In the comfortable atmosphere of Earth, we take for granted that two pieces of metal will remain separate. If you stack two clean sheets of aluminum on top of each other, they don’t become one block. You can pick the top one up.

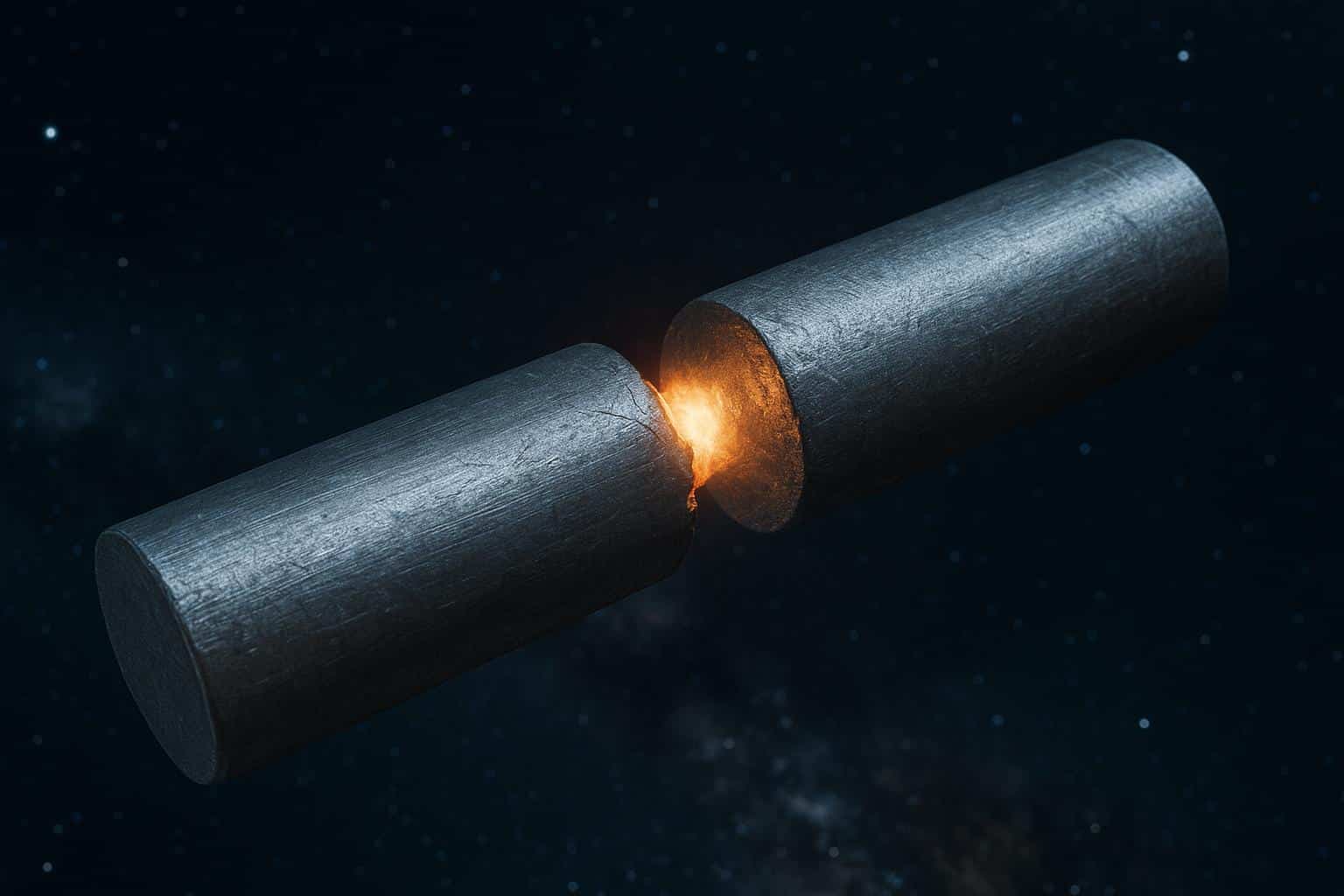

But if you took those same two sheets of aluminum into the vacuum of space and touched them together, something terrifying would happen. They would bond. The atoms of the top sheet would share electrons with the atoms of the bottom sheet. They would effectively become a single, solid piece of metal. You could not pull them apart without tearing the material itself.

