Wi-Fi standards are the rulebook that makes the wireless logo on the back of your phone, router, laptop and, of course, smart home gadgets work. They dictate how devices speak over the air, on what frequencies and how efficiently they share the channel. A comprehension of the differences between them can help you choose the appropriate router, diagnose slowdowns and make upgrades that actually work.

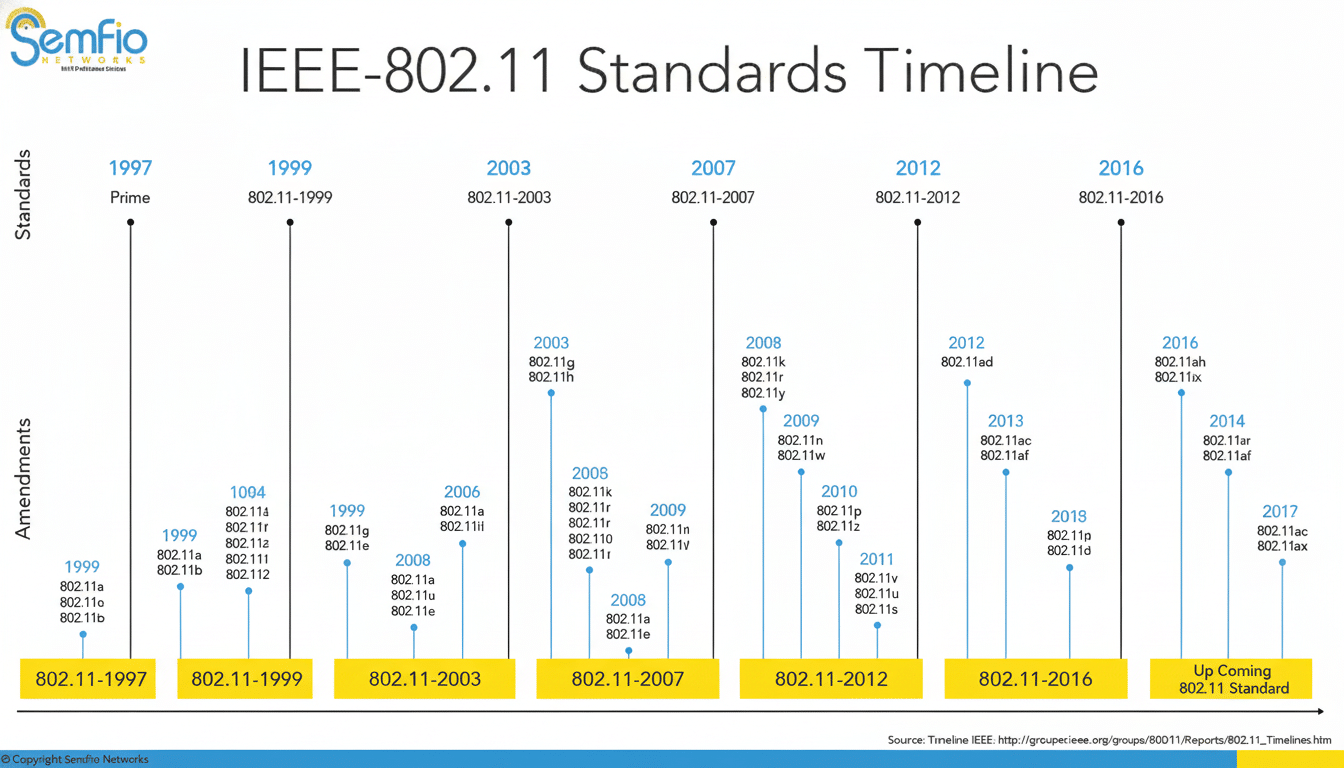

Under the hood, each generation in the IEEE 802.11 family slightly differentiates how spectrum is used, as well as channel width, modulation, and antenna strategies to find the best compromise between speed, range, and reliability. The gear is then certified by the Wi-Fi Alliance as interoperable and assigned consumer-friendly names — Wi-Fi 4, 5, 6, 6E and 7.

