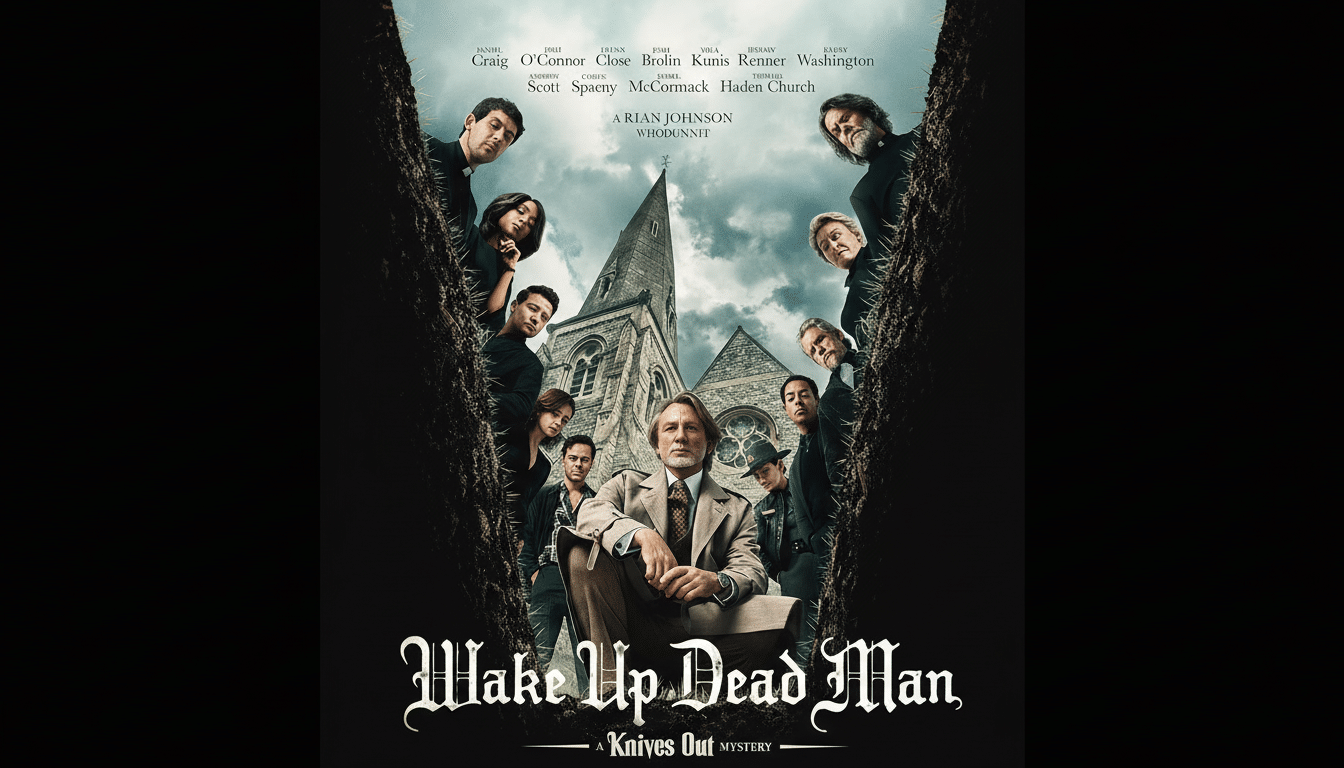

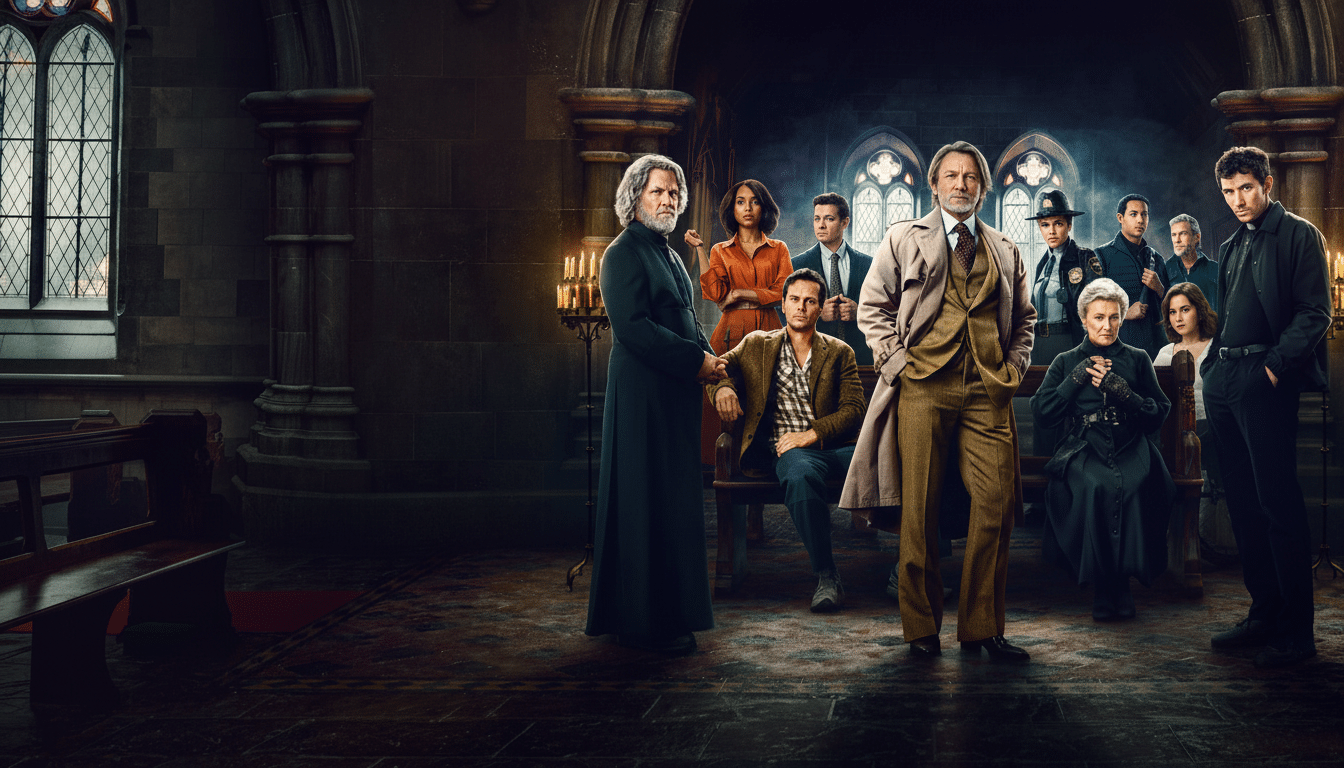

The smartest clue in “Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery” is right there on the cover if you know where to look. A handout from a church book club rears its head in the course of Benoit Blanc’s investigation, and its reading list, such as it is — sure to be dissected in some detail online once the movie has landed — functions effectively like a roadmap into and out of this thing. Parish busywork is really a crash course in locked-room lore and fair-play investigation.

The selections aren’t random. They trace the lineage of the impossible-crime story from ground-zero texts to village whodunits, heralding which subgenre rules are in play and which crooks hope you’ll let slide past.

The List Goes On Its Way to Locked-Room Lore

Front and center is John Dickson Carr’s The Hollow Man, the high altar of locked-room fiction. Its celebrated “lecture” by Dr. Gideon Fell (a looping, taller version of Keats) sets forth how to do murders that seem physically impossible, a precept so persuasive that mystery scholars today still use it as a kind of taxonomy of tricks. Published in the United States as “The Three Coffins,” this book is a perennial touchstone for impossible-crime writers, and also a wink to viewers that mechanics matter as much as motive.

The nod is all the cheekier given the setting. This mania for fair play was embraced and outlined by Father Ronald Knox in his “Decalogue” of commandments for the detective story, created by a priest who was also a critic and that became the creed of the Detection Club. A church club promoting Carr feels like a serving sermon on the morals of clueing.

Christie Pews Cornerstones of Parish Crime Mysteries

Two Agatha Christies make the sheet: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and The Murder at the Vicarage. The former is a perennial poll-topper (it was, at one time, voted the greatest crime novel by the Crime Writers’ Association) famous for its audacious but scrupulously clued solution involving Hercule Poirot. That’s Christie showing how misdirection can be fair and also devastating.

The second throws Miss Marple into a parish mystery that transforms gossip, routine and small-town sanctimony into weapons. A murder in a clergyman’s study, a village where people know everything about everyone, and a sleuth who trusts patterns of human behavior over bravura stunts — it is the perfect thematic mirror for a church-set case that treats community as both comfort and cover.

Fathers of Detection on the Sheet Shape the Genre

