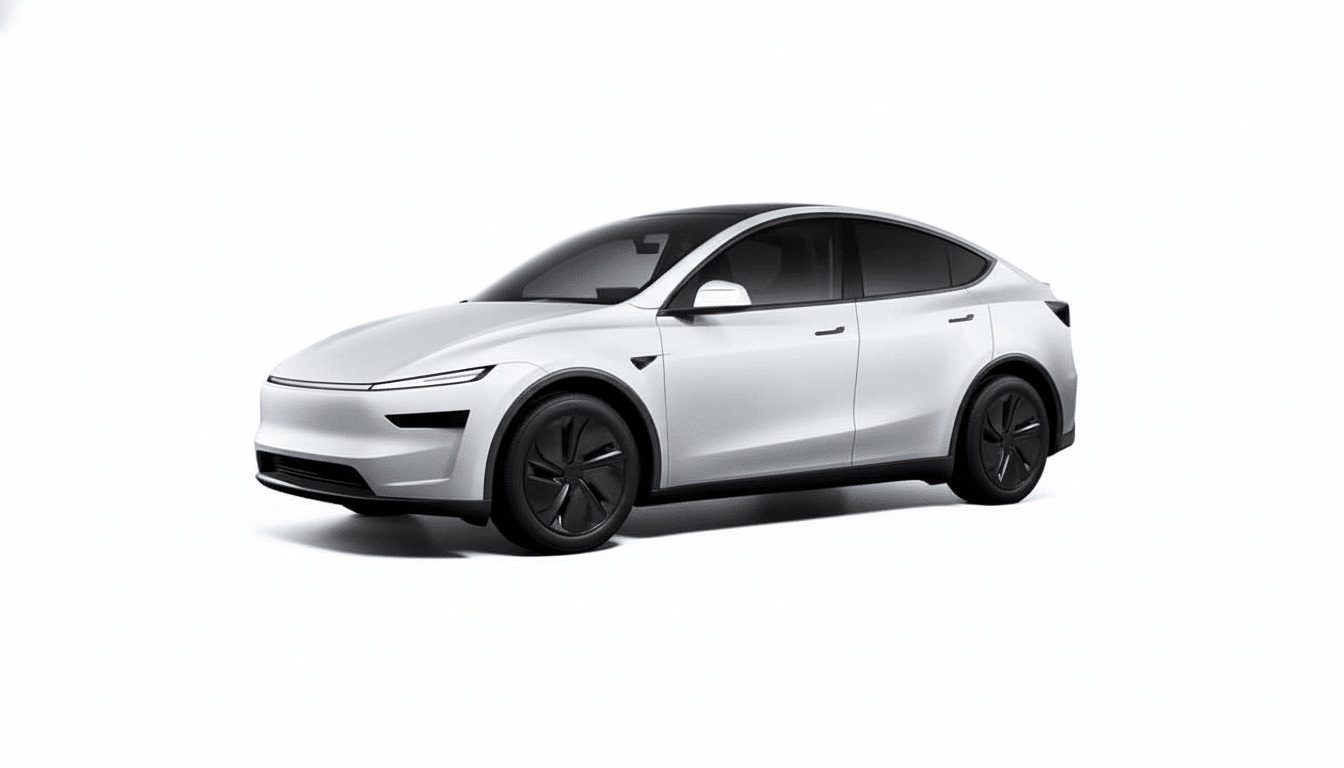

U.S. auto-safety regulators have launched a new investigation into Tesla’s Full Self-Driving driver-assistance software, looking at whether the system plays a role in traffic-law violations on public roads. The probe involves approximately 2.9 million vehicles containing software capable of running FSD, a broad set that underscores the technology’s penetration and the risks it poses to drivers, pedestrians and other motorists.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Office of Defects Investigation said it has compiled 32 reports claiming such unsafe behavior with FSD enabled — including Teslas running red lights, picking the wrong lane or going in the wrong direction while attempting to change lanes. Regulators are classifying the review as a precursor to action that may result in a recall if they find a defect with Takata airbags.

