Linus Torvalds has a terse message for those who submit code to the Linux kernel: Your new feature should not be surprising, interfering with other people’s work, or out of sync with the rest of the code. And he adds: You also should not “write a commit message that doesn’t actually explain what the patch does.”

In the last couple of days the creator of the kernel batted away a proposed change that had a reference pointing back to the same information that is already in the patch discussion. He’s not angry about etiquette; he’s angry about time. When a link does not lead to new information — a crash log, a discussion thread, an entry in a bug tracker — it traps maintainers into chasing dead ends, and this slows everyone down on the project.

Why “Link:” tags are in the crosshairs

Kernel patches typically provide a “Link:” trailer which identifies the issue source or where the broader discussion can be found. Torvalds’ gripe is that links that recur to the same email, a generic project page, a dumb explanation, even if it doesn’t encapsulate you, are “not because it means people now have to actually look at the damn thing instead of silently auto-including it as a dependency.” In the case he flagged, he anticipated a link to an error report or a discussion that explained the change. Instead, the link contained nothing he hadn’t already read, and the patch appeared superfluous, even worse, untrustworthy.

Linux’s own documentation on sending patches urges references that provide context in expansion—bug reports, mailing-list threads and test artifacts—not filler.

A “Link:” is to get provenance and rationale, not ticks on a template).

Automation and AI are a problem

Contemporary tooling makes it easy to add noise. Repository services automatically insert cross-references for issues, merge requests and emails. Programmers increasingly rely on AI assistants to write code commit messages. The result: You get a rush of automatically generated “Link:” lines that don’t enhance understanding. And as AI continues to be more widely used across software teams — here’s an insight I’ve seen repeated in several developer surveys like the Stack Overflow survey — so too the danger of low-signal and bland summaries passing themselves off as documentation.

Torvalds’ stance is not anti-automation. It is pro-signal. If a bot or an assistant can attach a kernel oops trace, syzbot report or bisect result that explains the failure, that is great. But if a link is just a pointer back to the patch email or a landing page without diagnostic even, it’s negative utility; it just costs maintainers brain cycles for no return.

The anatomy of a good link

Plenty of things in kernerl flows canbe identified as pure links. A link to mail thread in the mailing list that gets the NAK and the newer approach to it also helps reviewers to understand what changed? A reference to a kernel bug tracker entry with steps to reproduce and implicated hardware gives the patch a concrete user visible base. A syzkaller/syzbot ID containing the crash, kernel version, and public triage is gold. A reference to a vendors end of life advisory complete with root-cause descriptions too is fair game when it explains a real-world failure mode.

On the other hand, don’t link to a generic project page, your fork’s top-level repository, or the same email thread without context. If the link doesn’t give new information—logs, traces, benchmarks, perf regressions, design discussions—omit it and invest in the commit message.

