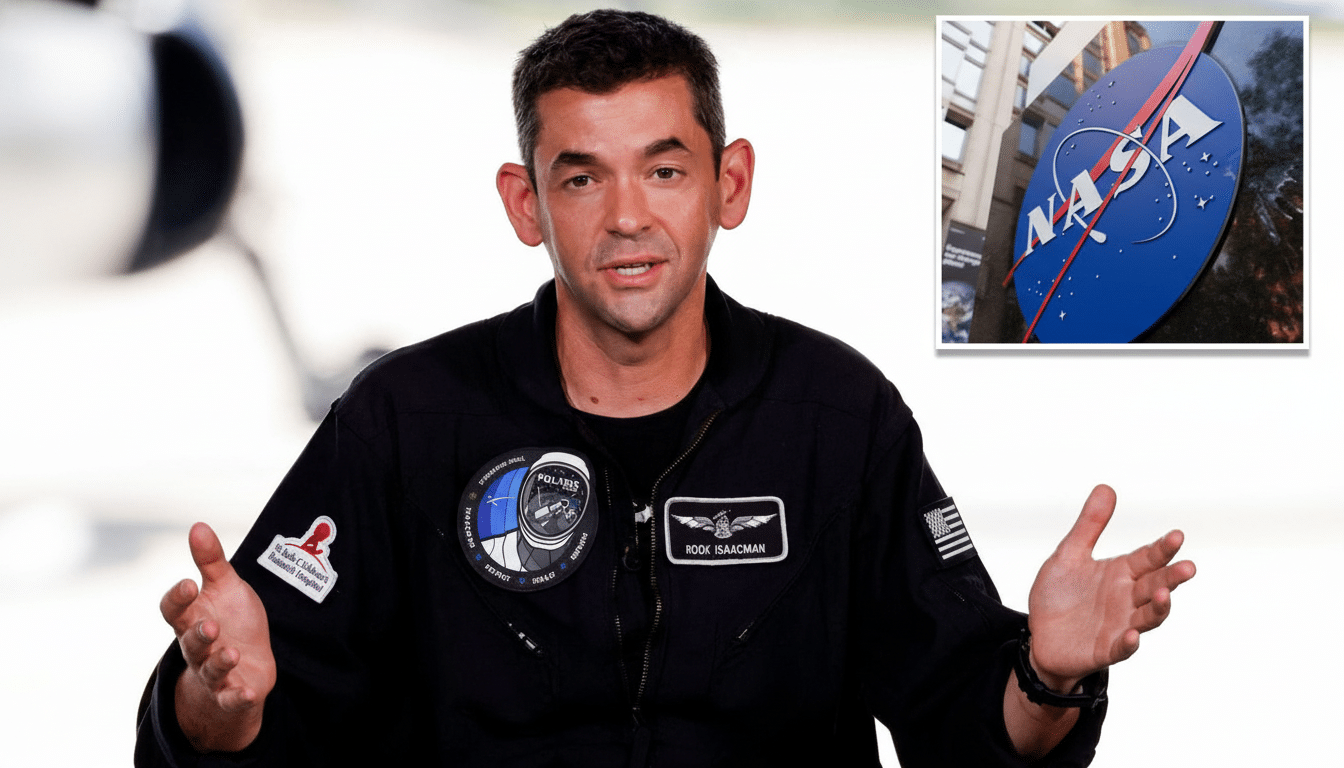

Former President Donald Trump is again turning to private astronaut and tech entrepreneur Jared Isaacman as his nominee for NASA administrator, reviving a high-profile pick that was yanked earlier. The move reignites the debate over just how aggressively NASA should pivot toward commercially led exploration — and what that means for Artemis, the International Space Station and the agency’s scientific portfolio.

