Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have found a galaxy that looks a lot like our Milky Way from the early universe, according to new research led by Marc Kassis of the Keck Observatory and published Friday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The galaxy, known as Alaknanda, is remarkably well-ordered a mere 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, overturning long-held assumptions about how rapidly galaxies can take on orderly disks with sweeping spiral arms.

Why It’s Surprising That There Is a Mature Spiral So Early

For decades, the accepted wisdom — supported by surveys from Hubble’s time — was that early galaxies were disheveled and chaotic, full of clumpy star-forming regions rather than the organized, rotating disks we see in modern-day spirals. Based on this theoretical picture, spiral features were only predicted to be rare for look-back times beyond about 11 billion years because young systems were assumed to be too dynamically “hot” to assemble into coherent structures.

Alaknanda challenges that narrative. That’s a clean, two-armed pinwheel (image below) with an estimated mass on the order of 10 billion suns, and it implies disks should settle down to form arms much faster than standard models predict. Researchers say such quick formation would mean more efficient gas accretion and angular momentum organization in the early universe than was believed to be the case.

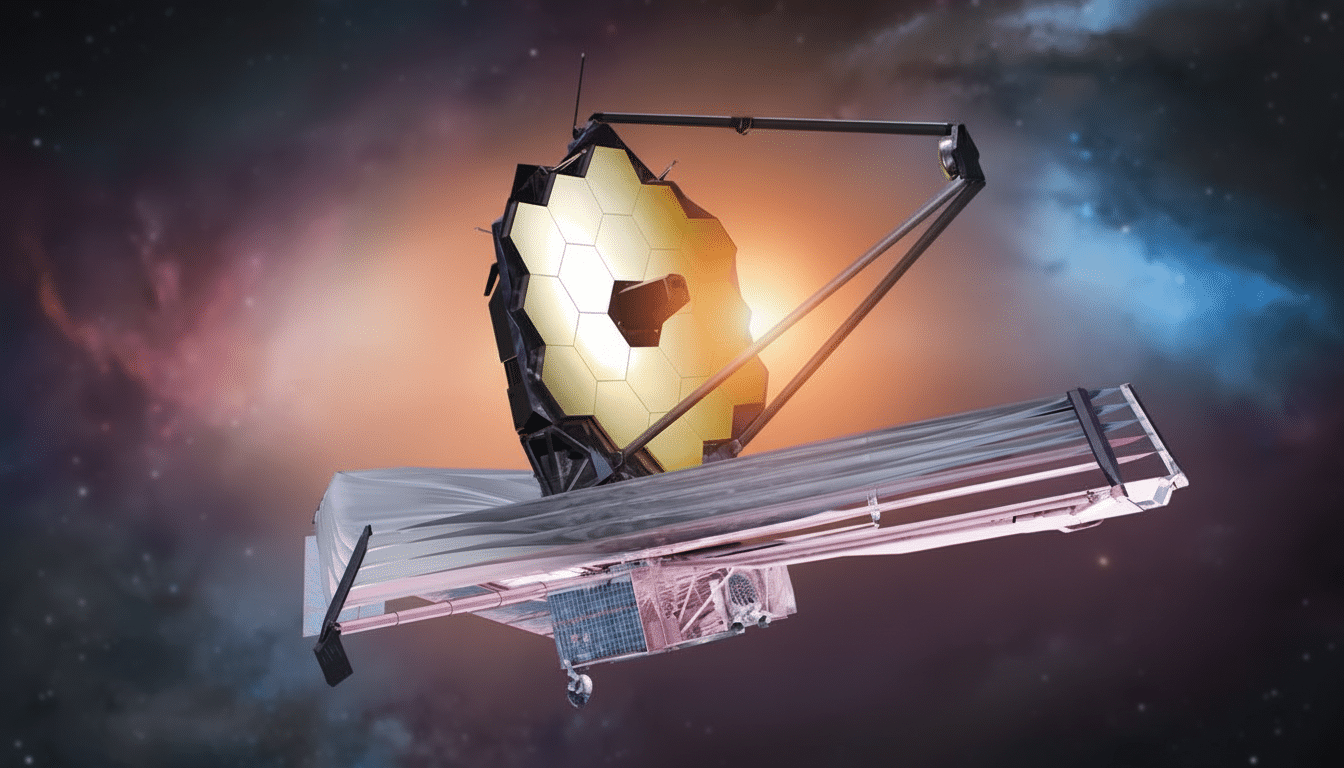

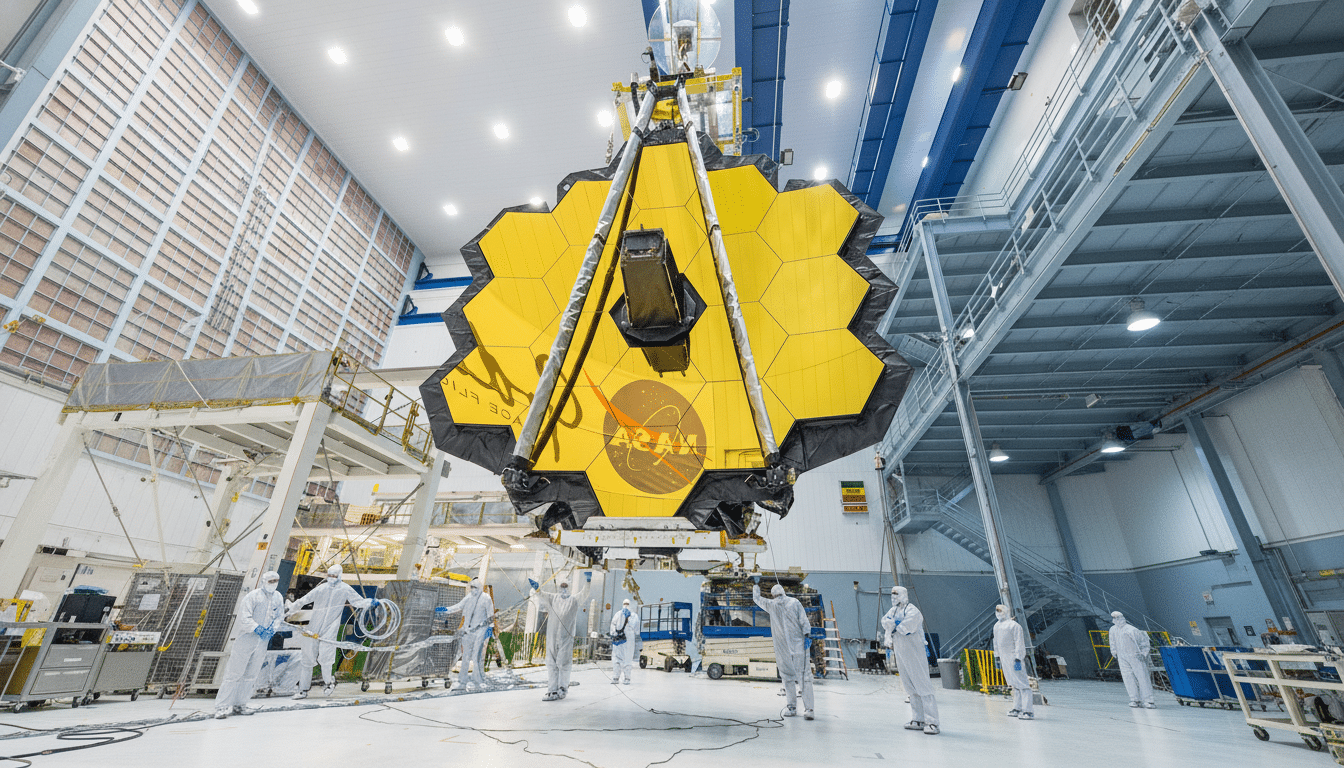

What Webb Saw and How the Telescope Captured It

Webb’s infrared vision revealed a flat, rotating disk some 32,000 light-years across — about a third the diameter of the Milky Way — sporting symmetric, well-defined spiral arms.

Dr. Wong and his team saw, running along those arms, chains of bright star-forming clumps like beads on a string — areas where gas has collapsed into eruptions of bright stars amid the dark rubble.

The observations got a little help from the universe: gravitational lensing by a massive foreground galaxy cluster acted like a magnifying glass enlarging Alaknanda, making it appear about twice as bright. That natural magnification, combined with Webb’s resolution, meant structural detail could be seen that would otherwise be beyond our ability to resolve at this distance.

Researchers used the galaxy’s light in 21 bands, from ultraviolet to infrared, and fit it to stellar population models. They found that the typical stellar ages were about 200 million years — showing that a late wave of star formation gave rise to most of the system after the universe had turned 1 billion years old.

A Galaxy That Grows Superstars at Breakneck Speed

