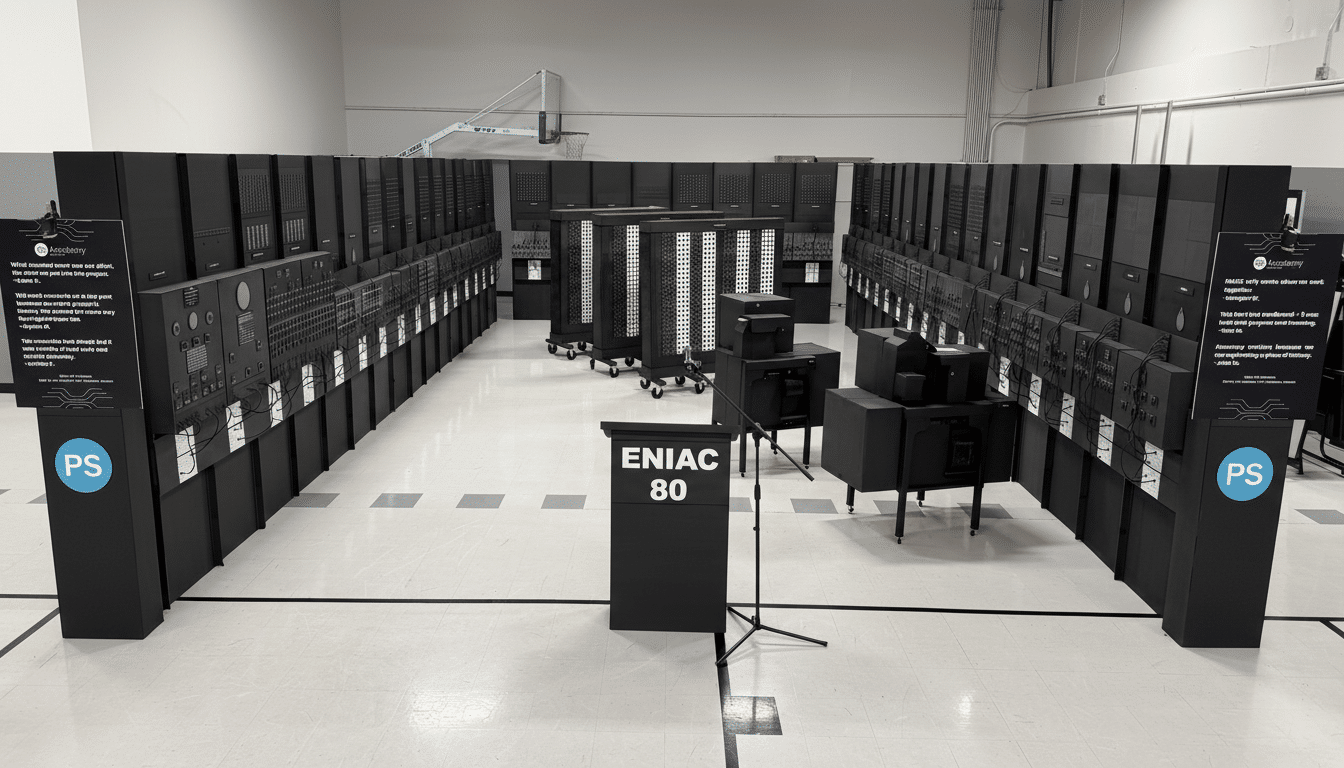

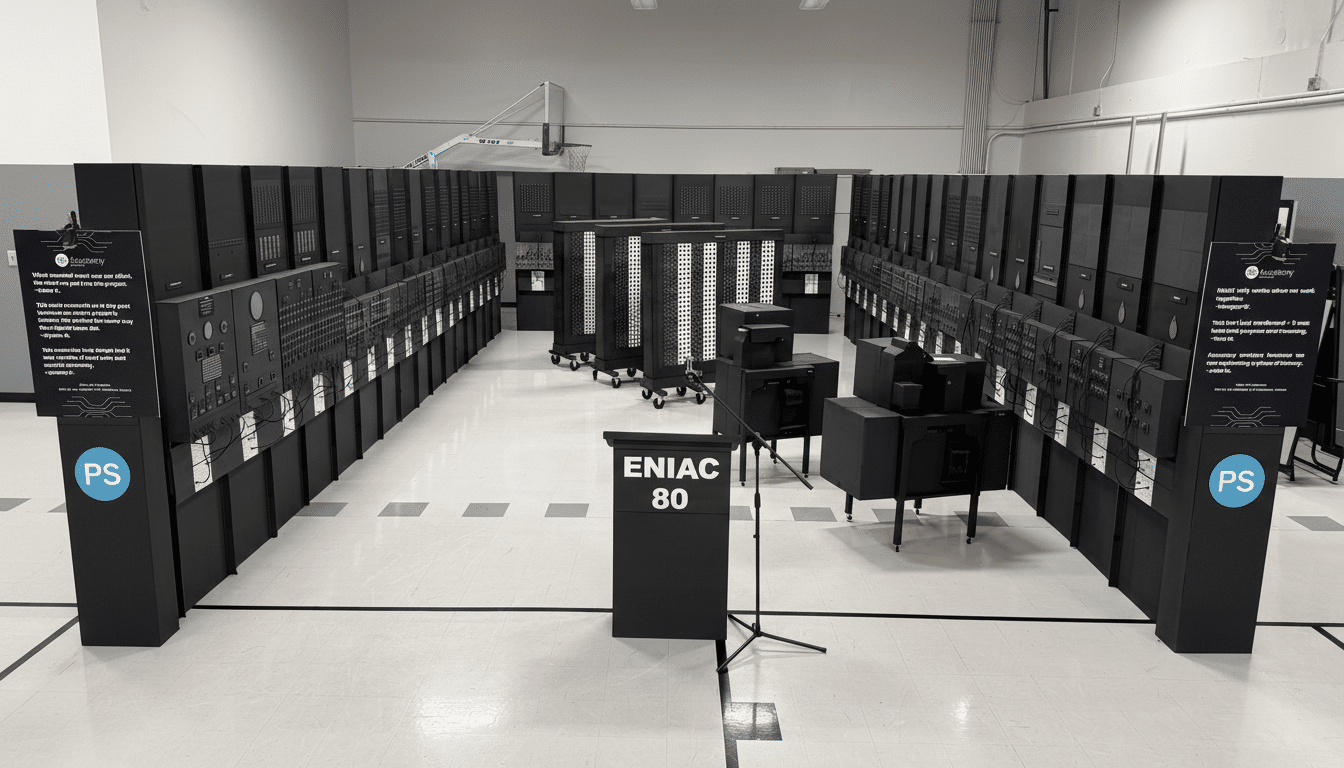

In a feat that bridges hands-on craft with computing history, 80 autistic students at PS Academy Arizona have built a full-scale replica of ENIAC, the room-filling machine widely credited as the world’s first general-purpose electronic computer. The team spent nearly six months fabricating 22,000 custom parts and assembling them with 1,600 hot glue sticks, unveiling an immersive, walk-by exhibit that glows with hundreds of LEDs and even recreates the sonorous hum and relay clicks that once defined early digital computing.

A Room-Size Reminder Of Computing’s Origins

ENIAC—short for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer—debuted in 1946 as a US Army project to accelerate artillery firing tables. According to the Computer History Museum and archival materials from the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School, it spanned roughly 1,800 square feet, weighed over 30 tons, and drew around 150 kilowatts of power. Inside were 17,468 vacuum tubes, 70,000 resistors, and millions of hand-soldered joints, all orchestrated to run thousands of operations per second, including up to 5,000 additions per second.

While earlier machines like the British Colossus and Konrad Zuse’s Z3 broke ground in computation, they were either special-purpose or electromechanical. ENIAC’s hallmark was flexibility: it could be reconfigured to tackle weather prediction, Monte Carlo simulations, and early nuclear feasibility studies for the US government—an ancestor of the reprogrammable computers we use today.

How 80 Students Built a Giant ENIAC Replica Exhibit

Reimagining a machine that once filled an entire room is as much a research project as a fabrication challenge. Guided by technology teacher Tom Burick, the students studied original patent drawings, Army documentation, and period photography to nail the proportions, panel layouts, and iconic cabling. They sought input from ENIAC historian Brian Stuart, consulted the descendants of co-creator John Mauchly, and worked with Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum, to validate details and avoid historical anachronisms.

The effort became a masterclass in precision and teamwork. Students designed and assembled panel facades, fashioned dummy tube banks, routed color-coded wiring, and installed LED arrays to mimic status lamps. The result is less a prop and more a faithful, full-size visualization of a machine that defined an era. It’s tactile, towering, and—importantly—accessible to anyone who’s only ever known computers as pocket-sized rectangles.

