Strange objects: These could be the building blocks of galaxies — or something else entirely.

Astronomers combing through data from the fledgling James Webb Space Telescope have found a mysterious population of miniaturized, super-red sources from the young universe that they believe to be neither ordinary stars nor normal galaxies. Instead, the evidence seems to favor an unusual candidate: “black hole stars” — supermassive black holes shrouded within bright sheaths of gas that dramatically change the way they appear and mask their usual telltale signs.

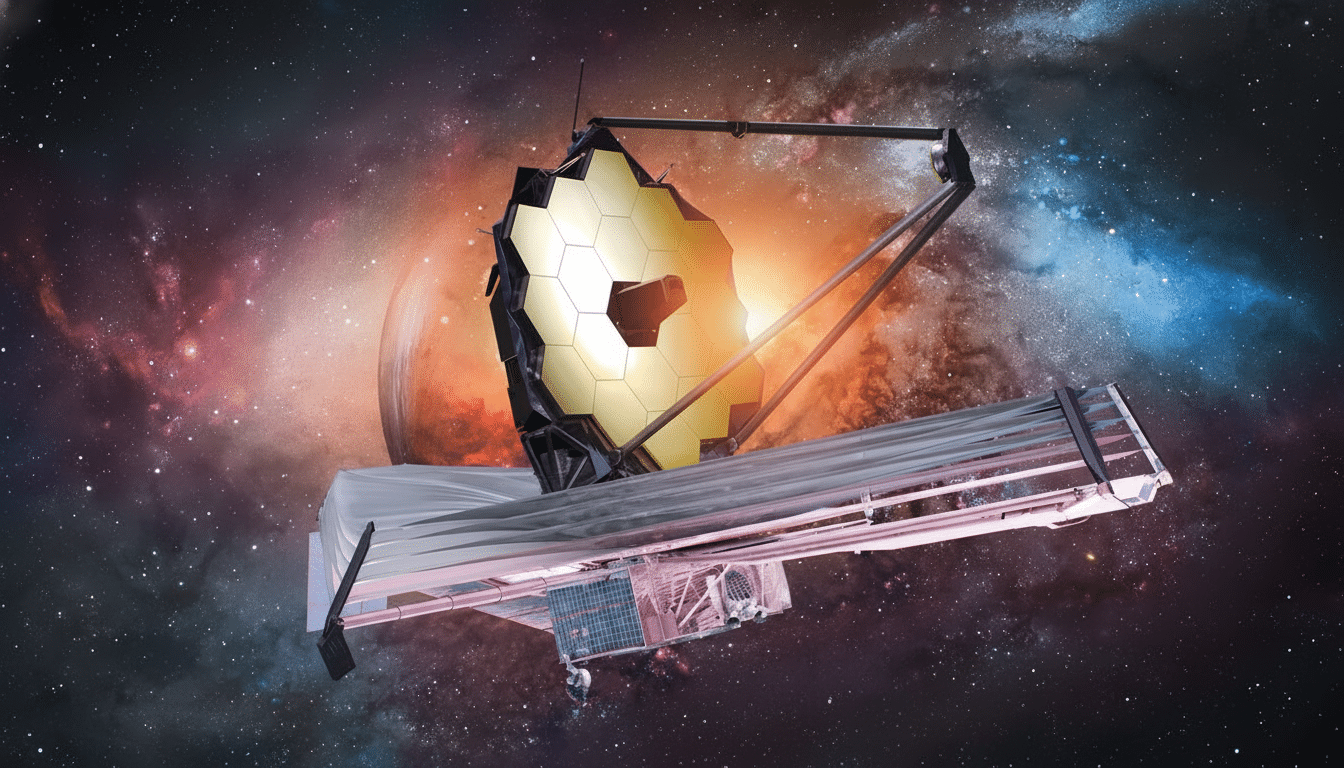

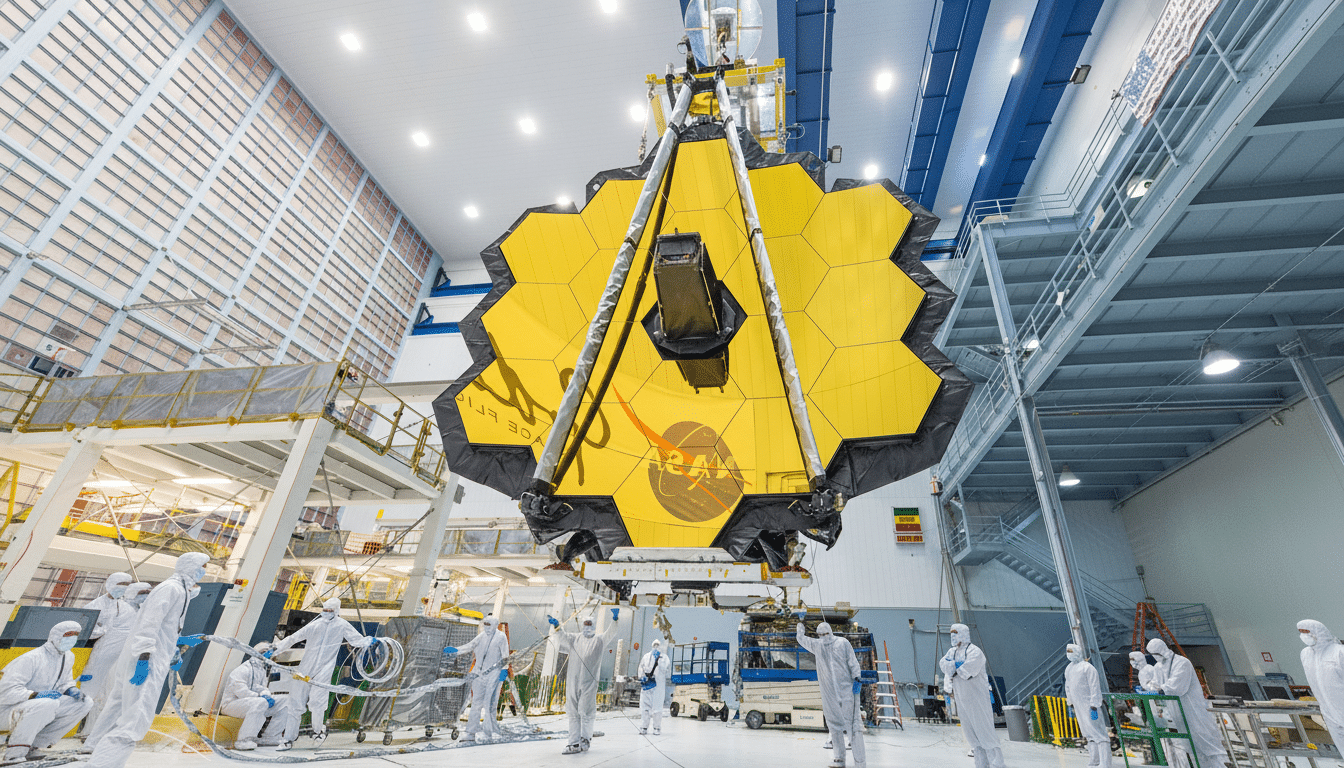

The concept arises from a yearlong Webb survey of 4,500 distant galaxies that identified one particularly extreme object, informally named “The Cliff.” These results, published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics by an international team using NASA, ESA, and CSA’s flagship observatory, strengthen a new explanation for the so‑called “little red dots” that has been debated since Webb first observed its deep images.

What Webb saw in the ‘little red dots’ of early cosmos

When such tiny red objects started cropping up in early Webb observations, some teams claimed the objects looked suspiciously like mature, humongous galaxies that had taken shape just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang; a scenario that is difficult to square with established models of galaxy formation.

Webb’s infrared view, which captures light stretched by cosmic expansion, showed extremely bright but tiny objects.

“The Cliff,” as it’s known, is more than twice as powerful as the most similar sources and only about 40 light‑years across — even smaller than a typical galaxy, more like a dense stellar cluster in size, yet far brighter.

Crucially, no X‑ray emissions — which are frequently the smoking gun of ravenous black holes — were seen from this source in the data we had.

That absence defies the easiest explanation of a naked accreting black hole shining in the open, by doing nothing more than being its own kind of classic quasar.

A buried engine: the ‘black hole star’ explained

The research suggests that a fast-growing black hole may be ensconced in a hot, dense envelope of hydrogen gas. As infall material emits energy, the gas is lit up and becomes so bright and optically thick that it overwhelms these features in the spectrum, to such an extent that in its totality it scatters or reprocesses light into something which looks rather less like a galaxy or quasar and more like a single supersized star.

This situation resembles the decades‑old theoretical concept of dormant “quasi‑stars,” which were suggested to be transitory newborn objects in the early universe, around which black holes grew within an immense starlike cocoon. In Webb’s new observations, the envelope would tend to dampen out X‑rays and instead create an extremely red, compact glow which is what we are seeing.

