On a wind-whipped chunk of California coast with zero cellular bars, I made a WhatsApp video call from a regular smartphone — no satellite phone, no ugly antenna. The gadget latched on to SpaceX’s direct-to-cell Starlink satellites, and within seconds I was chatting via video face-to-face — sending photos and starting even a brief live stream or two over X. Grainy? Absolutely. Mind-blowing? Even more so.

That is the promise of T-Mobile’s cellular Starlink: Take dead zones and make them, if not exactly shine with a surfeit of data, work well enough for basic tasks. It’s not fiber-in-the-sky, but it is already practical for real communication in locations where phones are normally just paperweights.

How to Turn a Regular Phone Into a Satellite Phone

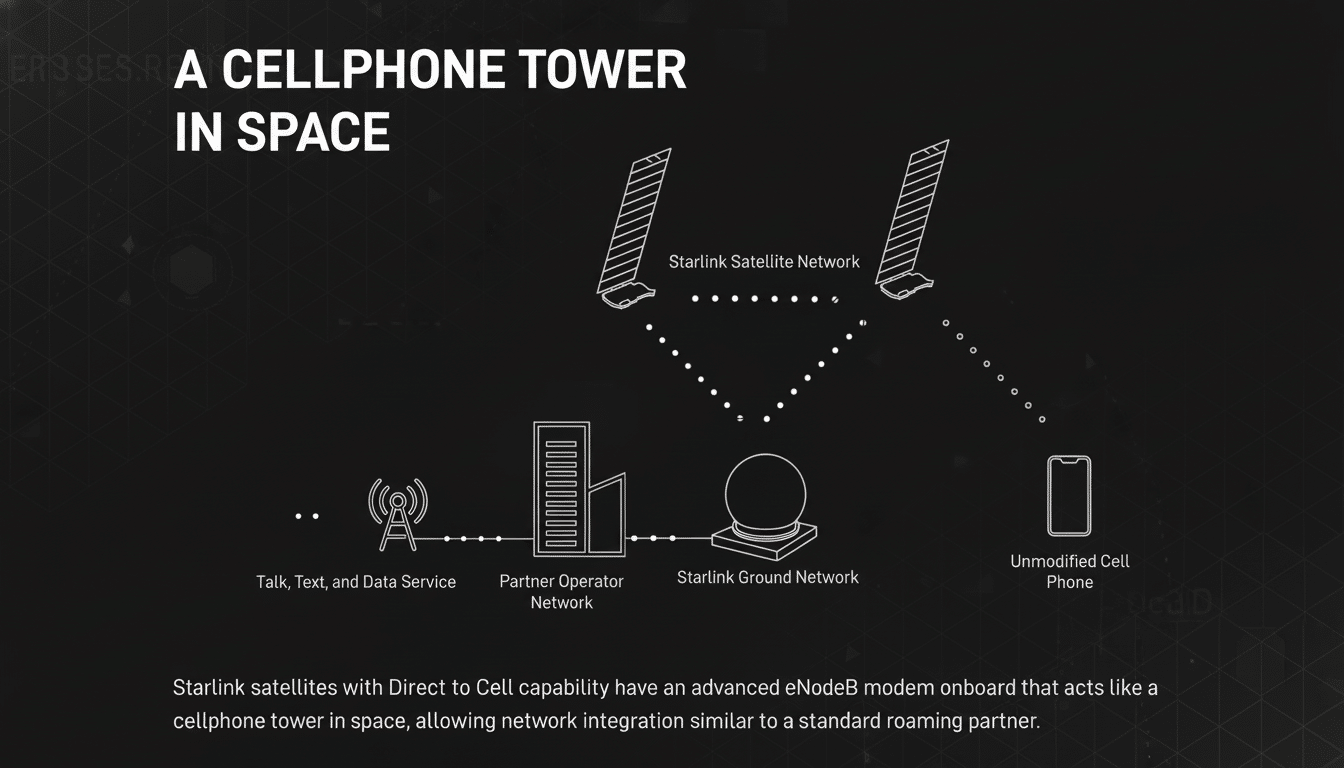

Starlink’s “direct-to-cell” technology relies on satellites in low Earth orbit to serve as so-called cell towers in the sky, with the signal bouncing back to handsets across frequencies that T-Mobile is already licensed to use on land. The satellites fly a few hundred miles above the planet and hand off your phone as they pass — quite a bit, because handhelds have small antennas and restricted power budgets.

