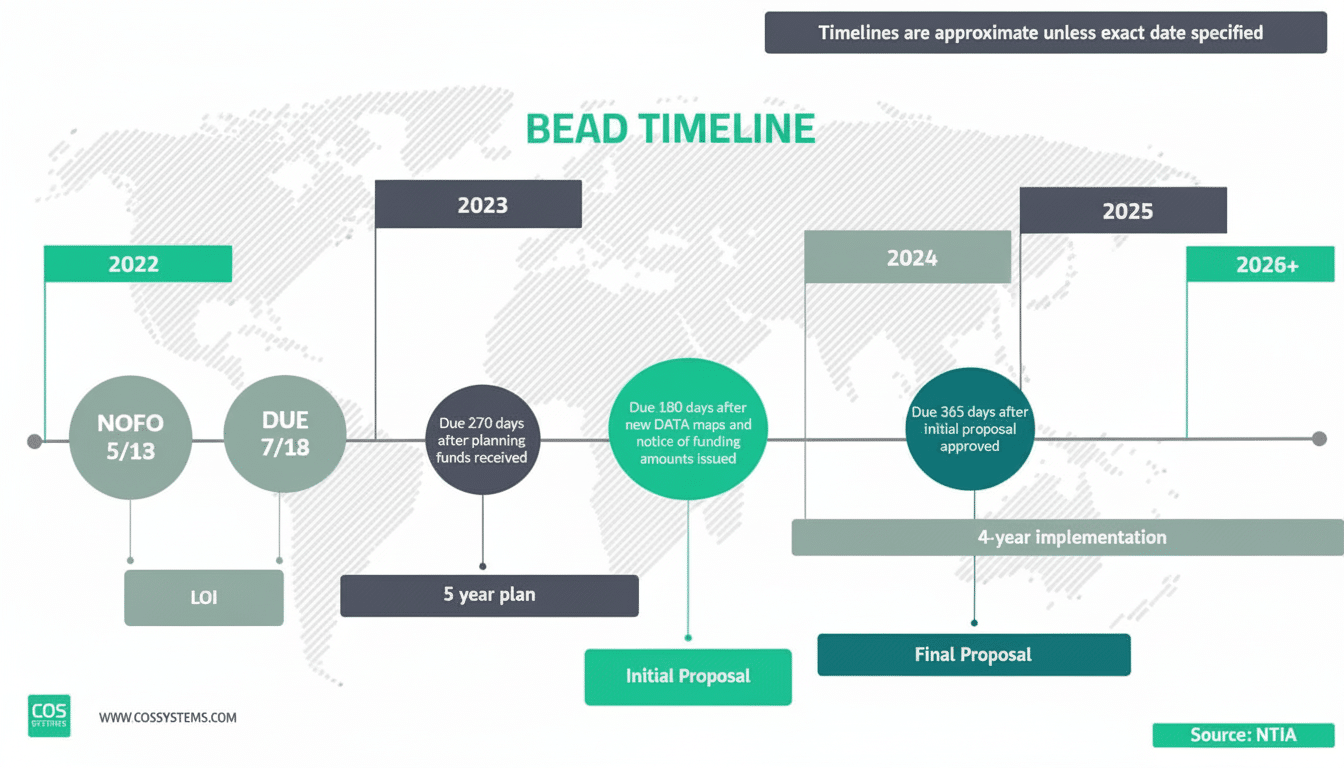

SpaceX’s Starlink is set to tap around $300 million in state plans from the federal Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, recipients of the aid that will provide service to some 200,000 hard-to-reach locations in the United States.

The anticipated awards are part of a policy change that allows states greater flexibility in funding “technology neutral” projects in areas with some of the highest costs to serve — a level so expensive that it may not be cost-effective to trench fiber or string up cable networks. A dozen states and territories have now filed plans that describe how satellite is part of the portfolio of new fiber deployment, according to filings from state broadband offices and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

How BEAD Dollars Are Being Spent

On approved plans to date, Starlink’s average support is roughly $1,470 per location. By comparison, fiber proposals in remote areas can quickly exceed $10,000 per passing once make-ready, pole replacements, permitting and miles of new plant are added to the bill. That gulf accounts for why states are mixing approaches, by funding fiber where density and economics find a happy intersection, and using satellites to shoot through intransigent holes on the map.

