Vermont’s broadband chief, Christine Hallquist, is no satellite skeptic — she uses Starlink herself at home in the woods. Yet when it comes to the limited pool of federal broadband dollars, she said, the wisest bet for taxpayers is fiber. This isn’t about ideology; it’s about math, physics and long-term value.

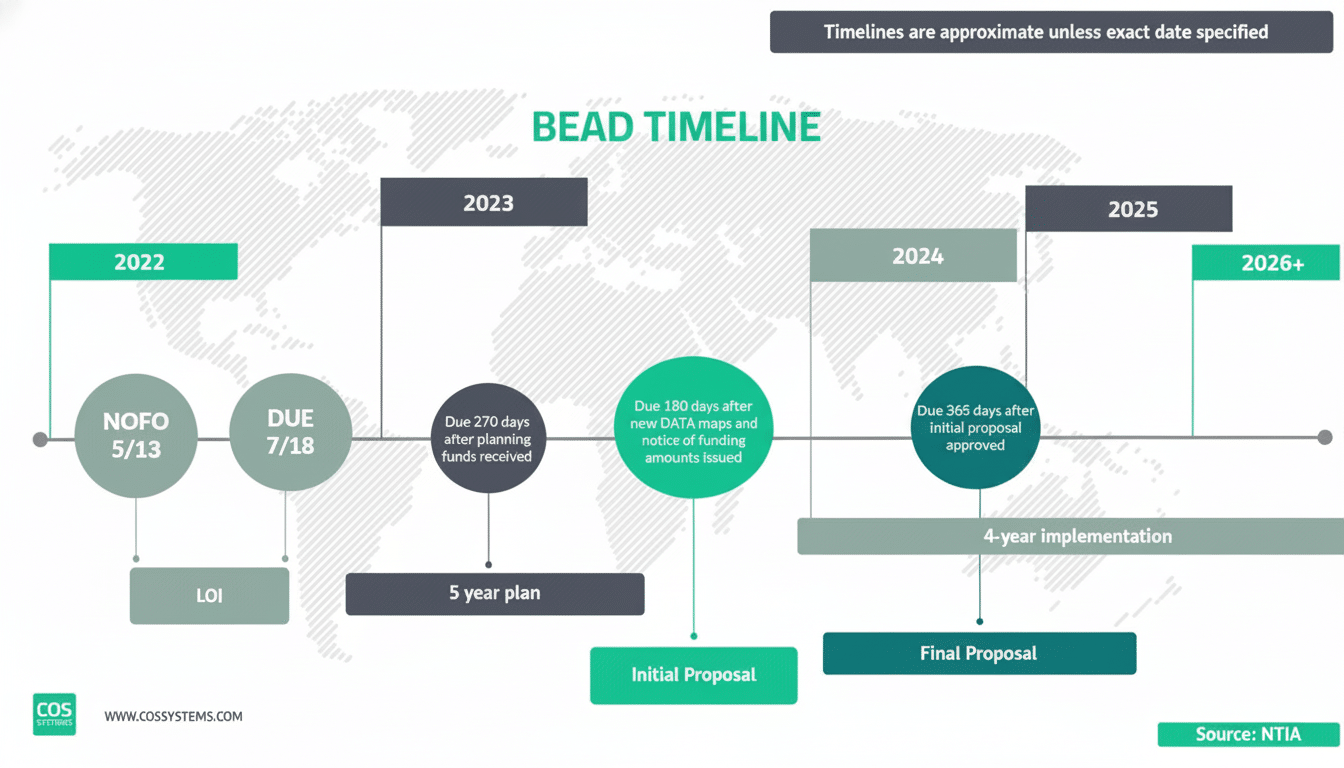

As states decide what to do with Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) funds, Vermont’s plan places fiber in the center and leaves satellites for the few spots where stringing glass just doesn’t make financial sense. SpaceX has countered, calling on states to apply more pressure to Starlink. Vermont has clung to its calculus.

Investment Logic: Comparing Cost Per Gigabit Over Time

Hallquist’s fundamental point is to look at the cost per gigabit delivered and not simply the cost per location. Cost of actual deployment is several thousand dollars per home for fiber in mountainous or difficult terrain compared to the cost of a few hundred dollars to install a Starlink terminal. But monthly performance and capacity turn the ledger over a 10- to 20-year time frame.

Common fiber packages, even in rural builds, offer above-1 Gbps service (symmetrical) for $70-$80 a month. Starlink’s residential tiers typically fall between 100Mbps and 300Mbps, and prices hit around $120. For multiuser households, 4K streaming, cloud backups and remote work, the dollar-per-megabit advantage stacks up in fiber’s favor.

