ChatGPT’s voice mode is remarkably quick, friendly, and uncanny. It is also, too often, wrong. If you value accuracy of information or sophisticated reasoning, the voice interface consistently lags behind the web chat. The model isn’t the problem; it’s how human conversation in real time is guided. The latency targets the system toward a rate or volume of speech, crowding out the “thinking time” textual chats tend to take for the consideration, testing, and revision of ideas.

Speed-first design reduces deliberation and accuracy

For real-time voice assistants, it’s the responsiveness that makes or breaks such experiences. Interaction-design research from the Nielsen Norman Group finds that “one second is about right for users’ flow of thought to stay uninterrupted, even though the user will notice the delay. Ten seconds feels like an eternity.” By the way, a response time over 300 ms feels sluggish, like a mobile-phone conversation with someone in Iceland. That stream of partial responses is what voice systems use to reach that eight-second goal. That helps keep the talk going, but it also discourages the model from stopping to plan, search, or verify—processes that frequently improve accuracy in text chat.

- Speed-first design reduces deliberation and accuracy

- Three places where errors commonly creep into voice mode

- Same model, different mode: why results diverge in voice

- Real-world voice misfires that illustrate the core problem

- How to get better answers from voice and text modes

- When voice mode still makes sense—and when it doesn’t

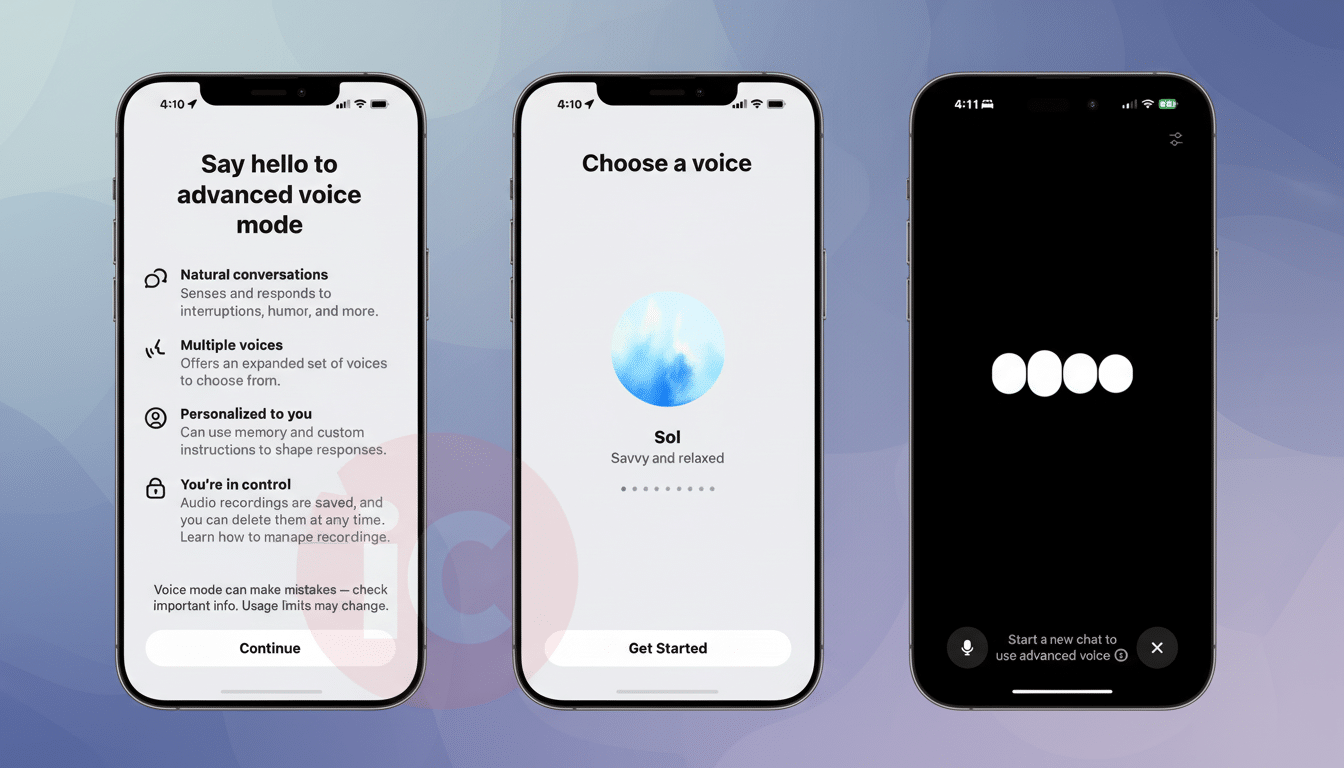

OpenAI’s own product materials state that low-latency, interactive speech is among its close goals for voice. In practice, this translates to fewer chances to call tools, explore, or do extra reasoning passes before answering. The result can be confident-sounding, without the mental backtracking that catches errors.