Alaknanda is converting gas into stars at a rate of approximately 63 solar masses per year. That’s dozens of times faster than the Milky Way’s current rate of growth, which is usually in the range of 1 to 3 solar masses per year. Intense emission from ionized gas — a signature of intense star formation — further supports the picture of an actively growing disk.

As much as it is smaller than today’s spirals, Alaknanda’s orderly arms and smooth disk indicate less internal turbulence than anticipated for such an early time. If the disk’s stability parameter is poised near this threshold for fragmentation, then “it could naturally form long, coherent arms while still actively fueling rapid star birth,” she wrote — though it remains a tricky balance to strike in existing simulations.

Rethinking Galaxy Formation Models in Light of Webb

The find — reported by scientists at the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in India, and detailed in Astronomy & Astrophysics — adds to a short but growing list of early spirals discovered by Webb, such as CEERS-2112 and REBELS-25. Taken in concert, these systems suggest that rotationally supported disks and even grand-design structures formed earlier and more frequently than implied by previous surveys.

What it means for certain, say team members, is that a successful model must be capable of quickly settling the disks down and efficiently transferring their angular momentum toward the center and even into the formation of spiral density waves. Gentle nudges from companions in some cases: Alaknanda is interestingly located next to what could be its close neighbor that would give a small jolt to form its arms, but more data are required for confirmation of interaction.

What Alaknanda Is Up to Next in Follow-up Studies

Follow-up spectroscopy carried out with Webb’s integral field instruments can track how stars and gas move around the face of the disk, for example to check whether Alaknanda is in a steady, long-lived state or instead experiencing a brief spiral phase. Complementary radio observations will investigate its cold gas reservoirs, or the raw material of future star formation, and reveal how fast the galaxy is still able to form stars in the near future.

Exactly this sort of discovery is what the James Webb Space Telescope, a joint mission of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, was born to make: revealing unseen architecture from the early universe. For every high-redshift spiral it reveals, astronomers are compelled to move the timeline of galactic order back ever closer to the cosmic dawn — recalibrating that “maturity” and transformation is the norm.