Zanskar, a geothermal exploration startup, argues that the world is missing a terawatt-scale opportunity hiding in plain sight. While policy roadmaps often lean on next-generation enhanced geothermal systems (EGS), the company says conventional hydrothermal resources—long considered picked over—could deliver vastly more power than widely assumed if modern exploration, drilling, and data science are applied at scale.

Conventional Geothermal Makes A Comeback

The U.S. Department of Energy’s GeoVision analysis projects around 60 gigawatts of geothermal capacity by mid-century, a figure frequently framed as approaching a tenth of U.S. electricity supply by 2050. Much of that hinges on EGS, which uses oil-and-gas-style stimulation to turn hot dry rock into a reservoir. Companies like Fervo and Sage Geosystems have pushed EGS forward, with field demonstrations showing promising flow rates and grid injections.

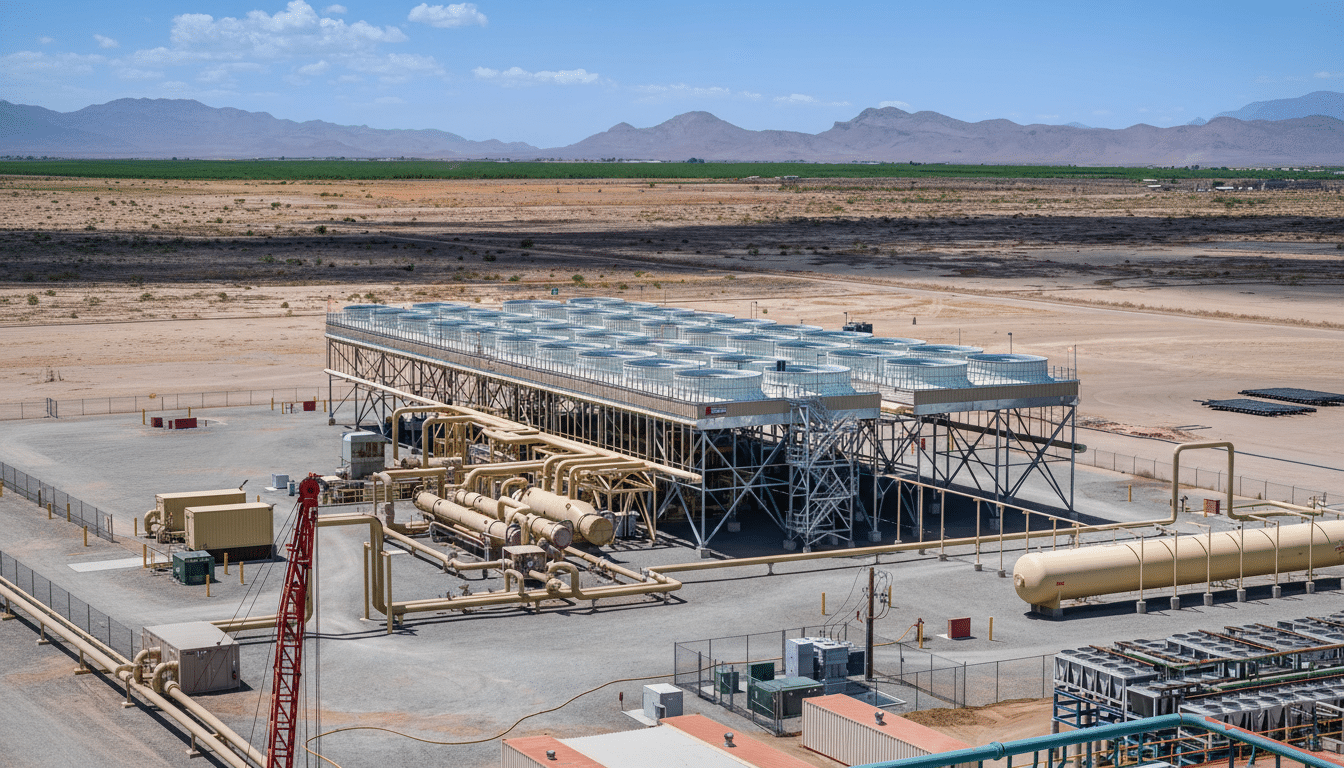

Conventional geothermal—drawing heat and fluids from naturally permeable reservoirs—has stagnated, with roughly 4 gigawatts installed in the U.S. after years of inching growth. Zanskar contends that plateau reflects a search problem, not a resource limit. The company points to a persistent bias toward surface “tells” such as hot springs and fumaroles. Internal analyses suggest most viable systems—on the order of 95%—lack obvious surface expression, meaning they are easy to miss without deeper probabilistic mapping.