What Changed This Time in Isaacman’s Renomination Bid

Isaacman’s initial nomination was abruptly yanked after allies said the candidate didn’t fully share the administration’s overall goals, according to reporting at outlets such as Ars Technica. The renomination signals a resumed calibration: This time, Trump is emphasizing Isaacman’s astronaut cavortings, his stature as an embodiment of the (Buzz Aldrin-driven) approach that New Space should operate with markets chasing pluckiness rather than stolid national aims and at risk due to events or outputs governed by mopes who slow-play cutting-edge implementations at NASA.

The revived push follows wider policy jockeying over the direction and budget of NASA. Draft proposals under discussion in the Capitol would call for deep cuts to some legacy programs and a greater reliance on commercial systems. A move like that would require a leader who is comfortable with public-private partnerships and rapid test-and-learn cycles — characteristic backers of Isaacman say he has in spades.

Who Jared Isaacman Is and His Path to NASA Leadership

Best known for founding the billion-dollar company Shift4, Isaacman paid out of his own pocket to lead Inspiration4 — the first-ever all-civilian mission into orbit — and also headed up the Polaris Dawn flight on board SpaceX’s Crew Dragon. Polaris Dawn reached an altitude of approximately 870 miles, higher than any crewed mission flown by the United States since Apollo, and tested on-orbit communication via SpaceX’s Starlink network.

Drawing from both of those pools, in decades past several NASA administrators have rocketed to the top job from Congress, military service or other roles at NASA; but none has brought with them Isaacman’s mix of private capital, experience flying a space shuttle, and large and direct commercial partnerships.

Advocates say that perspective could expedite timeframes. Skeptics respond that managing a giant federal agency with a civil service workforce of roughly 18,000 requires different skills — and careful attention to program administration and safety.

What His NASA Agenda Would Look Like Under His Leadership

Isaacman has shared concepts of a data-informed restructure that would eliminate layers of oversight, create more astronaut flight opportunities and focus on extending the useful life of the ISS while seeding a sustainable commercial foothold in LEO. A draft framework nicknamed “Athena,” described in industry chitchat as well as in congressional staff briefings, suggests the universe of programs will be sorted by how much they overlap or duplicate and by giving incentives to those that come in on cost and schedule.

Fixed-price, milestone-based contracts, similar to the Commercial Crew and Cargo models, will continue to be relied upon. Independent overviews from the Government Accountability Office and the NASA Office of Inspector General repeatedly have said such arrangements are not a panacea, but have served up competitive costs and faster iterations when combined with stringent insight and safety oversight.

Any quick retooling would also need to learn from recent test campaigns. SpaceX’s Starship, for instance, has shown potential with high-profile failures common to early-stage development of a heavy-lift vehicle. New Glenn by Blue Origin flies out of initial flight testing as well. The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel has recommended that NASA “balance the need for haste and the imperative to fly safely with systems engineering discipline” — advice that will be difficult to follow for a new administrator.

Politics and the Road to Senate Confirmation for Isaacman

The administrator position requires Senate confirmation, and Isaacman’s private-sector connections will come under scrutiny. Lawmakers are sure to question potential conflicts of interest, the plans for his recusal on matters involving SpaceX and other vendors, and how he would protect scientific integrity while promoting commercial partnerships.

