The James Webb Space Telescope has stitched together an unprecedented time-lapse of Uranus’ auroras, following the ice giant for nearly a full rotation and revealing how its skewed magnetic field sculpts shimmering arcs at the poles. The sequence, built from sensitive infrared views of the planet’s upper atmosphere, doubles as the most detailed global map yet of Uranus’ ionosphere and shows it is cooler, thinner, and more uneven than expected.

Researchers using NASA’s joint observatory with ESA and CSA tracked the faint infrared glow of a charged molecule called H3+, a natural beacon for temperature and particle density high above the clouds. Because Uranus rotates in roughly 17 hours, the team could watch auroral patterns develop and drift across almost an entire Uranian day. The results, published in Geophysical Research Letters, offer the first three-dimensional look at how energy moves through the planet’s upper atmosphere.

A Lopsided Magnetosphere in Constant Motion

Uranus is a champion of extremes. It spins on its side with an axial tilt of about 98°, giving each hemisphere about 21 years of unbroken daylight followed by a two-decade night during its 84-year trek around the Sun. Its magnetic field is even stranger: the magnetic axis is tilted by roughly 59° relative to the planet’s spin and is offset from the planet’s center by a significant fraction of a radius. That off-kilter geometry makes auroras sweep and flare in complex paths rather than forming neat ovals like those on Earth.

Voyager 2 first revealed Uranus’ skewed magnetism during its 1986 flyby, and Hubble later caught tantalizing ultraviolet glows near the poles. But those snapshots lacked the continuous, planet-wide coverage that Webb’s time-lapse now delivers. By watching the auroras evolve over a full spin, scientists can see how magnetic field lines rotate, reconnect, and funnel energy into the atmosphere.