Underneath that, it fits the wider 3GPP Release 17 trajectory for non-terrestrial networks, adapted for consumer phones. Initial service SpaceX has publicly described is text-first with tightly managed low-bandwidth data, and that’s what it looks like today: small bursts for messaging (a message or photo here), mapping pings, weather pulls — and, remarkably, low-res video calling if the link is good.

What I Saw in the Field During Direct-to-Cell Tests

From a known dead zone just south of San Francisco, I initiated multiple WhatsApp video calls with the Google Pixel 10. The majority connected on the first attempt. Resolution fluctuated between 144p and 240p, with intermittent frozen frames and brief audio cutouts. It would sometimes take seconds for a call to set up. A call broke at around three minutes, another extended beyond six, and a longer chat stretched past 10 minutes before I had the sense to ring off.

Plain messaging felt almost normal. Texts and photos would often immediately arrive on a second phone with terrestrial service. X loaded timelines, photos and short clips — slower and blurrier than usual but workable. I could even go live, although the streams I did were short and the app would crash occasionally in weaker signal times.

Maps and weather pulled down data, but routing was spotty when the signal dropped. Performance below trees was absolutely dire; think very light tasks only. The link worked laggily inside the car. Open sky matters. When the satellite indicator dropped to zero bars, all I could do was hold out for a pass overhead or a clear view of the sky.

Coverage Gaps and Why This Emerging Service Matters

Nationwide coverage maps, published by the F.C.C., continue to show significant gaps in mobile service across rural corridors, parks and coastal stretches. Direct-to-cell satellites will not usher in the end of 5G anytime soon, but they can go some distance to whittling down those “no service” moments that doom hikers, sailors, off-grid workers and drivers lost on distant highways. The jump from SOS-style texts to app-level data, even at low bitrates, is the difference between isolation and participation.

The capacity questions are real. Satellite beams have to be partitioned to serve a large number of users, and early service faces bandwidth limitations. SpaceX has claimed it purchased more spectrum from EchoStar and expects a drastic throughput increase with next-gen satellites and updated phone chipsets. That’s going to take time, more launches and ecosystem upgrades — but it suggests a clear ramp.

Devices, supported apps and the early service limits

Google’s Pixel 10 line was one of the first to enable app-level satellite data on T-Mobile. More phones will be added in waves, a recent carrier announcement suggests, and some iPhone models can request supported Apple apps like Maps, Messages, or Weather after downloading the latest software updates. It’s, above all, in the US that messaging support is really missing; there, more than anywhere else, iMessage and SMS are habits people use.

Conservative data policies should be the rule at first. Previous versions of the plan valued basic satellite messaging around $10 a month; app data expands on that, with long HD streams not in its sights. Think of this as a resilience bandwidth: enough for check-ins, navigation, weather, lightweight social media and short video chats when skies and satellite geometry align.

Test takeaways and what comes next for Starlink service

- It works. Actual video chats from infamously bad rooms felt dreamily bizarre and actually practical.

- Quality is early-stage. Get used to low resolutions, freezes and dropped sessions as the fleet of satellites orbiting overhead changes, and capacity waxes and wanes.

- Open sky is your friend. Signal is sapped by trees, canyons and cars. Short, purposeful sessions perform best.

- Experience will be decided by scale. Reliability and throughput should improve over time as more satellites are launched, more spectrum is used and handset modems get better. Monitor carrier and SpaceX progress, as well as FCC filings and 3GPP device roadmaps as the ecosystem develops.

By the numbers: satellite video chat from a pocketable phone just went from demo to doable. It will not be a replacement for your 5G plan, but it rewrites what’s possible where mobile networks disappear entirely — and that is a revolution hiding in plain sight above the horizon.