There’s a… uh, mysterious prominent feature of “The Cliff”’s spectrum and the local system is that it looks more star‑like in ways tracing back vital signs than ever seen before, but orders of magnitude too bright and concentrated for any known class to which we can compare (the talk slides literally say “eat your heart out, hot stars!” [I can quantify those words if someone makes me or I get my hands on FOCAS data]). It’s the mismatch that drives the black‑hole‑inside‑a‑star model.

A fast track to monster black holes in the early universe?

If confirmed, black hole stars may solve a long-standing mystery: how supermassive black holes managed to become millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun so soon after the dawn of cosmic time. Standard pathways — sluggish accretion from run-of-the-mill stellar remnants — have a hard time keeping pace with the deadlines implied by the earliest quasars.

An enveloped engine has many benefits for rapid growth. By smoothly feeding gas in and concealing hard radiation behind the blanket, the system might suppress blowing itself up. That would enable the seeding of the supermassive black holes that are now present in all, or nearly all, massive galaxies, including our own.

A weird mix of hot and cool gas in a tiny region

Not everything neatly fits. Spectra suggest incredibly hot, fast‑moving material existing alongside some surprisingly cool material, all in this tiny region. One of the main theoretical challenges that the team is still wrestling with is how to reconcile these conditions — and their dynamics.

Perhaps shocks and outflows from the hidden black hole are churning up the envelope, creating pockets that have extremely different temperatures and densities. The other is that it flickers, briefly revealing cooler layers and a smothered inner engine most of the time.

What will make the case for black hole star origins

The clinching tests will be provided by deeper spectroscopy. “We can use Webb’s NIRSpec and MIRI instruments to spectroscopically hunt for specific lines — helium‑II, and hydrogen recombination lines, for example — that reveal intense radiation fields pervaded by dense gas,” says McLure. The absence of strong, hard X‑rays would keep on favoring an envelope engine rather than a naked quasar.

At the same time, ALMA can search for cool gas and dust at millimeter wavelengths, and observatories such as Chandra and XMM-Newton can push the X-ray bounds. If more than one “little red dot” shares the spectral fingerprints of “The Cliff,” evidence for a new class will mount quickly.

Regardless, these little red mysteries illustrate that Webb is doing exactly what it was constructed for: finding surprising objects in the universe’s first performances. Whether they are black hole stars, quasi‑stars, or something weirder yet, they are compelling a rewrite of the history of how the earliest cosmic engines blazed to life and began burping up material.