How Webb Built the Time-Lapse of Uranus Auroras

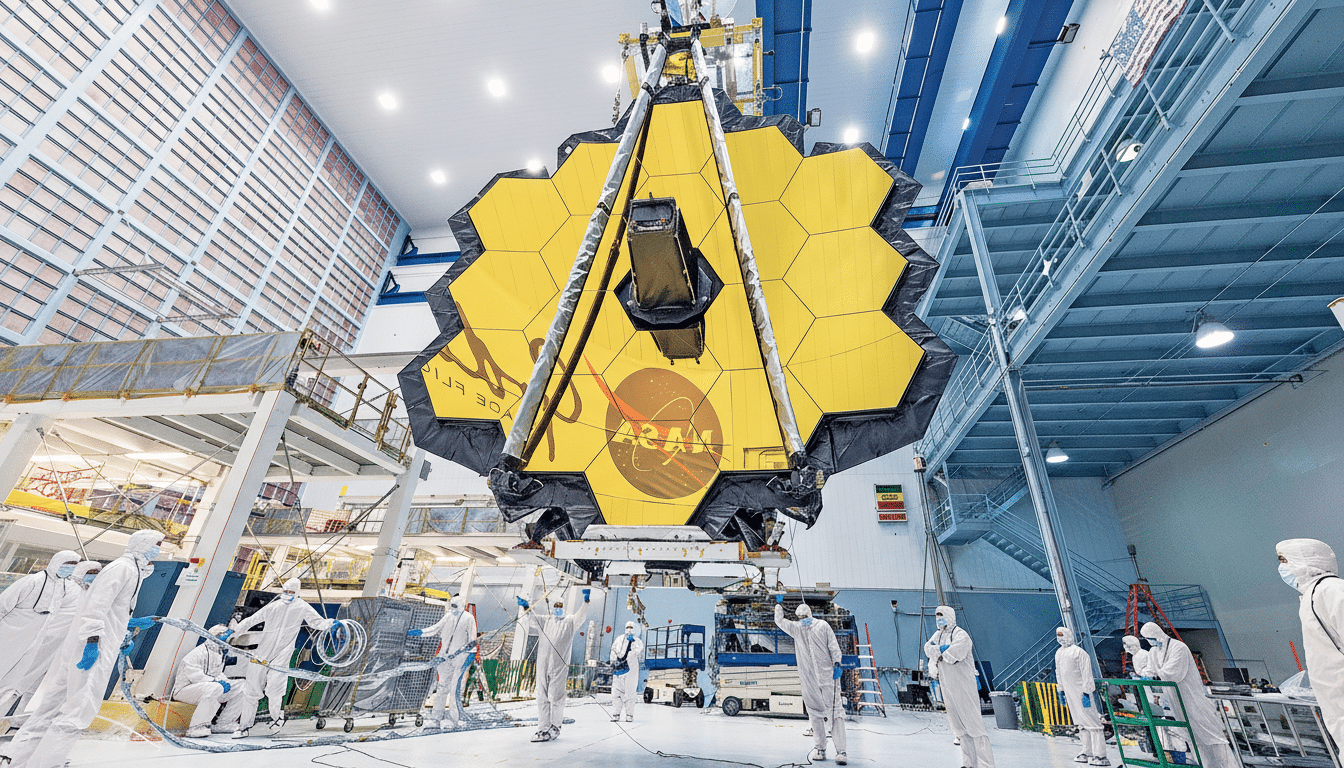

Webb’s near-infrared sensitivity makes H3+ emissions stand out, even at the frigid distances of the outer solar system—roughly 2 billion miles from Earth at certain alignments. The molecule forms when sunlight and charged particles ionize hydrogen and it radiates in well-known infrared bands, effectively acting as a thermometer and barometer for the ionosphere. By capturing a sequence of exposures and aligning them to Uranus’ rotation, researchers produced a clean, global time-lapse that also encodes temperature and density information with altitude.

The campaign, led by Paola Tiranti of Northumbria University with collaborators from institutions including the University of Leicester, leverages techniques honed over decades of ground-based monitoring from facilities such as NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility and the Keck Observatory. Webb pushes that work further by resolving faint, fast-changing structures that were previously smeared out or lost in noise.

What the Data Show About Uranus’ Auroral Physics

The time-lapse reveals bright auroral bands clustered near both poles, interleaved with dimmer arcs that wax and wane as Uranus turns. The intensity shifts suggest the planet’s offset field channels energy unevenly into different longitudes, likely modulated by pulses in the solar wind and by the twisted magnetotail snapping back toward the planet. Two persistent bright regions near the poles echo patterns seen at Jupiter, but their drift relative to the spin axis underscores just how tilted Uranus’ magnetic engine is.

Crucially, H3+ brightness points to a cooler, thinner ionosphere than many models predicted. That result extends a decades-long trend of declining thermospheric temperatures inferred from ground observations, indicating that Uranus’ upper atmosphere may be losing energy faster than it is being replenished. The findings will force a rethink of how waves, particle precipitation, and chemistry distribute heat through the planet’s rarefied upper layers.

Why It Matters Beyond Uranus for Exoplanet Science

Uranus is an invaluable stand-in for a vast class of exoplanets. Many worlds orbiting other stars are ice-giant analogs, and several show hints of misaligned magnetic fields. Understanding how a tilted, offset magnetosphere sculpts auroras and controls atmospheric escape on Uranus helps astronomers interpret exoplanet signals, from infrared emission to potential radio bursts. The new map of energy flows also offers a ground truth for space weather models used to estimate how harsh stellar winds strip atmospheres over time.

What Comes Next for Uranus Auroras and Webb Studies

With Uranus approaching a seasonal milestone that accentuates polar illumination, coordinated campaigns are planned across Webb, Hubble, and leading ground observatories to track how the auroras respond day by day. The results will feed directly into mission studies for a dedicated Uranus Orbiter and Probe, a top-priority recommendation from the latest National Academies decadal survey, by pinpointing where and when a spacecraft should sample the planet’s magnetic environment and upper atmosphere.

For now, Webb’s time-lapse offers a rare cinematic look at a distant giant’s space weather—an atmospheric light show choreographed by one of the most peculiar magnetic fields in the solar system, captured in detail that finally does its weirdness justice.