What Triggered the Probe Into Tesla’s FSD System

Investigators have documented 58 reports of FSD and traffic control enforcement, including 14 crashes and 23 injuries. In more than a dozen complaints, drivers said the car did not remain at a complete stop at a red signal or misread the state of the light in the interface. In six of the cases, vehicles were said to have entered an intersection on a red light and clashed with cross traffic.

Drivers also reported that the car would misjudge the available space, for example, starting a lane change into oncoming lanes. The agency also is looking at how systems perform at train crossings, an especially deadly setting where a misinterpretation or a failure to detect can be especially dangerous.

Tesla sells FSD as a highly advanced driver-assistance feature for which human supervision is always necessary. NHTSA, relying on consumer complaints and crash data, is investigating whether the design or operation of the system could lead to violations even though the driver himself has a legal duty to monitor the vehicle.

What Investigators Are Examining in the FSD Review

The review is focused on how FSD deals with traffic control devices, lane keeping, unprotected turns and grade crossings — as well as how safe it is considering the driver monitoring and human-machine interface cues in addition to other considerations. Regulators usually ask for details of actual events, the history of software versions and evidence that a system works as claimed — how it makes decisions, when control is relinquished and how it signals to an unengaged driver.

Since FSD is sent in over-the-air updates, investigators will scrutinize whether any recent software changes enhanced, reduced or left unaddressed unsafe driving behaviors. The agency suspects FSD might lead to behavior that’s in conflict with traffic safety laws, a fundamental query for any defect finding, The Guardian has reported.

Context matters here. One of the deadliest urban driving failures is to run a red light; The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety estimates that more than a thousand U.S. deaths each year are caused by drivers running red lights. At crossings, the Federal Railroad Administration logs thousands of collisions each year — and that’s assuming detection and compliance at a rail crossing is mission-critical to any driver-assistance stack.

Past Cases of Violating Safety Rules and Previous Behavior

NHTSA has repeatedly raised concerns with Tesla about its automatic-driving safeguards. A sweep recall in late 2023 forced nearly two million cars to add Autosteer supervision checks following a yearslong investigation into misuse of the feature. In an earlier incident this year, Tesla updated hundreds of thousands of vehicles with FSD Beta that were exhibiting dangerous behavior such as failing to make a complete stop and driving at inappropriate speeds through intersections.

In a separate investigation opened last year, regulators are examining performance related to FSD in low-visibility conditions following several accidents, one of them fatal. The National Transportation Safety Board has also faulted holes in driver monitoring and pressed for more guardrails around partial automation.

More recently, regulators sought answers after videos appeared to show driverless Tesla vehicles on the streets of Austin and breaking traffic laws. Even though Tesla says FSD is just a Level 2 system and demands an attentive driver, public demonstrations and user-shared clips work to further confuse consumers about the technology’s capabilities and limitations.

Effects on Drivers and Tesla if a Defect Is Found

If NHTSA were to find a safety defect, the fix would probably be updated software that you receive remotely — stronger enforcement of traffic signs, an improved logic for picking lanes and more rigorous checks for driver attention via the in-cabin camera. Examples of more depending on the direction and effect for owners are more frequent nags, faster disengagement, or tighter operational constraints in demanding environments.

For Tesla, the investigation animates the company’s fundamental thesis that vision-based autonomy can reliably negotiate dense, rule-bound urban spaces at scale. It can also heighten risks of exposure to insurers and state regulators, including motor vehicle agencies that track claims about automated features and on-road performance.

What Comes Next in NHTSA’s Tesla FSD Investigation

NHTSA’s procedure usually involves a Preliminary Evaluation, followed by an Engineering Analysis before any recall request. Timelines also vary widely; high-volume, software-driven systems can trigger speedier interim responses where they are considered urgent. Tesla is able to provide data, suggest software workarounds and challenge defect findings, though it frequently releases updates alongside agency investigations.

Good, bad or no, the bottom line is simple: partial automation must reliably follow traffic laws in every situation, and any behavior that increases the likelihood of blowing a red light or choosing the wrong lane will be subject to extreme regulatory scrutiny. As the investigation continues, owners should remember to understand FSD as a driver-assistance feature — not an autonomous one — and be ready to assume control at any time.