What “Wi‑Fi standards” actually are

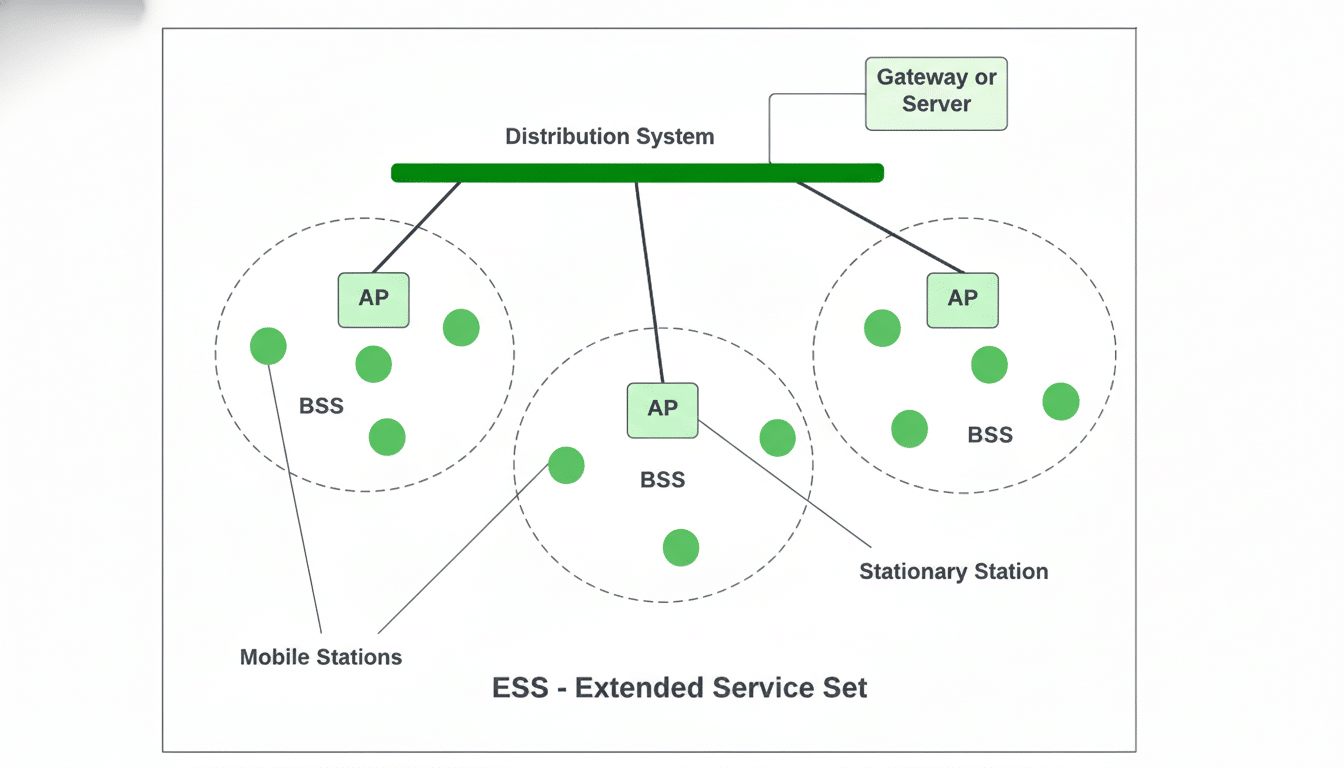

IEEE 802.11 specifies PHY and MAC for Wi-Fi. That includes how bits are modulated in radio waves, how devices share the airwaves and how multiple antennas are used to increase capacity. Newer add-ons extend capabilities while being backward compatible so old clients can still connect.

Certification matters. The Wi-Fi Alliance conducts conformance tests, brands features (such as Wi‑Fi CERTIFIED 6E), and verifies security, such as WPA3. Regulators shape performance, too: in the U.S., the F.C.C. has unlocked 1,200 MHz of new spectrum at 6 GHz, and European regulators have approved 500 MHz of spectrum. And those decisions have direct impact on congestion, channel sizes and actual world speed.

Bands, channels, and physics

2.4 GHz travels farther and through walls, but is crowded and slow. In most places, the 2.4 GHz range is limited to three non-overlapping 20 MHz channels, and is susceptible to interference from neighbors and electronic devices like microwaves and Bluetooth. It’s what you want for long-range sensors, not for high-bitrate streaming.