Fiber is the “gold standard” for high-capacity, low-latency service, according to NTIA, which manages BEAD. Vermont’s team subscribes to that view not just in terms of speed, but when it comes to reliability and upgrade headroom as well, since fiber’s economics continue to improve as more traffic rides the same strand.

Capacity, Latency and Vermont’s Tough Terrain

LEO satellites, like Starlink, can provide a low-latency connection that would clear BEAD’s performance rules and are literal lifesavers when roads, ledges, or river crossings make fiber infeasible. But satellites are a shared medium with limited throughput in each beam. As take rates rise in an urban valley or along a rural corridor, peak-hour speeds can sag — a phenomenon reflected in independent speed testing from Ookla, where there’s significant regional variation tied to congestion.

Then there’s Vermont’s canopy. Line-of-sight is problematic due to thick hardwood forests and rugged terrain. Even with purportedly better beam-switching technology that SpaceX has promised, some areas may never achieve reliable service due to terrain and tree canopy, Hallquist warns. Unlike a buried fiber drop, a satellite install is subject to the whims of Jack Frost’s offspring when it comes to foliage and snow load and ice.

A 30- to 50-Year Asset vs. 5-Year Satellites

Fiber is a once-in-a-generation asset. The glass in the ground can last for decades; service providers swap out the electronics at either end to scale from today’s XGS-PON to 25-gigabit or 50-gigabit PON sometime in the future. The Fiber Broadband Association and numerous utility studies also repeatedly note fiber’s low operating costs and upgrade path as reasons it ultimately outperforms.

From the perspective of design, LEO systems are ephemeral. Satellites in orbit need to be replaced after a handful of years, and require a steady launch cadence. That energy and capital expenses to support the constellation are not part of a household’s installation invoice, but they are real. From Hallquist’s perspective, when public dollars pay to build a durable infrastructure that lasts for generations, it is hard for the lifetime cost-per-bit of fiber to be beaten.

Inside Vermont’s BEAD Plan for Broadband Deployment

Vermont’s plan allocates the majority of funds — more than four in five eligible locations — to fiber builds, with a small sliver for satellite in locations where fiber would be cost-prohibitive per location. The state also set an upper cost threshold: if it would cost more to reach a premises than the ceiling, satellite becomes the backstop.

SpaceX has claimed that Vermont is overpaying in some areas and called on federal referees to steer more addresses toward Starlink. Vermont’s response is that fiber will reach more people, do the job better and at lower cost, for decades. The state also assumes that some share of the addresses that these satellites designate won’t be able to connect because of dense tree cover or obstacles related to topography — reminders that satellites aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution.

Hallquist is matter-of-fact about the trade-offs. There is a place for satellite among the mix of those serving Vermont, she said, particularly for isolated homes that are too far out to reach practically with fiber. But in places where fiber can be built responsibly and at a measured cost, it is the “best investment” that rural economies, schools, healthcare providers, and small businesses lacking dependable, scalable bandwidth could have.

Policy Crosscurrents and Industry Pressure

States need NTIA approval for their BEAD plans, and industry interests are lobbying fiercely. SpaceX isn’t alone — Amazon, with its Project Kuiper, is also angling for a piece of the difficult-to-reach places pie. Still, most states are leaning fiber-first, a position that aligns with initial BEAD guidance and experience from earlier programs.

Regulatory history also looms. The FCC rejected Starlink’s application for federally subsidized rural support after the company proposed providing broadband under a program called RDOF, not being satisfied that it could deliver and cover long-term costs — an episode that further instilled caution in many states. And the Pew Charitable Trusts and state broadband offices have also emphasized that future-proof infrastructure ought to be the default when public money is in play.

Why It Matters for Rural Vermont’s Digital Future

This is not a fiber-versus-satellite culture war. It’s a question of what we prioritize: when should taxpayers invest in permanent infrastructure, and when is it more reasonable to buy a service that functions today but may have to be continually replaced? Vermont’s solution is to bring fiber wherever it makes economic sense and employ satellites as a targeted tool, not an indiscriminate replacement.

For rural Vermonters, the stakes are concrete — classrooms migrating online, telehealth becoming routine and local businesses selling to the world. Hallquist’s gamble is that a strand of glass to the doorstep will return dividends long beyond the last BEAD dollar. Satellite offers a bridge across gaps — fiber, she says, makes futures.