Mark Zuckerberg’s bungled attempt to accept a WhatsApp call with Meta’s Ray‑Ban Display glasses made for some viral secondhand embarrassment.

The ringtone sounded, the command failed to land, and the moment lingered. But as onstage tech cringes go, this one does not make the all‑time leaderboard — and it can be understood more as an element of the endemic fragility of live demos, wearables, and voice AI than anything about where the product is headed.

What went really wrong — and why that matters

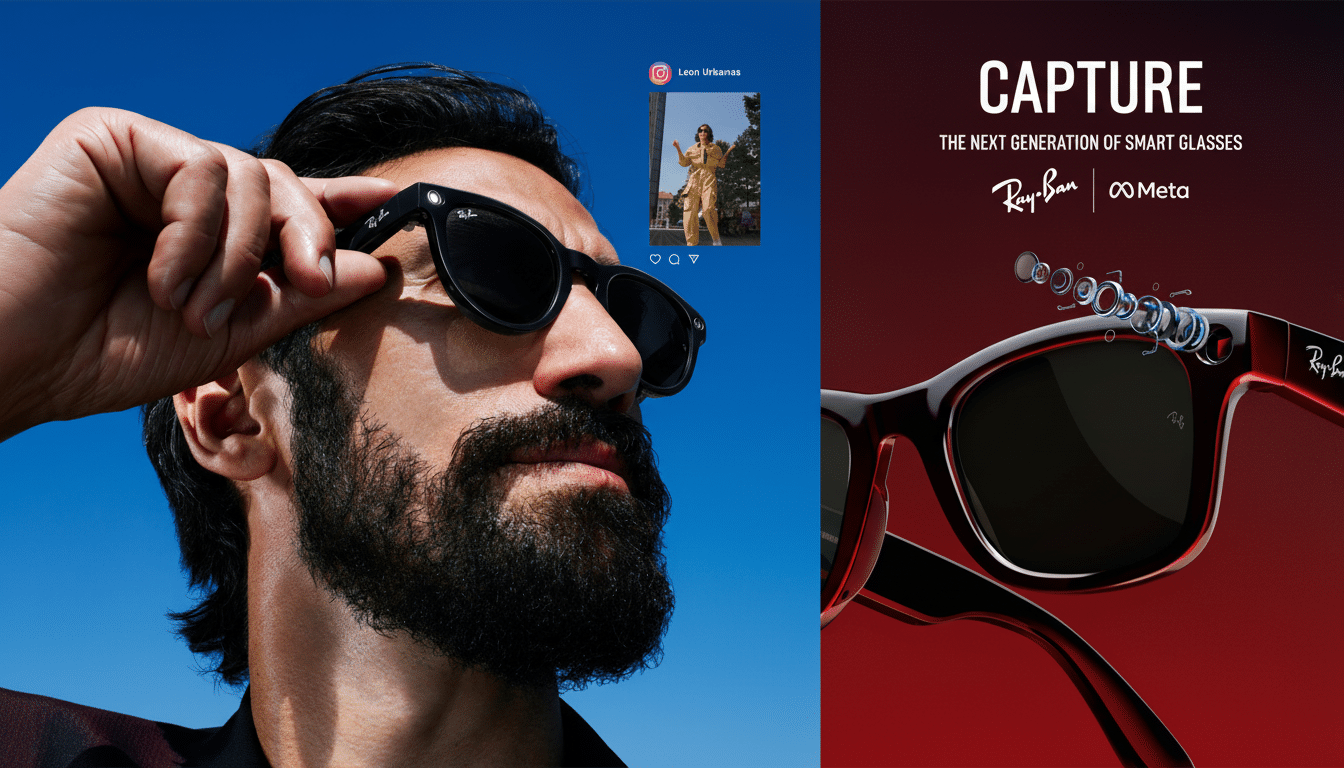

Glasses, like Meta’s Ray‑Ban Display, rely on a fragile chain: Bluetooth and Wi‑Fi connections to your phone; app permissions; voice wake words; far‑field microphones or processors embedded in the glasses (which need instructions of their own); and on‑device or cloud‑stored AI to interpret the command — all inside a crowded room brimming with RF energy.

