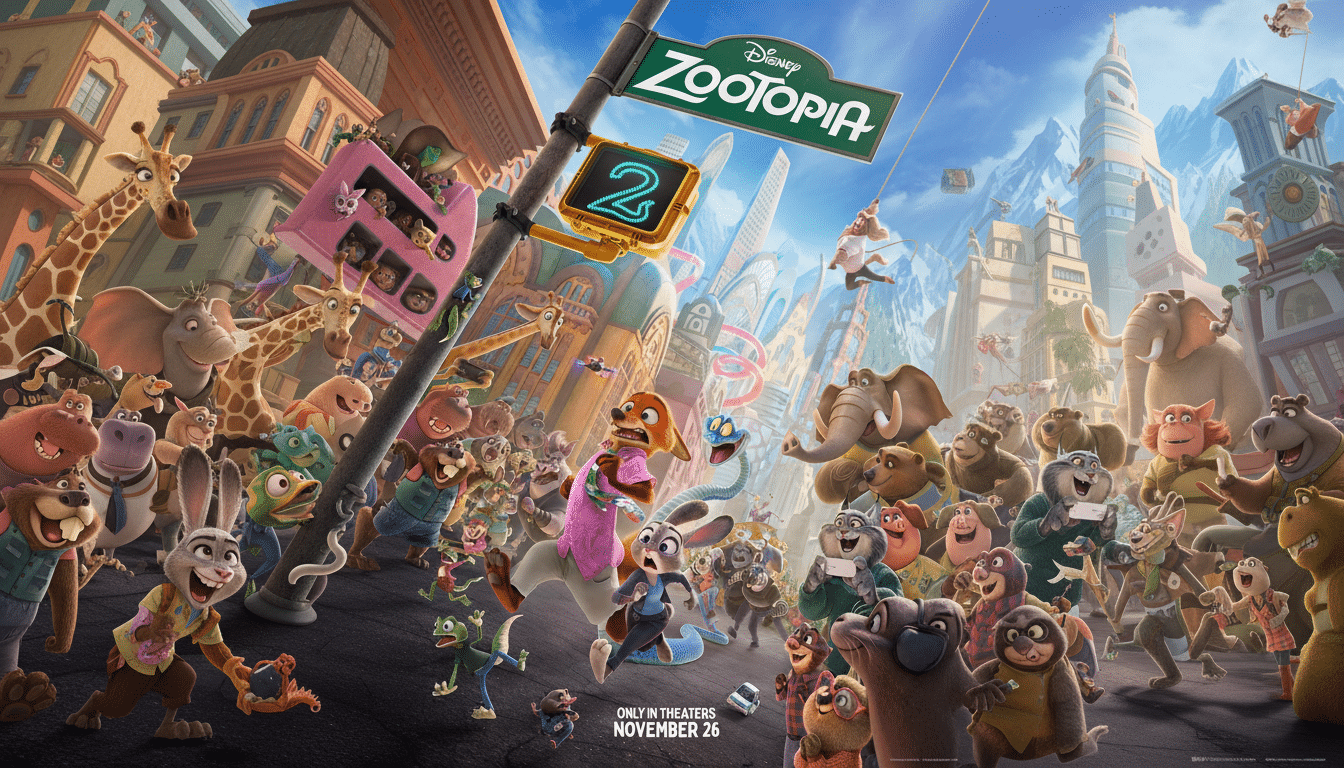

Disney’s least likely civics lesson comes in a fizzy, four-quadrant package. Zootopia 2 pushes the original film’s playful allegory about prejudice and fast-darts its way into the thornier realm of prejudicial urban planning — remapping its animal metropolis to reveal how bias is not only sewn into hearts but also etched onto streets, neighborhoods, territories.

The surprise isn’t that this sequel is funny and fleet; it is. The surprise, it turns out, is that it has the audacity to imagine structural inequality in a world of slick fur and sight gags — and that it extends the themes of its 2016 predecessor (which became a $1 billion movie) into an even more systemic register.