This phenomenon is called “Cold Welding,” and it is the nightmare scenario for every aerospace engineer designing satellites, rovers, or space station components.

In space, a stuck hinge isn’t an annoyance; it’s a mission failure. If a solar array cannot unfurl because the pivot joint fused, the satellite dies. If a communication antenna cannot rotate, the probe is lost. The battle against this atomic fusion is one of the most critical, yet least understood, challenges of orbital mechanics.

The Oxide Shield

To understand cold welding, you have to understand why it doesn’t happen on Earth.

Our atmosphere is rich in oxygen. The moment a piece of metal is manufactured, it reacts with the air to form a microscopic layer of oxidation on its surface. This oxide layer acts as a barrier. It is dirty, chemically speaking. It prevents the pure metal atoms underneath from interacting with anything else.

In the vacuum of space, there is no oxygen. If a metal part rubs against another metal part and scrapes off that initial oxide layer, the layer does not regenerate. The raw, naked metal is exposed. When it touches another piece of raw metal, the atoms “don’t know” they are in different parts. They simply bond, creating a monolithic structure instantly.

The Failure of Liquids

The obvious solution would be to lubricate the joint. On Earth, we would just spray some WD-40 or pack the bearing with grease.

But liquids are volatile in a vacuum. In low pressure, liquids boil off at low temperatures. If you put standard oil on a satellite hinge, it will “outgas.” It evaporates into a cloud of molecules.

This creates two problems:

- The Joint Dries Out: The lubrication vanishes, leaving the metal bare and vulnerable to cold welding.

- The Cloud Condenses: The evaporated oil floats around the satellite and eventually sticks to the coldest surface it can find. Usually, that surface is the lens of a camera, a star tracker, or a sensitive sensor. The oil effectively blinds the satellite.

The Solid Solution: Molybdenum Disulfide

So, how do you lubricate a machine that cannot use oil and cannot rely on air? You use rocks.

Well, specifically, processed minerals. The aerospace industry relies heavily on “Solid Film Lubricants.” The most famous of these is Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2), often referred to simply as “Moly.”

MoS2 is a crystal that looks and feels like graphite. It is slippery. But its magic lies in its structure. It is “lamellar,” meaning it is made up of flat plates that slide over each other easily.

When applied as a bonded coating to a metal part, MoS2 creates a permanent, dry skin. It doesn’t evaporate in a vacuum. It doesn’t freeze at -400°F.

Crucially, it acts as a sacrificial barrier. When two coated parts rub together in space, the Moly sacrifices itself. The microscopic plates shear and slide, ensuring that the metal substrates never actually touch. As long as the coating remains intact, cold welding is physically impossible because the metal atoms are kept separated by the lubricant lattice.

The “Galling” Threat During Launch

The threat isn’t limited to orbit. It also happens during assembly and launch.

Aerospace vehicles are held together by thousands of fasteners—usually stainless steel bolts screwed into aluminum or titanium bodies. Stainless steel is notorious for “galling,” a friction-based form of cold welding that happens when you tighten a bolt too fast. The friction heat causes the threads to seize.

If a bolt galls during the assembly of a rocket engine, you can’t just unscrew it. It is welded shut. You have to drill it out, potentially ruining a million-dollar part.

By applying PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) or Moly-based coatings to the threads of these fasteners, engineers ensure that the torque tension is applied smoothly. The coating reduces the friction coefficient, allowing the bolt to be tightened to the exact specification without generating the heat that triggers a seize.

Conclusion

The success of the James Webb Space Telescope or the latest Mars Rover depends on thousands of moving parts performing a choreographed dance in the harshest environment known to physics. There is no mechanic to call if a wheel gets stuck.

The only insurance policy these machines have is the microscopic layer of material between their joints. These specialized aerospace coatings are not merely paint; they are the fundamental shield that allows humanity to explore the cosmos. They are the reason our machines don’t freeze into statues the moment they leave our atmosphere, ensuring that when we command a solar panel to open, it listens.