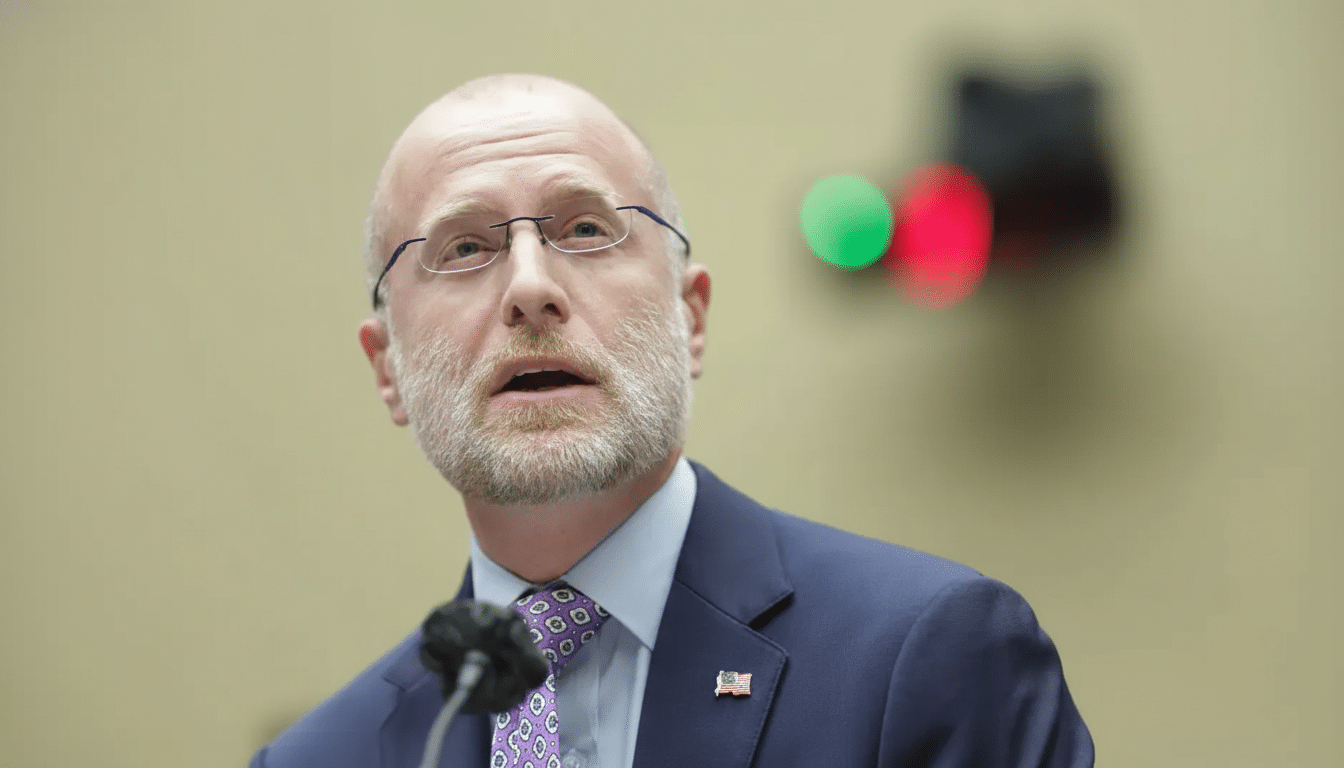

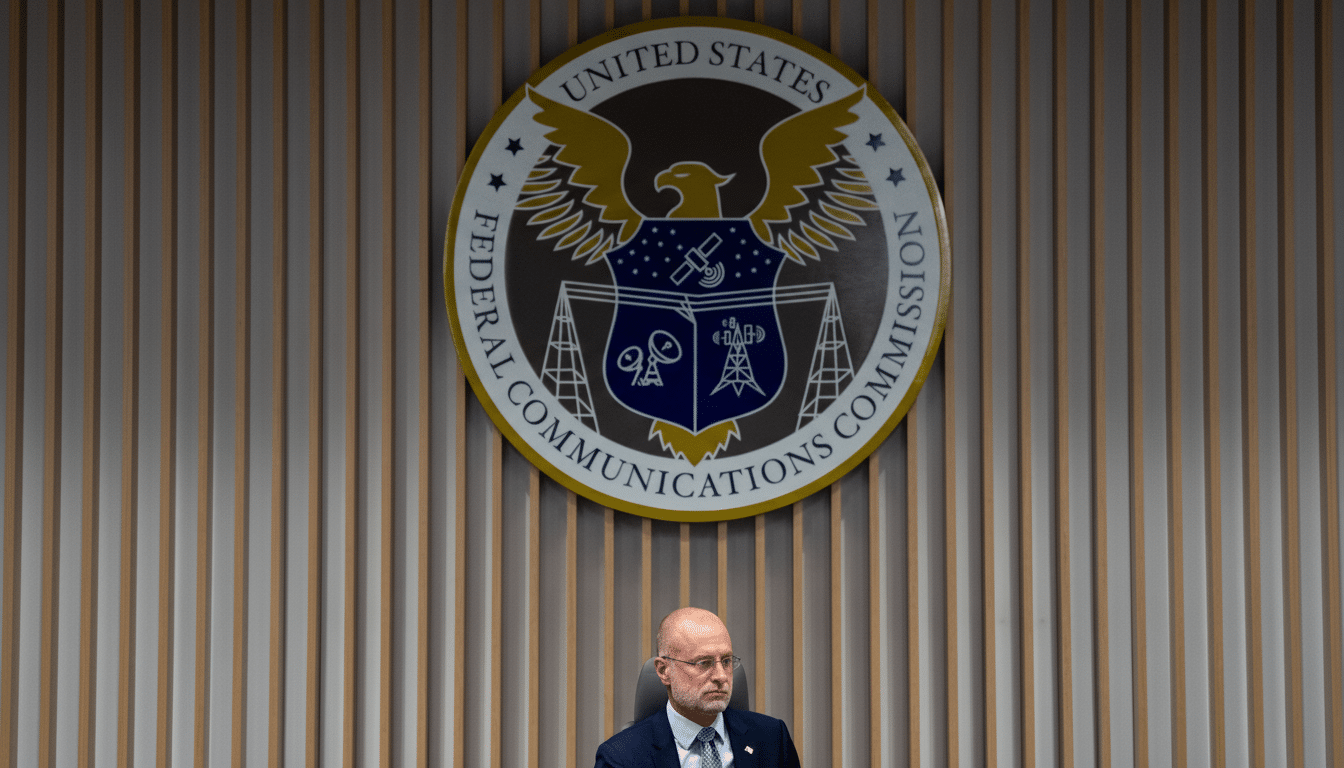

The Federal Communications Commission voted 2-1 along party lines to do away with minimum cybersecurity requirements for phone and internet providers, at a time when new evidence of China-backed incursions against U.S. telecom networks has begun to trickle out. Republican commissioners Brendan Carr, who served as chair until Wednesday, and Olivia Trusty supported the rollback of the regulation, while Democrat Anna Gomez dissented, warning that stripping away this oversight would remove “the agency’s only enforceable baseline to protect critical communications infrastructure.”

The outdated framework, which was adopted in the final months of the previous administration, required carriers to implement specific commercially reasonable actions to protect against illegal access and interception of communications. The vote passes much of the oversight to voluntary measures — putting carriers in the position of having to determine how far they want to go, and leaving regulators without as many tools if those efforts fall short.

What Changed and Why It Matters for Telecom Security

The overturned rules were designed to set a floor, not a ceiling: the industry should have basic protective controls in place; risk assessments were required but tied to well-recognized standards (it’s not just any manipulation that would trigger rejection); and there would be consequences for bad things happening if you didn’t protect network gear and lawful-intercept equipment. Skeptics say that without binding standards, the weakest links could remain in the ecosystem, disproportionately among smaller and regional providers that don’t have the scale or resources of national carriers.