Maintainer Time Is Precious — and Quantifiable

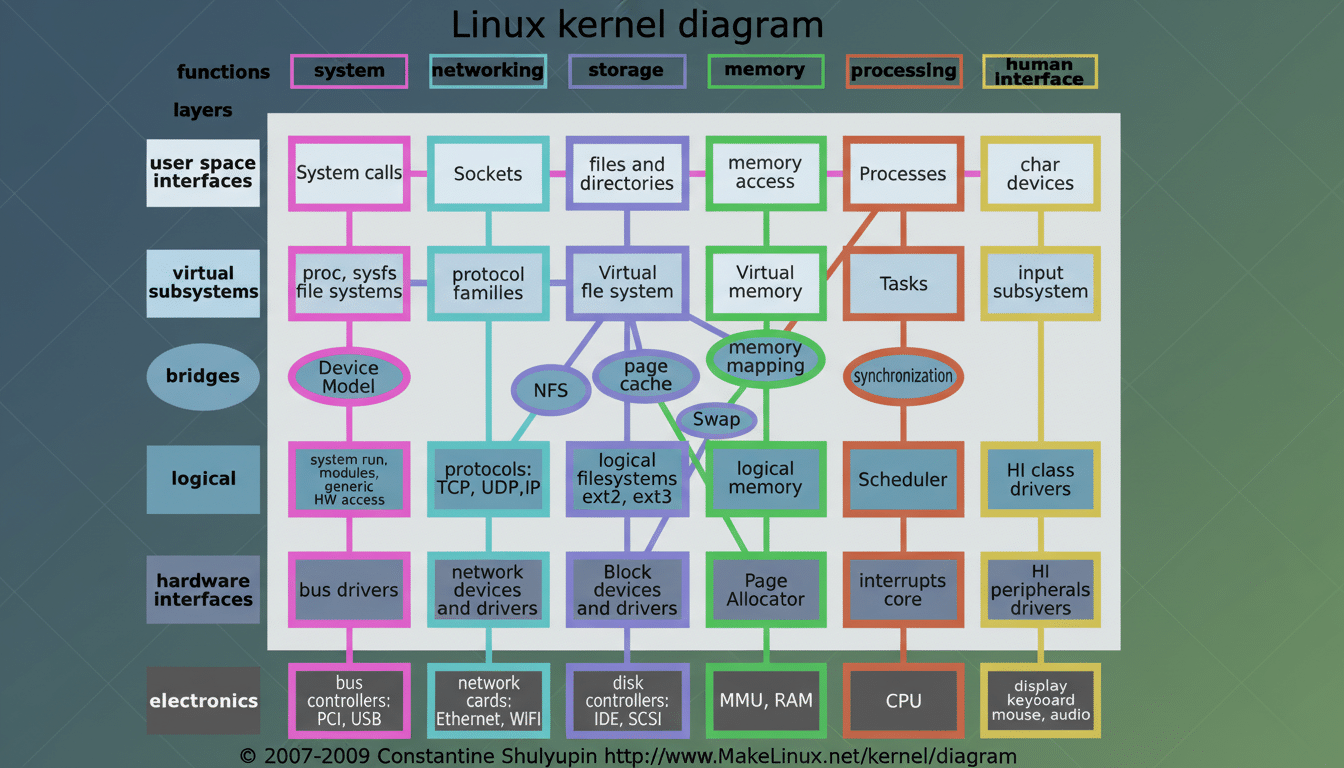

The Linux kernel is a large, fast moving codebase of almost 40 million lines of code with thousands of developers and maintainers responsible for the code within the kernel.

Public analyses by the Linux Foundation, and community reports over several years, indicate that every merge window has already seen on the order of tens of thousands of non-merge commits from around a thousand developers. For each minute a maintainer spends clicking through unnecessary links, that’s multiplied over subsystems and reviewers and turns into a genuine tax on velocity.

It also erodes trust. A patch which defers its reasons to an empty link sounds as if it were produced by a script. Maintainers aren’t looking at your style when they review your code; they’re judging if your code is safe to merge. A sharp and engaged reason is better than placeholder references any day.

How to live up to the bar Torvalds has set

Begin with a clear explanation in the commit message: what broke, how the breakage was found, how this commit fixes the problem, and what other possible failure modes remain. If you add a “Link:”, please avoid using it unless you feel you must—it shouldn’t be necessary in order to understand the message (and if it is necessary, it likely should be in the message). Prefer syzbot reports as a source of traceable stuff (not just strings) as opposed to vague references.

Use the trailers that maintainers actually rely on: “Fixes:” for the commit that introduced the bug, “Reported-by:” for the reporter, “Tested-by:” to record validation, and only then “Link:” with a pointer to other context. Do your standard checks, get at least one subsystem review, drop any autogenerated fluff before posting to the list.

AI is not an alibi for 2nd-rate patches

It’s worth doing all of these and assisted tools can help, but they don’t free authors of responsibility>

If the AI or the platform integration inserts a link that doesn’t contribute to help a reviewer to understand the bug, remove it. Torvalds’ message is simple: Don’t outsource judgment. In the kernel, clean is a feature, dirty is a bug.