A Buddy-Cop Sequel With A City Planning Plot

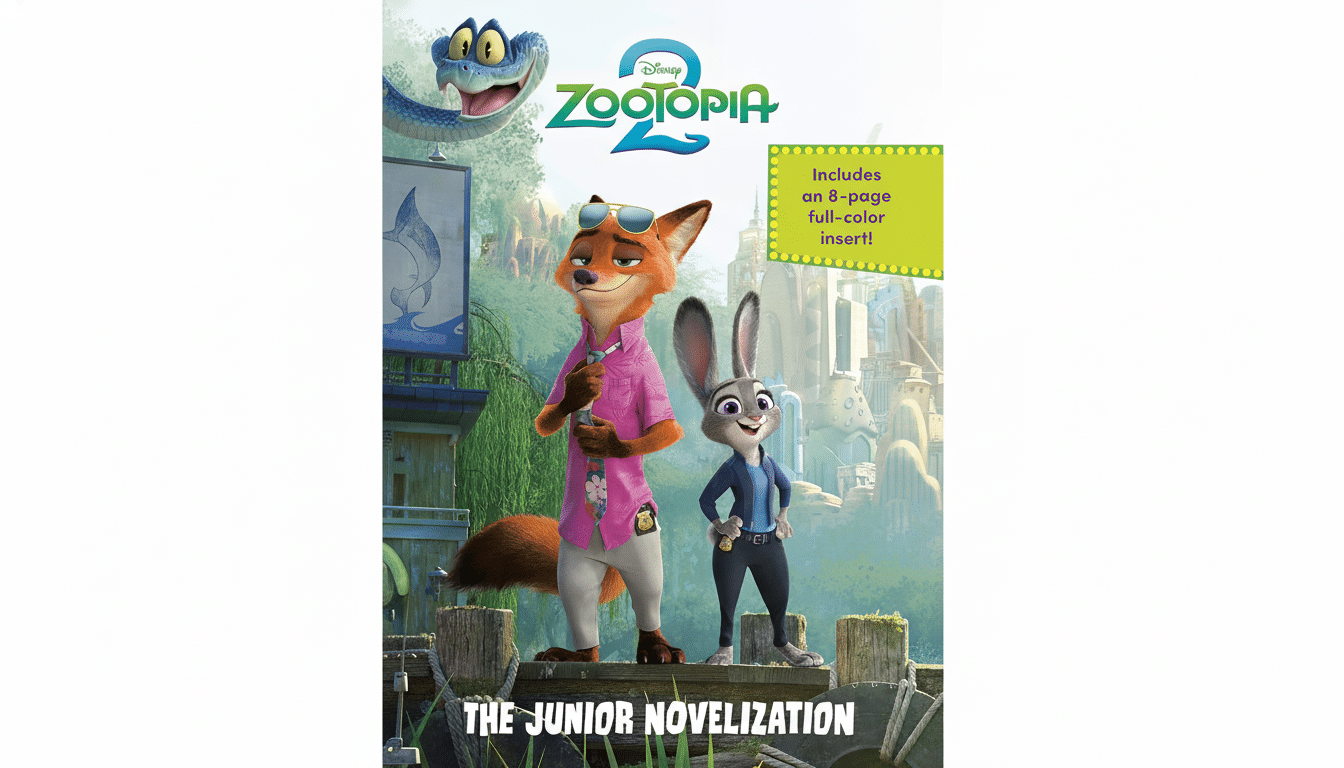

Reunited as ZPD partners and possibly famous, Judy Hopps (Goodwin) and Nick Wilde (Bateman), sidelined after a bust goes poof with a pizza-shaped cloud of smoke, are pushed into a partners’ therapy regimen that exploits their differences for both laughs and character development. The actual engine, however, is a runaway suitcase containing a slithery new character: Gary De’Snake (voiced with breezy charm by Ke Huy Quan), who swipes the journal of the founder of the elite Lynxley clan.

