts say that lessons from this type of episode tend to lead to improvements in geofencing, optical sensing and route planning. Investigators are likely to focus on the performance of detection and avoidance, operator procedures and any airspace notifications in effect at the time. The conclusions generally feed into a company safety case that the FAA requires for higher levels of operations.

What Happened and Why It Matters for Prime Air Safety

Two drones hit a crane originally, according to Amazon. While the crash site itself was at its West Valley site https://t.co/D5gax41adQ — Glenn Farley (@GlennFarleyK5), December 17, 2019. Apparently, the two drones hit a crane near our West Valley site. — Glenn Farley (@GlennFarleyK5), December 17, 2019. The event is not one of any larger pattern identified by the company, but it highlights the complexities of running autonomous aircraft in dynamic urban areas. Construction activity, temporary towers and event infrastructure can sprout up fast and alter the low-altitude risk picture.

Prime Air’s return to service seems to indicate that Amazon has confidence that incremental precautions will help prevent a recurrence. What the balance regulators are seeking to strike is how to keep a high safety bar while allowing operators to move beyond small test zones. Each such situation becomes one data point in that risk calculus.

Prime Air Footprint and Planned Expansion in U.S. Markets

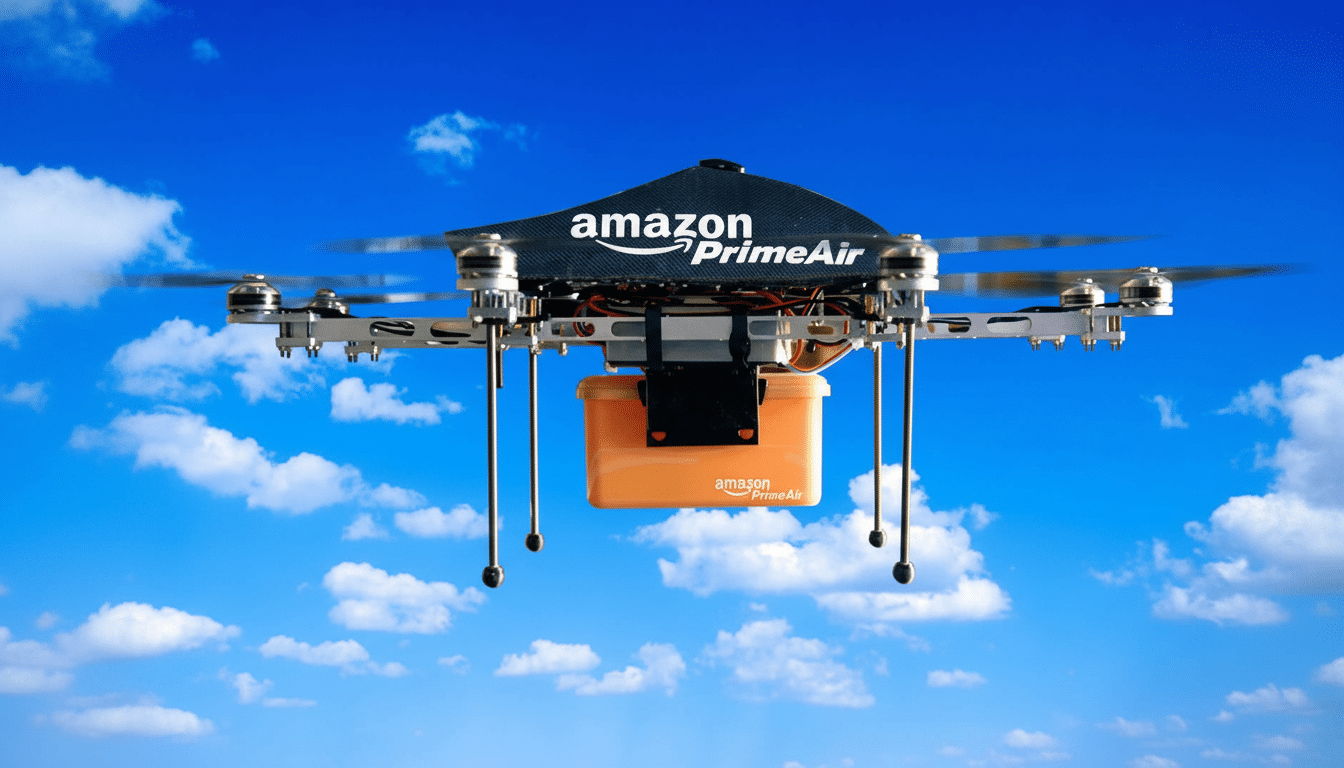

In its only known active commercial market, the West Valley of the Phoenix metro area, Amazon had been flying small packages — up to five pounds — by drone to select customers. The program has experienced fits and starts as the company worked out hardware, software and procedures.

A growth-enabling key occurred with an FAA-approved longer-distance route in specific circumstances, a movement toward larger beyond-visual-line-of-sight operations. Amazon announced its intentions to move into Texas markets like Richardson, San Antonio and Waco, and also listed Detroit and Kansas City as future locations — provided regulatory approvals can be attained in addition to community acceptance.

The company has set an ambitious goal of delivering hundreds of millions of packages by drone each year by the end of the decade. The context here is important: other players have built significant scale, with Zipline citing more than a million commercial deliveries worldwide, and Wing flying hundreds of thousands of trips in multiple countries. Amazon’s dominance in ground logistics is unmatched, but in aerial last-mile, it has yet to prove reliability and economic viability — not to mention acceptance by the community at the neighborhood level.

What Customers Can Expect as Service Resumes in Arizona

Eligible West Valley residents should expect service to gradually resume, with additional preflight checks seeking to help identify temporary hazards. Drone drops are intended for small, low-weight items and take place within the same-day facility network; availability varies by SKU, weather and airspace conditions.

Service might be spotty during high winds, extreme heat or when construction work creates temporary no-go zones. In those cases, orders generally revert to vans or normal delivery. Amazon has said its goal is to make aircraft operations as inconspicuous as possible to the neighborhood while striking a conservative stance on safety.

The Regulatory Road Ahead for Routine BVLOS Drone Flights

The FAA is still in the process of formulating national rules around routine beyond visual line of sight flights, which are an essential precursor to dense urban coverage. Efforts such as BEYOND and NASA’s UTM research have driven the bar higher in terms of technical requirements for remote identification, deconfliction and command-and-control reliability. However, a common BVLOS framework has not yet fully crystallized.

One of the lessons from the Arizona crash is that we need better data on temporary obstacles. A better pipeline — from building permits and crane operators into digital maps that drones consult in real time as they fly — would help minimize surprises. Until such systems are widespread, operators will depend on a stack of mitigations: smarter perception; stricter preflight surveys of flight paths, relying on digital tools based on improved artificial intelligence; and closer coordination between ground control stations.

A cautious restart is a strategic imperative for Amazon. The pledge of Prime Air to reduce delivery times and vehicle miles only pays off at scale, and scale comes from turning incidents into improvements. How well the company rolls out these new protections — and how openly it tackles regulators’ and cities’ concerns — will determine the pace of its next growth spurt.