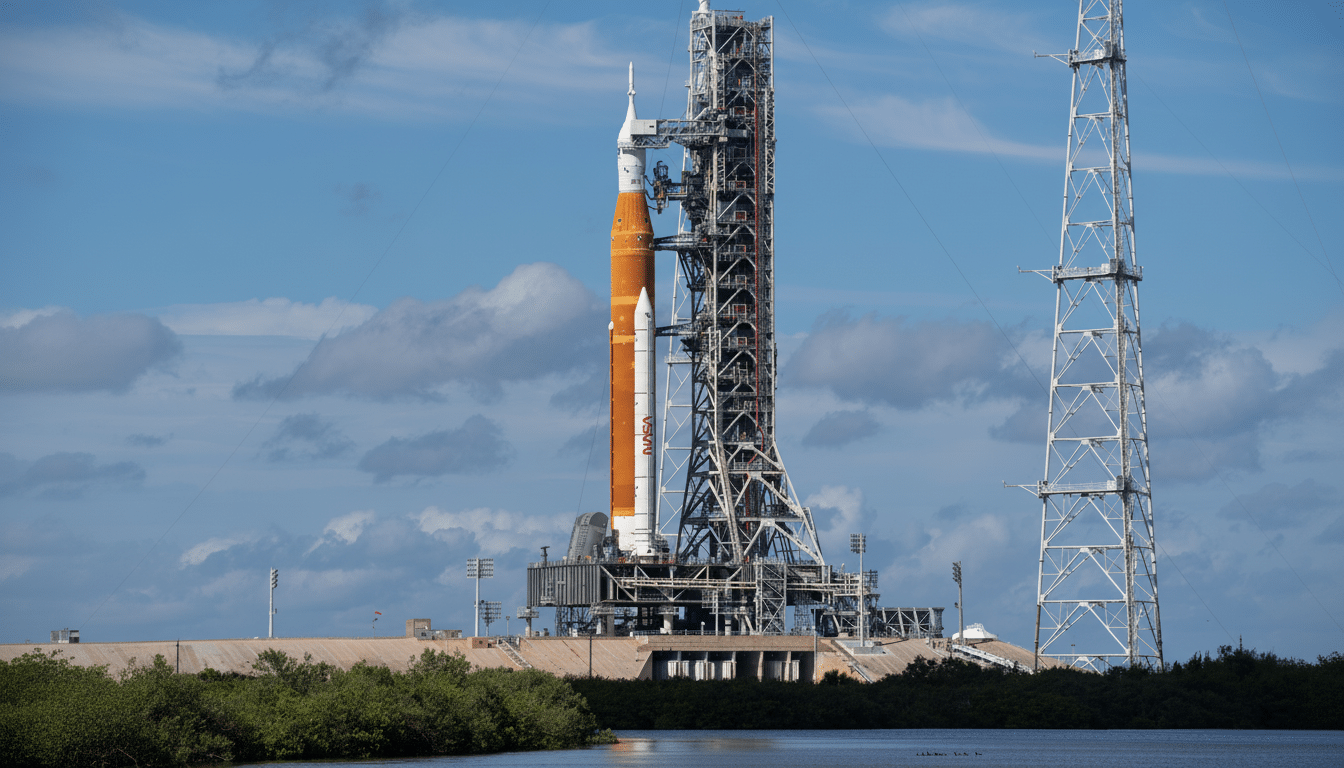

Then there’s the budget fight. Proposals that have been moving around Washington have sketched 24% or so in cuts to the agency’s top line, as well as a bit of program-shuffling: scaling down the Space Launch System while playing up its commercial heavy-lift competition. Those numbers, disputed and not yet final, would entail difficult choices across human exploration, Earth science and planetary missions. The Congressional Research Service has cautioned that such funding lurches frequently lead to schedule slips and more-expensive long-term costs.

The Stakes for Artemis and Low Earth Orbit

Artemis remains the bellwether. To land crews on the Moon, NASA needs to work with Orion, SLS or commercial heavy lift; lunar landing vehicles; suit systems and surface habitation while certifying the vehicle for human spaceflight. The GAO has identified integration risk as the leading cause of delay over and again. A commercially focused administrator might press to send more pieces to industry, where NASA could tighten its focus in systems architecture and safety assurance.

NASA aims to move from the ISS to commercial stations in low Earth orbit. Even NASA’s own studies show that a seamless handoff is needed if there is to be no research and workforce gap. If, on the other hand, Isaacman values regular crewed flights and targeted technological demonstrations — life support, on-orbit manufacturing or advanced communications technologies — he could spark a more lasting orbital economy that still would save many essential microgravity experiments.

The big question is whether the Senate, the White House and industry can find common ground around scope, schedule and funding. (If they sync, Isaacman’s second chance could herald a definitive pivot toward a quicker and more commercially integrated NASA.) If not, the most ambitious agenda will collide with the gravity of budgets, bureaucracy and physics.