5 GHz is far more flexible in channels and breadth (40/80/160 MHz), which allows for much higher throughput. The tradeoff is range: Higher frequencies are attenuated more with brick and concrete. Some channels are below DFS rules to dodge radar interference that could cause a router to switch channels in progress.

6 GHz, the band introduced with Wi‑Fi 6E, is the clearest neighborhood — no legacy clients and plenty of room for low-latency links. It works best in the same room, or near line of sight. You’ll see shorter range than 5 GHz and region-specific power limits that limit whole-home coverage.

At one extreme, 60 GHz (802.11ad/ay) provides multi‑gigabit links in the same room, with near line‑of‑sight, while sub‑1 GHz (802.11ah, “HaLow”) sacrifices speed for kilometer‑scale range for IoT. They both have niche use cases, not the general at-home networking.

Wi‑Fi 4, Wi‑Fi 5, Wi‑Fi 6/6E, and Wi‑Fi 7 at a glance

MIMO and 40 MHz channels were introduced with Wi‑Fi 4 (802.11n) and peaked at 600 Mb/s across multiple streams. It is still popular in budget gear and IoT devices, since 2.4 GHz modules are inexpensive and good on battery life, but the performance in congested apartments can be spotty.

Wi‑Fi 5 (802.11ac), in dedicated 5 GHz only, with 256‑QAM, 80/160 MHz channels, and downlink MU‑MIMO. In the real world, users often experience 300-800Mb/s even in the same room as an able client — more than enough for gigabit-level broadband when everything is working optimally.

Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax) is as much about performance as it is about a faster sheer speed. It introduces OFDMA to allow multiple small transmissions to be scheduled together, uplink and downlink multiuser MIMO, BSS coloring for mitigating co-channel interference, beamforming and Target Wake Time to improve battery life. Wi‑Fi 6E brings those advantages to 6 GHz, making dozens of new channels available. Wi‑Fi 6/6E now represents the majority of new device shipments, with substantial momentum and rapid adoption across phones and PCs, says the Wi‑Fi Alliance and industry trackers.

Wi‑Fi 7 (802.11be) layers on 320 MHz channels, 4K‑QAM, multi‑link operation (MLO) to bond bands together, and more flexible resource units. The headline PHY rate can reach over 40 Gb/s on paper over many streams; single-device peaks of 2–5 Gb/s may be achievable under highly optimized conditions. The Wi‑Fi Alliance’s Wi‑Fi CERTIFIED 7 program solidifies interoperability, but early routers come with a price premium, and a majority of clients are still maxing out at Wi‑Fi 6/6E.

Special-purpose standards you might hear about

802.11ah (HaLow) This standard works sub 1 GHz with tiny channels to achieve range and battery life for sensors, agriculture and industrial controls. Its speed is humble, but it can blanket a factory or a field where conventional Wi‑Fi encounters trouble.

Both of 802.11ad and 802.11ay use 60 GHz to provide ultra‑wide channels and very low latency. These things work well for wireless VR headsets, docking stations and small point‑to‑point links, but walls and occasionally just people can interrupt the signal, making them unappealing to a broader audience.

How to pick — and what really matters

Choose the standard that best fits your configuration and service. If your broadband is pushing the upper limit of near 500 Mb/s, a good Wi‑Fi 6 setup might provide equivalent performance to an expensive Wi‑Fi 7 kit. In other words, a Wi‑Fi 6/6E mesh system with Ethernet backhaul will serve big multistory homes much better than a single ultra‑fast router.

Reserve 6 GHz for same‑room workstations and consoles, 5 GHz for most rooms, and 2.4 GHz for far‑flung sensors and smart plugs. Broader channels (160/320 MHz) increase peak speed but are more susceptible to interference; in crowded areas, narrower channels generally result in steadier performance.

Finally, clients drive the experience. A Wi‑Fi 7 router is unable to deliver a Wi‑Fi 5 phone with multi‑gigabit rates. So look out for WPA3 security, OFDMA and MU‑MIMO support on both sides, and also check local regulations issued by regulators such as the FCC or Ofcom when it comes to channel availability and power limits that affect coverage.