A Sensory Exhibit, Not a Functioning ENIAC Machine

This replica does not compute—and that’s by design. True ENIAC panels relied on thousands of power-hungry vacuum tubes, point-to-point wiring, and manual plugboard programming. Rebuilding a functioning version would demand specialized parts, high voltages, and maintenance headaches that even 1940s engineers struggled to tame. Instead, the students focused on the experience: lights that suggest activity, a carefully engineered soundtrack that evokes transformer rumble and relay chatter, and enough physical presence to make visitors stop and take stock of computing’s roots.

It’s unexpectedly effective. The sheer scale clarifies why early programmers—many of them pioneering women working at the Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory—treated computing as a spatial craft. Programs were configured across racks, cables, and switches; debugging often meant walking around the machine, tracing logic with your eyes and hands.

Why ENIAC Still Matters in Today’s Computing World

Stand beside a life-size ENIAC and modern progress snaps into focus. Today’s smartphones can perform billions of operations per second, sip a fraction of the power, and fit in a pocket. Yet the conceptual lineage is direct: modular units, memory, I/O, and the idea that software can reconfigure general-purpose hardware to solve new problems. As the Computer History Museum notes, that shift—from single-use calculators to flexible, electronic, reprogrammable systems—changed everything from science to commerce.

The project also shows how neurodiversity can be a strength in STEM. Students honed sustained attention, pattern recognition, and quality control across countless repeated tasks—wiring runs, panel alignments, and LED placements—while building confidence in their abilities. Educators often cite project-based learning for boosting retention and motivation; here, the evidence is tangible and 30 feet long.

Where to See the Full-Scale ENIAC Replica Next

The replica is currently on display at PS Academy Arizona, with conversations underway about a potential long-term home, including interest from the Computer History Museum. Wherever it lands, it’s a standout example of how to teach computing history in three dimensions—inviting people not just to read about innovation, but to feel it at full scale.

For anyone who has ever wondered how we got from room-sized switchboards to AI in a pocket, this student-built ENIAC offers the most persuasive answer: start by walking the length of the past.