Any one hop that is misbehaving and you’re in trouble. That’s not a justification; it is the systems reality of hands‑free computing.

Keynotes are the worst‑case environment for live. Tight event Wi‑Fi, hundreds of hotspots, metal staging, broadcasting gear, and sounds over 80 dB in the crowd can plummet ASR accuracy and Bluetooth stability. It’s well‑documented that academic benchmarks for things like the CHiME challenge consistently demonstrate speech models’ error rates skyrocket in the presence of real‑world noise. Even a lone mistimed permission prompt on the paired phone can snowball into dead air onstage.

The larger issue is product dependability outside the ballroom. For Meta’s smart‑glasses effort, the arc is mixed but upward. Initial retention for the first‑gen Ray‑Ban Stories was so low, according to The Information, that sustained usage of a product — post‑purchase — was majority less. The second‑gen push brought with it better cameras, hands‑free capture, and a beefier Meta AI — precisely the kind of functions that, once settled in place, transform things only occasionally called for into daily attire.

For context, a short history of demo disasters

There’s a venerable tradition of tech whiffs that are far messier than a missed call. Think back to Steve Jobs beseeching a roomful of reporters to turn off Wi‑Fi for Safari to load during the iPhone 4 announcement; suddenly, the consummate showman was doing network triage partway through his presentation. It was brutal — and formative for event crews everywhere.

Or in the Microsoft pantheon: the Windows 98 “blue screen of death” occurring as Bill Gates looked on at a PC crashing, later followed by Windows chief Steven Sinofsky’s Surface tablet freezing mid‑demo, requiring him to try to, well, physically turn it away. Those moments didn’t just pause one feature; they undercut confidence in entire platforms.

Then there’s spectacle. Tesla’s Cybertruck window “unbreakable glass” broke — twice — transforming a strength boast into a meme in mere moments. And in the world of AI, Google’s Bard flubbed a fact about the James Webb Space Telescope during its first public demo; per Reuters, it caused the Alphabet Co.’s market value to sink by tens of billions as investors worried over its level of readiness. A recalcitrant WhatsApp reply command, by contrast, is a flesh wound.

Why smart‑glasses demos are unusually fragile

Glasses fall at the nexus of three fragile planes: human, noise, and invisible.

Far‑field microphones have to discern one voice in a crowd; tiny antennas must hold signal near concert‑grade audio rigs; the AI has to understand intent with no delay and slice it into apps amid permissions and APIs that change beneath it. Users forgive a phone tap. They don’t excuse glasses that fumble the easy, low‑friction stuff like answering a call.

That’s particularly pertinent in a category still trying to find its footing. IDC estimates that combined AR/VR shipments are still in single‑digit millions on an annual basis, with actual AR glasses reaching just a tiny slice of that pie. For wearables to become mainstream, reliability needs to be mundane. A product has to succeed at the unglamorous basics — call control, notifications, capturing — before prancingly colorful overlays or multimodal AIs matter.

The reputational math: sting today, little scar tomorrow

Do these moments hurt? In the short term, yes: they’re grist for narratives about vaporware and overpromising. But the results depend, over time, on post‑demo momentum. “Antennagate” was a nonissue once the iPhone experience bounced back. Tesla’s window mishap didn’t deter preorders. A keynote address may be the most anticipated and consequential of all five acts; for Meta, the number to watch is not applause at a keynote — but daily actives, repeat usage from those who own one.

Bottom line: a stumble today, not a product death knell

Zuckerberg’s Ray‑Ban Display misfire will be a meme, but it is not the most crushing one we’ve witnessed, nor is it a verdict on whether the product has potential.

They talk about specs that vanish into everyday life and, yes, the screens of Tomorrowland. Because the path there lies through unerring dependability on the basics. Nail those, and nobody will remember the ringtone that wouldn’t end.