Telecom networks are the foundation for emergency services, government communications, and enterprise connectivity. Compromise of backbone signaling systems, network edge routers, or lawful access platforms can facilitate surveillance, traffic manipulation, and denial of service. Stripping away baseline requirements does not stop carriers from investing in security per se, but it relaxes outside pressure to solve known systemic weaknesses that adversaries exploit over and over again.

A High-Risk Backdrop: Recent Intrusions and Exposure

The vote comes in the wake of revelations about a yearslong campaign by a China-backed group called Salt Typhoon to breach more than 200 telecommunications providers, including household names such as AT&T, Verizon, and Lumen, according to people familiar with incident briefings. The intrusions appear to have focused on wide-ranging surveillance, including investigating or accessing wiretap systems that would meet the definition of lawful intercept under U.S. law, prompting concerns about the viability of lawful electronic surveillance.

Federal cyber agencies have warned that state-sponsored actors are repeatedly exploiting old vulnerabilities, default credentials, and unmonitored equipment in carrier environments. Joint advisories from CISA and the NSA have also pointed to continued targeting of edge devices and remote management interfaces, and industry analyses from Microsoft and others have mapped sustained Chinese activity against network infrastructure. In this context, Commissioner Gomez further contended that voluntary guidance — however well-intentioned — had not been effective in closing the gaps that attackers really exploit.

Industry and Capitol Hill Response to FCC Rollback

Key lawmakers quickly pounced on the rollback. The chairs of the Senate Homeland Security and Intelligence committees cautioned that the FCC was tearing down basic protections without a credible alternative, which could leave consumers and government communications even more vulnerable. Their concerns mirror recent Government Accountability Office findings that critical infrastructure sectors require enforceable baselines to underpin consistent risk reduction.

Industry groups, spearheaded by NCTA, reacted with approval to the action, which they described as “overly prescriptive,” arguing that flexible, risk-based programs in line with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and existing FCC advisory best practices are better suited to manage. Big carriers say that significant internal investments, such as dedicated security operations centers, threat sharing, and vendor evaluations, are proof that mandates aren’t necessary.

Gomez pushed back, saying that cooperation alone hasn’t stopped government-backed intrusions. Without punishment for the risks of not patching core holes, failing to segment sensitive systems, or to harden lawful-intercept platforms, she added, the sector remains susceptible to the same playbooks that starred in recent campaigns.

What Happens Next for Carriers After the FCC Vote

With no federal floor, carriers will rely on voluntary frameworks — NIST CSF 2.0, CISA’s Secure by Design principles, and FCC advisory council guidance — and calibrate spending to their risk tolerance. The larger providers will likely keep current programs in place; the bigger question is whether smaller and rural operators will underwrite expensive upgrades such as:

- Continual asset discovery and inventorying

- Following least-privilege access protocols

- Using multifactor authentication on all administrative systems

- Paying for independent security testing and validation

Other telecom-focused rules remain intact. The FCC’s Secure and Trusted Communications Networks initiative is still reining in usage of higher-risk gear from Chinese vendors, while there are further obligations for carriers relating to customer proprietary network information. But such measures are aimed at supply chain violations and privacy breaches, not the day-in, day-out hardening of routers, optical transport, signaling, and intercept components targeted by more advanced actors.

The Stakes for Consumers and National Security

For consumers, the immediate effect might be invisible — until it isn’t. In the worst case, network compromises can spiral into outages, location tracking for espionage, interception of calls and texts, and fraud. For government and essential industries, the threats might be espionage, 911 service disruption, and subversion of trusted communications. In an industry in which adversaries are searching for the lowest-hanging fruit, the lack of uniform minimums means that a breach of a smaller carrier is more likely to be used as a pathway into larger networks.

Anticipate pressure to shift to Congress, state regulators, and the market. Lawmakers could impose narrowly crafted mandates around high-risk systems like lawful intercept, signaling, and edge device management. In the meantime, it’s on carriers to prove measurable security yields — fewer exposed management interfaces, faster patch cycles, and independent validation — beyond mere paper assurances. With the most sophisticated threats already embedded in parts of the nation’s core, the room for error is small.