The pursuit reveals a concealed door. Zootopia, once portrayed as an all-mammalian melting pot, is shown to have walled-off neighborhoods — most notably Marsh Market, a home of reptiles and aquatic mammals that was carved out of the city’s big tent when it was founded. That’s not worldbuilding garnish; that is the plot.

From Allegory To Infrastructure In Zootopia 2

Evoking the specter of segregated neighborhoods, the film nods to actual histories. Listeners will hear echoes of the Robert Moses era, with its “slum clearance,” of New York’s Seneca Village razed to build Central Park and highway projects that sliced through neighborhoods from St. Paul to Miami. Urban scholars have long demonstrated how policy decisions solidify social biases into physical place; the movie makes that abstract concept feel concrete and readable to families.

Milton Lynxley (a silkily menacing David Strathairn) is pushing a Tundratown expansion trumpeted as progress. Those who pay, the film suggests, are those who have always paid — residents of districts drawn to be out of sight and out of power. It’s gentrification-as-snowplow, and the metaphor bites in a surprising way.

Worldbuilding With Teeth And Real Urban Stakes

Directors Byron Howard and Jared Bush go surprisingly heavy on geography as character. Thermal zones serve dually as cultural boundaries; transit deserts signal a lapse in the government mail system; raised viaducts create literal shade over the disenfranchised. The craft is clean; the writing readable; and Marsh Market reads like a space with a past — lively, pragmatic-scrounging but still confined by decisions its citizens didn’t make.

The humor still pops. Fortune Feimster’s beaver conspiracy theorist Nibbles Maplestick injects buoyancy, and Shakira’s Gazelle re-enters with a showstopper that helps to keep the tonal balance on the lighter side of things. Goodwin and Bateman are still an all-time odd couple, pairing her caffeinated idealism, his droll defensiveness. Through Gary’s swagger, Quan weaves Hergé with empathy — driving the story toward allyship rather than saviorism.

How Far The Message Spreads Beyond The Chase

No, Judy doesn’t lecture about redlining. Instead, the film turns to capers rather than case law, resorting to group therapy sessions, near-misses and jailbreaks to keep children engaged while sneaking them the idea that systems — not just slurs — make lives too. Most of that balance works, though a few beats are obviously echoing the first movie’s arc of “see the bias, fix the bias.”

What’s new is the frame: discrimination as a map problem. That’s a heavy lift for a studio tentpole, and it offers post-movie chatter without weighing down the story.

The Real-World Resonance Of Zootopia 2 Themes

Urban research from places like the Urban Institute and Brookings has detailed how city after U.S. city sees large shares — commonly north of 70% — of its residential space restricted to single-family zoning, curtailing integration and affordability. The U.S. Department of Transportation has a Reconnecting Communities program that is providing funding for efforts to mend the scars opened by midcentury highways, and projects are also moving forward in places like Syracuse’s I-81 corridor and Detroit’s I-375. UN-Habitat has also pushed for planners that are inclusive and human-scale in a way that avoids replicating the harms of 20th-century trends.

Zootopia 2 doesn’t care to namecheck any of that, but it does rhyme with its moment. By using a kids’ chase movie as the framework for a parable about who gets a seat at the table — or, really, who gets stairs and even a front door — it taps into live debates over zoning reform, displacement and just who cities are for.

Verdict: A Sharp, Civic-Minded Sequel That Delivers

Subverting without shouting, the sequel opens out the franchise’s moral horizon from interpersonal to infrastructural. Some narrative déjà vu aside, this is robust, generous popular entertainment with an unusually pointed civic conscience. It entertains first, then lodges a question that doesn’t go away: if a flower-of-reconciliation city left whole neighborhoods lying beyond its pale, what does that say about ours?