Three places where errors commonly creep into voice mode

First, speech recognition adds noise. Even high-quality automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems can mishear brand names, model numbers, or proper nouns—precisely the information needed to determine whether an answer is correct. NIST tests have consistently revealed that word error rates increase for spontaneous, accented, or noisy speech, such as in the case of real conversations.

Second, the streaming generation requires early commitment. Because the model starts speaking before it can reach a complete shape of an answer, it runs the risk of locking into the wrong path and then “rationalizing” it. So, our picture might look too pleasant: Neither of these papers seems to measure how much hallucination spreads when being forced by algorithms not to verify (which we suspect will be roughly accepted conditional-ness times iterations), except the “admitted hallucinations” score they both compute as relatively low; it was also found elsewhere that what increases confabulations is low-latency decoding and high-middle variability settings.

Third, context is thinner. A voice session typically has less on-screen memory and disables some tools compared with the web interface. If retrieval, code execution, and browsing all take longer to initiate—or there is less access—the model starts relying more on past patterns rather than looking up real-time information.

Same model, different mode: why results diverge in voice

Many users are astonished when they discover that the very same underlying model performs well in web chat but underperforms in voice. The discrepancy has to do with interaction restrictions. You can ask in text for a moment to “think it through,” and have the system take a longer internal pass before coming to rest. In voice, the design leans toward intimacy. The dialogue continues to evolve—even when the response has yet to catch up.

There’s also a personalization gap. Some users claim that in standard voice sessions their wishes are taken into account more than in advanced voice modes, where they are sometimes not even heeded. It’s a mismatch that can nudge the assistant into a default persona—chattier, less rigorous—than you may have had in mind. Community threads on r/OpenAI reflect this pattern. The voice responses are shallower and more obstinate than text in response to challenges.

Real-world voice misfires that illustrate the core problem

In side-by-side tests, voice mode has boldly created features for fictional phone hardware, gotten wrong which buttons are part of a popular high-end phone—and blown a basic day-of-the-week riddle in the face of correction. But when users switched to the web interface and, with the same prompt, asked similar questions, they got careful, sourced, and fully consistent answers. The pattern is not only anecdotal: In Reddit threads over several months with complaints of this type, people describe the same thing—curt replies, brittle defensiveness, and less substantive corrections on follow-up.

This gap mirrors broader measurements. In its coverage of the release, the AI Index from Stanford HAI notes that even among leading models hallucinations remain a concern, and error rates range significantly depending on task. Throw in ASR noise, plus streaming pressure, and all those baseline risks are worse off for voice. The actual content sounds a bit more human, but the guardrails that make sure things are reliable are thinner.

How to get better answers from voice and text modes

Save your asks for things that matter—factual information, technical troubleshooting, $1,000 medical or financial questions, and logic puzzles. Ask the system to test an assumption, compare two possibilities, or present sources by name. Prompts that take the form of “pause and check for errors in every step before speaking” are more effective at encouraging conscious reasoning processes in text.

If you have to use voice, make it slow. Try “pause and think before you respond,” followed by a direct call for both an overview and a process-error check. Make your questions short, circumvent jargon that ASR can mutilate, and verify critical nouns or numbers. If the response rings false, shout and make it repeat with sources or entertain the alternative.

When voice mode still makes sense—and when it doesn’t

Voice is great for extemporaneous brainstorming, drafting outlines, or casual Q&A when you need to move more quickly than accurately. It’s excellent for coming up with ideas that you can later develop in text. Only don’t trust it for hard facts or decisions. Use voice output as a first pass, then come to the web chat for verification and polish.

The bottom line is that real-time conversation is a performance trade-off. If getting it right is important, go to text and let the model think and count proof as part of the workflow. Reserve your voice for convenience, not accuracy.