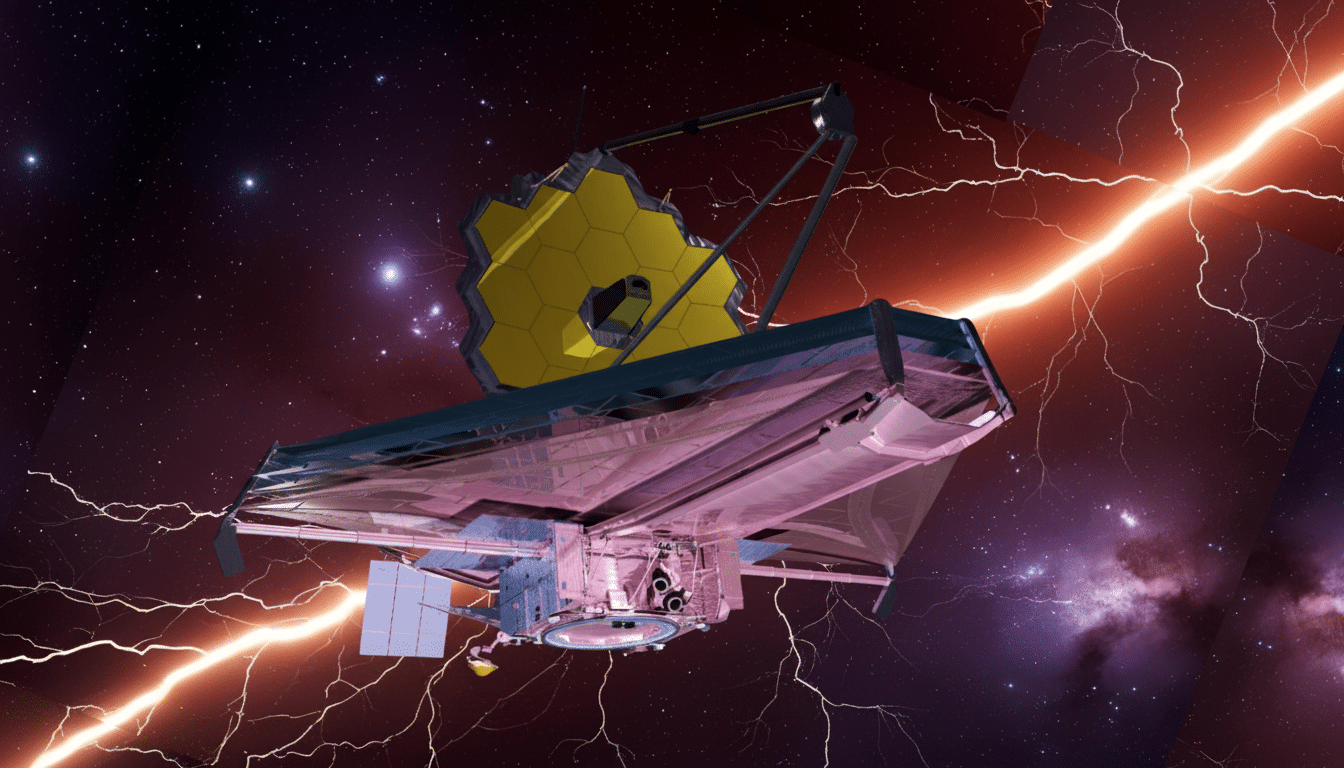

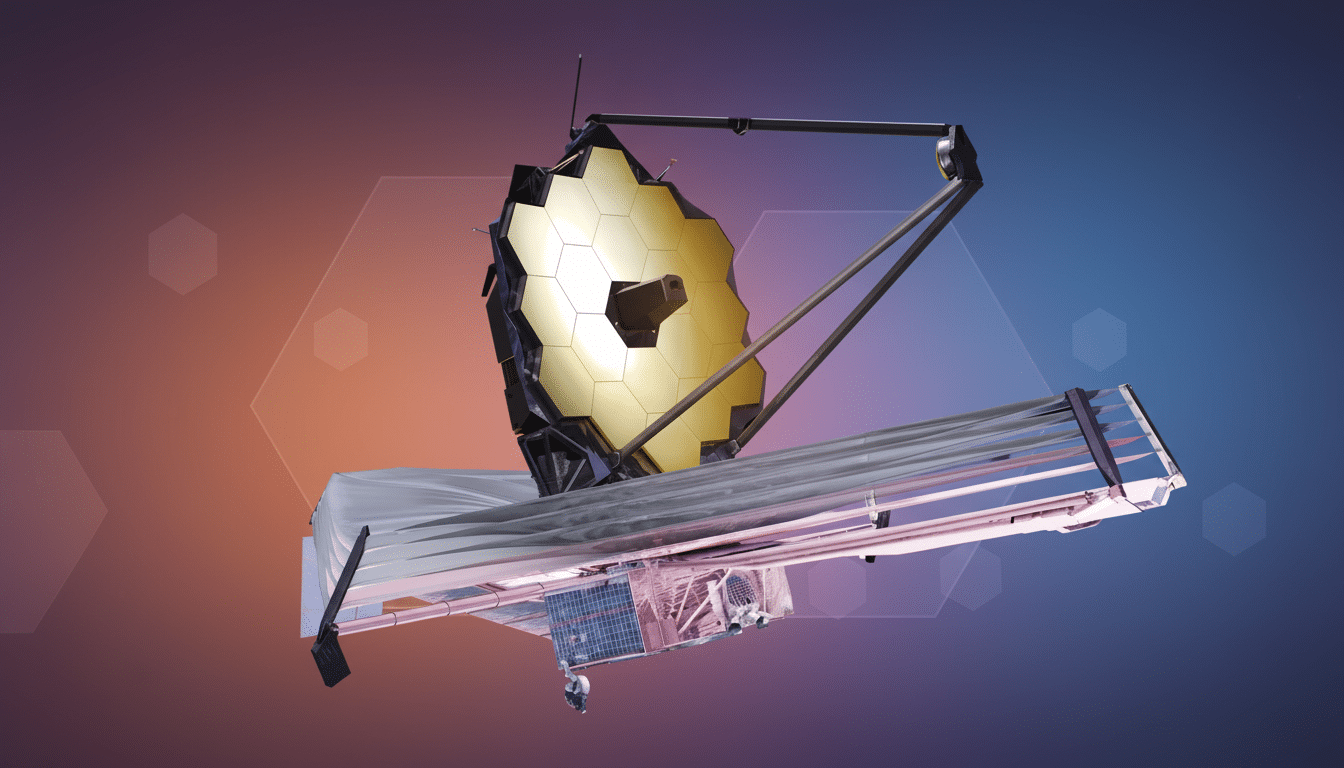

For the first time, astronomers have discovered a planet as Jupiter-y, doughnutty-looking as this one must look—squished like a lemon, or damp like an ocean rag (and, in fact, rather than breathing, it fills whatever air is around it)—and riddled with what would seem to be continuous egress and ingress of rosy gas. The planet, PSR J2322-2650 b, orbits a fast-spinning neutron star and seems to be cloaked in helium and carbon instead of the typical blend of hydrogen, water vapor, or methane. Made possible by the James Webb Space Telescope, the discovery, described in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, upends longstanding ideas about how planets form and endure in some of the most extreme places in space.

They explain that the carbon could form soot in the highest reaches of these atmospheres and potentially graphite or diamond deep within them, a process that has since stayed confined to science-fiction novels rather than already existing planetary models.

The find, with no clear origin story, has experts reconsidering the chemistry and evolution of planets blasted by extreme radiation and gravity.

How extreme gravity shapes a planet into a lemon-like form

PSR J2322-2650 b is a planet circling a millisecond pulsar located approximately 750 light-years from Earth. The crushed stellar core is spinning and beaming energy out as if it were a cosmic lighthouse, with gravity strong enough to stretch the planet next door into being prolate like a lemon. The distortion is characteristic of massive tidal forces felt on a microscopic scale.