States are reporting that they are expected to leverage at least $13 billion in taxpayer savings, resulting from increased private matching, more competitive bidding and new innovative delivery options, according to NTIA. And unofficial totals from some industry analysts like Wes Robinson of Eastex Telephone Cooperative show it has obligated about 44% of dollars currently budgeted so far, returning or reprogramming billions for future use.

Why States Are Looking to Satellites

There’s a trade-off. Starlink typically provides 100–300 Mbps service with terrestrial-like latency (tens of milliseconds) that’s good for most household applications, not the symmetrical multi-Gigabit capability of fiber. But satellites can be launched quickly, without new middle-mile construction, and at a fraction of the cost per address in less densely populated territories. SpaceX has also indicated network upgrades aimed at moving toward gigabitclass throughput as new satellites and capacity are added.

Some critics, including a number of digital equity groups and a few fiber providers, contend that the subsidy of satellite services would lock in place lower-capacity infrastructure in rural communities that in the long run will need fiber. State broadband offices respond that the mandate is universal coverage within congressional budget limits, and that satellites are a low-cost “bridge” where fiber-to-the-home isn’t viable today.

Where the Money’s Going

Early state plans emphasize large Starlink allocations in areas of rugged terrain with substantial distances between homes. Ohio has set aside about $51.6 million for some 31,000 locations. Washington state aims at around $43 million to more than 27,000 addresses, and Wisconsin targets about $34.4 million to nearly 23,000 hookups. These totals are in addition to substantial fiber awards, and they mirror that state’s combination of cost, density and deployment risk.

In practice, the satellites are being hailed as gap-fillers—blanketing low-density census blocks not otherwise economically feasible to build fiber out to as scored by a criteria sheet (focused on cost per location, technical performance, and long-term operations).

The Competitive Landscape

Amazon’s Project Kuiper is also poised to attract significant BEAD funds — or at least $124 million to expand to at least 200,000 locations in more than a dozen states, according to program documents and state plans. Although Kuiper is in the process of building its constellation, demonstrations results released by the company boast peak downloads of 1 Gbps, further ratcheting up the pressure on incumbents and emphasizing its program’s technology-open philosophy.

Major terrestrial players — including AT& T, Comcast, Frontier as well as regional cooperatives — are in line for hundreds of millions of dollars to expand fiber. The ensuingcompetitive battles amongfiber, fixed wireless and satellite providers are likely to sharpen bids — not to mentionstretch tax dollars dramatically.

What It Means for Households

Term for satellite awarder under BEAD is to provide no-cost user terminals and installation for eligible locations and reserve adequate network capacity to support these locations. However, monthly pricing is no longer determined by states under the revised guidance, so affordability becomes a question of what providers offer and any complementary subsidies that individual houseHolds may be eligible for.

Suppliers will also be held to performance and reliability requirements, oversight of which will fall to state broadband offices and the NTIA, with milestones, reporting, and potentially clawback punishments. Funded solutions are expected to achieve low-latency goals and be capable of the same common use cases, such as video conferencing, remote learning, and telehealth.

What to Watch Next

Remaining state plans are in the process of receiving final approval and subgrant awards will nail down what specific projects to pursue and in what timeframe. Residents who are in the covered areas should hear directly from providers once their addresses are confirmed to be eligible even though installation windows will vary by provider, as well as by state processes.

For SpaceX, a $300 million or so slate would solidify Starlink as a mainstream tool in the rural broadband toolkit. For policy makers, the allocations represent a certain coming to wisdom: Use fiber where it pencils out, and trust satellites to close the last pockets of digital isolation without blowing the budget.