So too is Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue, and with it the kick-starter for detective fiction itself. Poe’s amateur sleuth C. Auguste Dupin not only invents the business of puzzling out clues, as if they were Braille on a wall raised against meaning; he also invents narrative mechanisms (like Paul Temple’s wife or Sherlock Holmes’ clueless reflection, Watson), and even the ordinary device of there being such an impossible situation to tackle — the locked room itself set up to be the antecedent humbug that will put the gag in place against investigators. His effect on Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes is recognized by scholars of such pastiche from the Library of Congress to the Mystery Writers of America.

Sayers Sets a Lasting Tone of Classic Fair Play

Dorothy L. Sayers’ Whose Body? presents Lord Peter Wimsey with a mystery as memorable as its photograph: a naked corpse in a bathtub that is shod only in pince-nez. The novel exemplifies the “fair play” pact — clues are there if you know how to look for them — and Sayers, a founding member of London’s Detection Club, helped shape the clue-puzzle tradition that Wake Up Dead Man gleefully raids.

Why It Is Worth the Film’s Time to Teach Its Rules

Rian Johnson doesn’t just homage the Golden Age; he weaponizes it. By planting a reading list that doubles as a syllabus, the film telegraphs its rules: anticipate mechanical ingenuity, face-value clues and character psychology in guise of parish politeness. For reference, Agatha Christie is the world’s best-selling novelist by a wide margin with an estimated 2 billion copies in print (via her posthumous publishers Agatha Christie Limited) — a reminder that these narrative templates are part of the commercial DNA.

The British Library’s Crime Classics series has added to its reissues of Golden Age mysteries over the years, reflecting a continuing appetite for puzzle-first entertainment. Wake Up Dead Man siphons from that same well, tasking viewers to read the crime like a book club would: one chapter, one clue, one hypothesis at a time.

The Onscreen Book Club List as a Mystery Syllabus

The titles seen on the Our Lady of Perpetual Fortitude handout are:

- The Hollow Man — John Dickson Carr

- Whose Body? — Dorothy L. Sayers

- The Murders in the Rue Morgue — Edgar Allan Poe

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd — Agatha Christie

- The Murder at the Vicarage — Agatha Christie

Think of it as the case file before the case file.

Read them and you’ll hear echoes throughout — including, perhaps immodestly, if no other voice were ringing in my ear: Benoit Blanc’s own reasoning a half-beat before he says it out loud.