The planet’s orbit is very close to the pulsar, about 1 million miles, many orders of magnitude closer than Earth’s orbit around the Sun. It orbits so quickly, taking less than eight hours to complete a circuit around the star, that a “year” on the planet passes between breakfast and dinner. That very close proximity creates a fierce temperature difference, from around 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit on the cooler hemisphere to perhaps 3,700 degrees on the side of the planet exposed to the star.

A carbon and helium atmosphere that defies prevailing models

Webb’s infrared observations indicate that the atmosphere of PSR J2322-2650 b is dominated by helium and simple carbon species, but with no evident signs of water, methane, or nitrogen chemistry, which may be indicative of mostly hydrogen-dissociated, disordered mantle envelopes typical of hot giant planets. Skalak and his team believe that for this carbon to last at such temperatures, there cannot be enough oxygen and nitrogen present, reversing the usual atmospheric recipe that scientists expect is common on gas giants.

Clouds on this type of world are likely to be more like soot than water. In a carbon-rich environment, molecules can polymerize into aerosols that darken the sky and absorb heat, changing the planet’s spectrum and energy balance. Under high enough interior pressures, carbon might crystallize into diamond, harking back to long-held ideas about what planetlike blobs of carbon would be like — but with a uniquely rare observational toehold.

What is striking about this case is the context. “A helium-and-carbon-atmosphere, Jupiter-mass object in a pulsar system is not the right kind of cookie for standard formation dough,” says co-author Shadab Albayati at CITA and Stanford University. “For example, it is hard in the current generation of models to imagine how you build up so many elements from very little without relying on severely stripping the gas or exotic chemical histories.”

Pulsar companions and the black widow scenario explained

Pulsars are infamous for blasting nearby companions with high-energy radiation and particle winds. Astronomers have dubbed some of these couples black widow systems, in which the pulsar slowly strips away an orbiting companion. PSR J2322-2650 b seems to be a planet rather than a star, but this planetary host is an odd species in this eroding act.

One idea is that the planet was once a gas giant, which had its lighter elements boiled off by the pulsar, to reveal a helium-rich envelope and carbon-heavy chemistry behind. Another possibility is that the companion is all that’s left of the core of a progenitor body. But none of the proposed paths completely accounts for the observed spectrum, which is more than anything else what makes the atmosphere unprecedented, according to the scientists.

Why this finding could change planetary atmosphere models

Among the more than 5,500 confirmed exoplanets listed by NASA’s Exoplanet Archive, a couple have suggested carbon-rich compositions amid past debates about planets like 55 Cancri e and WASP-12b. Yet despite decades of searching, good evidence for a helium-and-carbon atmosphere has been scarce. PSR J2322-2650 b extends the existing range for planetary chemistries and environments beyond the average.

The discovery has implications for how astronomers understand spectra in extreme systems. It challenges models to handle high C/O ratios, soot formation, and non-water chemistry cloud physics under irradiation. It also opens up the search space for exotic worlds, hinting that planetary atmospheres may be able to endure and even calm down under conditions that were previously dismissed as too violent.

What scientists plan to investigate with follow-up studies

Follow-up observations could chart how heat circulates along the stretched surface of the planet, keeping a log on phase-curve measurements looking at day-night contrasts. More spectra at different wavelengths would also check for carbon-bearing species, limit the helium abundance flux, and seek trace gases that could further refine the chemistry.

On the dynamics side of things, better pulsar timing will allow ever stronger limits to be placed on the mass and orbit of the planet, while more sophisticated interior models will investigate whether or not diamond layers are physically possible under the measured temperatures and pressures.

This may make the cross-checking process between Webb teams and ground-based facilities like Keck or the Very Large Telescope critical.

For the time being, PSR J2322-2650 b is a rare glimpse of nature in the laboratory. It squishes together issues of planet formation, atmospheric chemistry, and tidal physics into one lemon-shaped case study. If substantiated by more measurements, the carbon-laced skies may represent the most definitive example yet of a new class of worlds born and molded in the glare of a dead star.