The AI startup co-founded by Fei-Fei Li has released Marble, a business world model that transforms text prompts, images, video clips, 3D scenes, and panoramas into an editable 3D environment.

Delivered in freemium and paid options, Marble shifts the battle for spatially intelligent AI out of research demos to production-ready workflows.

- What Marble Does Differently from Other World Generators

- Tools for Creative Control in Building 3D Environments

- Pricing and Access Options for Marble’s World Model

- Where Marble Fits in the Fast-Moving World Model Race

- Early Use Cases for Marble in Games, VFX, and VR

- Journey to Spatial Intelligence and Robotics

What Marble Does Differently from Other World Generators

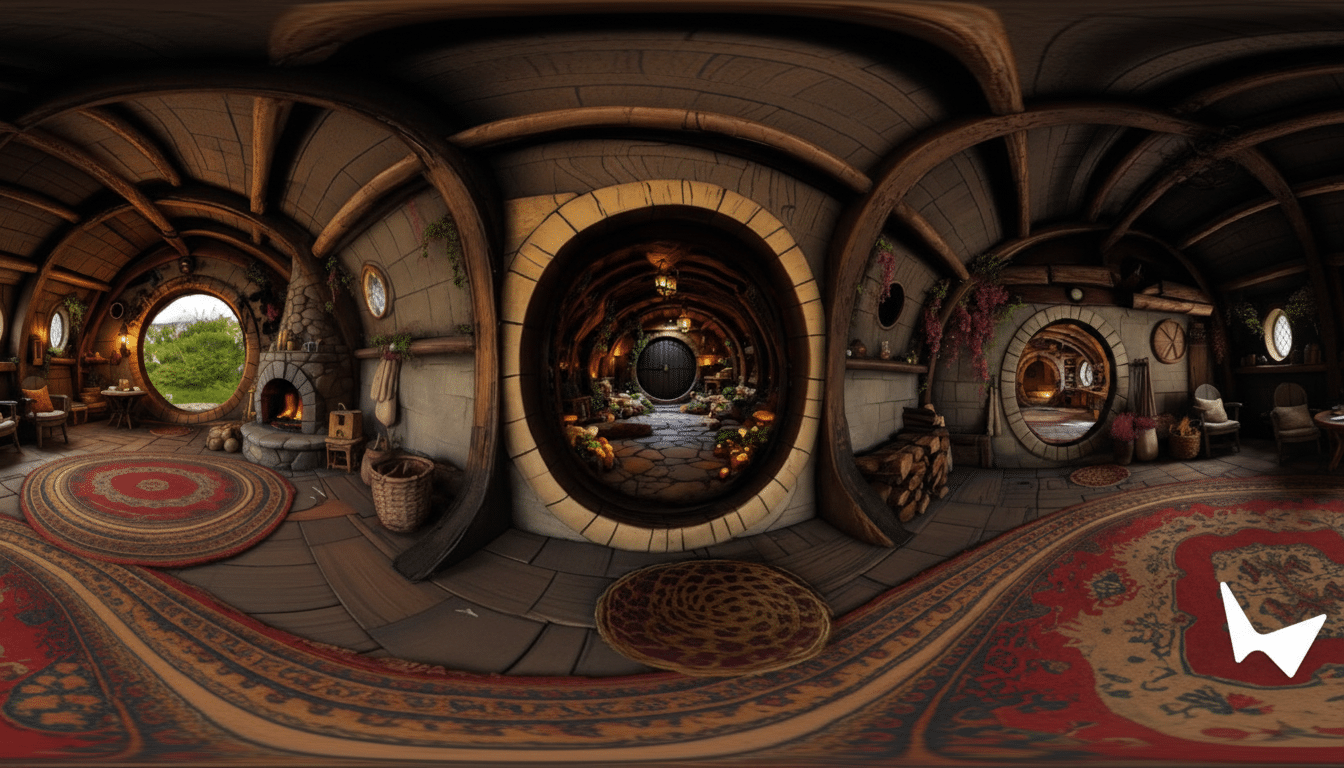

Unlike other on-the-fly world generators that transform as users move about, Marble delivers downloadable scenes with persistence across views. Users can export assets as Gaussian splats, meshes or rendered video — a level of determinism that most AI-generated videos and images find hard to match. This move from ephemeral to intelligent environments is important when considering game, VFX and simulation pipelines that require reproducibility, versioning, and hand-off across teams.