AI Hunts Hidden Hydrothermal Systems at Scale

Zanskar’s workflow starts with supervised machine learning trained on decades of public and proprietary data: accidental discoveries, well logs, gravity and magnetotelluric surveys, heat flow maps, seismicity, and structural geology. Candidate zones then move to a decision framework rooted in Bayesian evidential learning. Instead of leaning on a single best-fit model, the system constructs priors from available evidence, actively tries to falsify competing hypotheses, and quantifies the remaining uncertainty. Where data are sparse, a custom geothermal simulator helps bound likely reservoir geometries and temperatures.

The company says the approach has already delivered: it helped restore output at an underperforming plant in New Mexico and surfaced two new prospects with a combined potential exceeding 100 megawatts. Those early wins, Zanskar argues, validate a repeatable playbook—screen many basins cheaply, concentrate expensive fieldwork only where probabilities stack up, and iterate as new measurements arrive.

How the Math Reaches 1 TW of Geothermal Capacity

Reaching terawatt-scale sounds audacious until you consider two multipliers: count and productivity. The U.S. Geological Survey’s prior assessments have suggested tens of gigawatts of undiscovered hydrothermal potential in the U.S. alone, and those estimates predate today’s data density and drilling tools. If overlooked systems worldwide number an order of magnitude higher than cataloged fields, and if better well placement, deviated drilling, and reservoir management can lift recoverable energy per field by another order of magnitude, the aggregate climbs rapidly into the terawatt range.

Capacity factor matters, too. Geothermal routinely delivers 70–90% capacity factors, making each installed megawatt disproportionately valuable for firm, carbon-free supply compared with intermittent resources. Lazard’s recent levelized cost estimates place new geothermal broadly in the $60–$110/MWh range, with costs falling as exploration risk declines and project financing replaces venture dollars. If Zanskar’s methods cut dry-hole rates and shave 10–20% off drilling and testing outlays, the economics improve quickly.

Funding To Bridge From Pilot To Project Finance

To scale the search, Zanskar closed a $115 million Series C led by Spring Lane Capital, with participation from climate and industrial investors including Lowercarbon Capital, Munich Re Ventures, Obvious Ventures, Union Square Ventures, and others. The company says its current pipeline can support at least 1 gigawatt of capacity, concentrated in the U.S. West where high heat flow and transmission access overlap.

The near-term goal is to advance 10 or more confirmed sites far enough to unlock non-recourse project finance and insurance, pushing down the cost of capital. That shift is crucial for geothermal, where upfront drilling risk historically stranded projects in the “valley of death.” Having risk-savvy backers—reinsurers, infrastructure funds, and strategics—signals growing comfort with underwriting subsurface uncertainty when supported by robust probability models.

Constraints Still Apply to Geothermal Expansion Plans

None of this eliminates classic bottlenecks: permitting for drilling and transmission, water management, induced seismicity safeguards, interconnection queues, and the practical limits of rig availability. The International Energy Agency has repeatedly noted that permitting timelines can erase otherwise compelling geothermal economics. Zanskar’s bet is that sharper targeting reduces the number of wells and surveys needed per successful field, compressing timelines and freeing rigs for the next site.

EGS is not sidelined, either. In a plausible future, conventional hydrothermal sites deliver bankable baseload today, while EGS expands the addressable heat resource dramatically over the next decade. If both advance, the grid gets firm power diversity—and a better chance of hitting clean energy goals without overbuilding storage.

The Signal to Watch for Zanskar’s Geothermal Thesis

The clearest indicator that Zanskar’s thesis is real will be a string of producing projects that meet or beat pre-drill expectations on flow, temperature, and cost. Hit rate, not headlines, will decide whether conventional geothermal has been underestimated. If the company’s discovery engine keeps delivering, the market may have to redraw the geothermal map—from a handful of obvious hotspots to a broad portfolio of quiet, high-value reservoirs hiding in the data.