The launch comes after a restricted beta period and just over a year since World Labs came out of stealth with $230 million in investment. It also complements the company’s real-time model RTFM, but Marble is the first to place asset-grade outputs front and centre. Rivals among startups — like Decart and Odyssey — have free demos, and Google’s Genie is still in research preview; Marble is marketing itself as a tool that can be used today for commercial projects.

Tools for Creative Control in Building 3D Environments

Marble knuckles down on control — an area where creative teams can often feel generative tools shortchange them. Its 3D editor is hybrid, allowing users to sketch spatial structure first, and then style it with prompts — essentially divorcing layout from appearance. World Labs’ experimental Chisel interface takes this further: creators can block out walls, planes and objects, then tweak by dragging or scaling geometry directly before Marble fills in photorealistic details.

Two other qualities pertain to production requirements. Scene expansion allows users to grow a created world further — helpful when the edges begin to thin, or when there needs to be one more hallway just off camera for movement. Thanks to composer mode, you can stitch multiple AI-made spaces into a larger whole, meaning that instead of rebuilding and starting over it becomes modular.

Input flex has also been improved since beta. Along with single images, creators can upload multi-angle photos or short snippets of film, all contributing to help Marble build more accurate digital twins of physical space — one of the most common constraints for teams prototyping levels or previsualization shots on a tight timeline.

Pricing and Access Options for Marble’s World Model

Marble is now offering four tiers: Free (four generations from text, image or panorama input), Standard for $20 per month (12 generations with multi-image or video input and advanced editing features), Pro for $35 per month (25 generations with scene expansion and commercial rights) and Max for $95 per month (75 generations of “hyper-realistic” output as well as full feature access). The company sees Pro and Max as a sweet spot for indie studios and VFX teams that require licensed outputs and iteration headroom.

Where Marble Fits in the Fast-Moving World Model Race

World models try to internalize physics, layout and affordances so that systems can predict what will happen as a result of doing something and plan accordingly. Marble focuses less on agentic planning, and more on spatially manageable, editable assets. That keeps it aligned with the research directions of Genie and other simulators while being practical for authors who need files they can open tomorrow in standard tools.

Exporting to formats such as Gaussian splats and meshes makes integration into engines like Unity, Unreal Engine or DCC tools for film easy. In sum: Marble turns a decades-old research milestone — the ability to hallucinate a navigable 3D world — into things that can exist in real production schedules.

Early Use Cases for Marble in Games, VFX, and VR

Game makers will probably, in other words, deploy Marble for static landscapes and ambient spaces or as a previsualization tool and then run interactivity, logic and code inside more standard engines. The Game Developers Conference’s State of the Industry survey, for example, recently revealed that about one-third of respondents considered generative AI to be a force for good in gaming — but also nearly a third worked at companies which experienced the opposite (12% higher than last year) and listed IP risks, quality concerns and power consumption as their reasons. Marble’s controllability and transparent export route will be put to the test by those fears.

For VFX, Marble cuts through the usual morass of faux-AI video issues — jittering, warping, bad camera control — by allowing artists to place cameras inside and around stable 3D environments as well as author frame-accurate moves. On the immersive side, the demand for content is there and growing; Marble worlds can already be seen on Vision Pro and Quest 3 — a pragmatic bridge before we have native VR pipelines.

Journey to Spatial Intelligence and Robotics

Fei-Fei Li has said for some time that machines need spatial intelligence to make sense of the physical world. Marble is among the early moves: not just creating images, but capturing relationships across all of these objects so that it can negotiate what’s where, and how things fit together. That substrate might help robotics training, where data is a scarce resource and simulated environments are valuable for rapid iteration and safety testing, a complaint I hear from labs across academia and industry.

Open questions remain — over content provenance, licensing and bias in training data, for example. But in delivering persistent worlds, AI-native editing, and a clear pipeline into the standard tools out there in the real world, World Labs has made this kind of model less of a thing you chat about in speculative demos and more of something that can be landed on as a production choice. If language models taught machines to read and write, Marble proposes the next act is teaching them to see, stage and construct.