SpaceX is planning the next step in its Starlink direct-to-cell world service with a mission to beam “actual” high-speed internet right on ordinary smartphones and to do so at global scale. The company’s satellite policy lead, David Goldman, suggested the step-change would rely on new spectrum, a next generation of more capable satellites and widespread handset support — from where we are today with “text or very basic apps” to offering true broadband in your pocket.

From SMS to Mobile Broadband on Everyday Smartphones

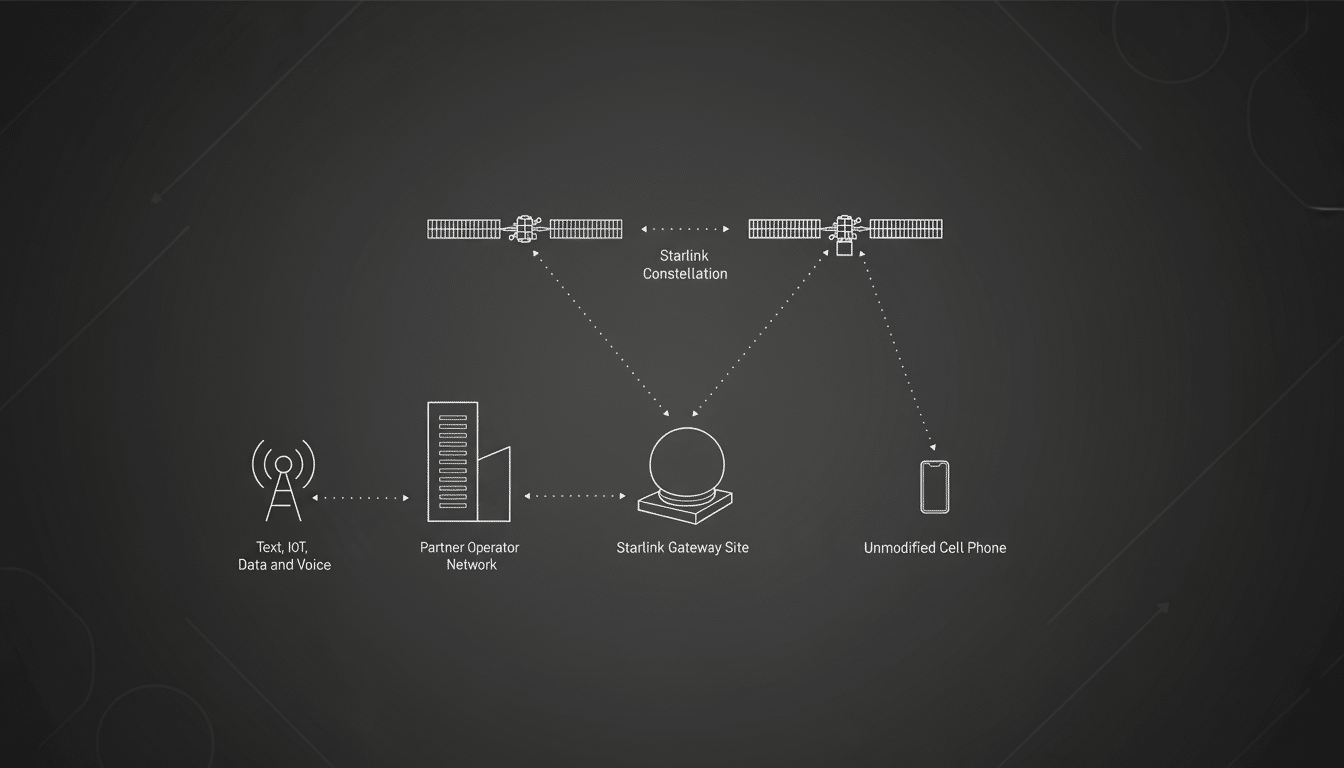

Starlink’s direct-to-device service advanced quickly from early messaging-only trials to LTE data on unmodified phones, with download speeds averaging about 4 Mbps in the field. The challenge has been to repurpose carriers’ existing spectrum so that the phones thought they were communicating with a tower very far away, not a distant satellite. That approach of having compatibility allowed SpaceX to strike roaming deals with T-Mobile and other operators, but also introduced heavy capacity restrictions and its own whitelists of apps.

Yet with those restrictions in place, the system has proven valuable in case of emergencies. Goldman cited large connections in Jamaica after a hurricane knocked out ground networks, pointing to satellite-to-phone as a resilient backstop when infrastructure crumbles.

The early lead, analysts say, matters. Recon Analytics commended SpaceX for establishing a deployment gap before competitors can reach commercial scale and anticipates app-specific limitations to be relieved somewhat as operators become more accustomed to the traffic profile.

New Spectrum and a New Constellation for Higher Speeds

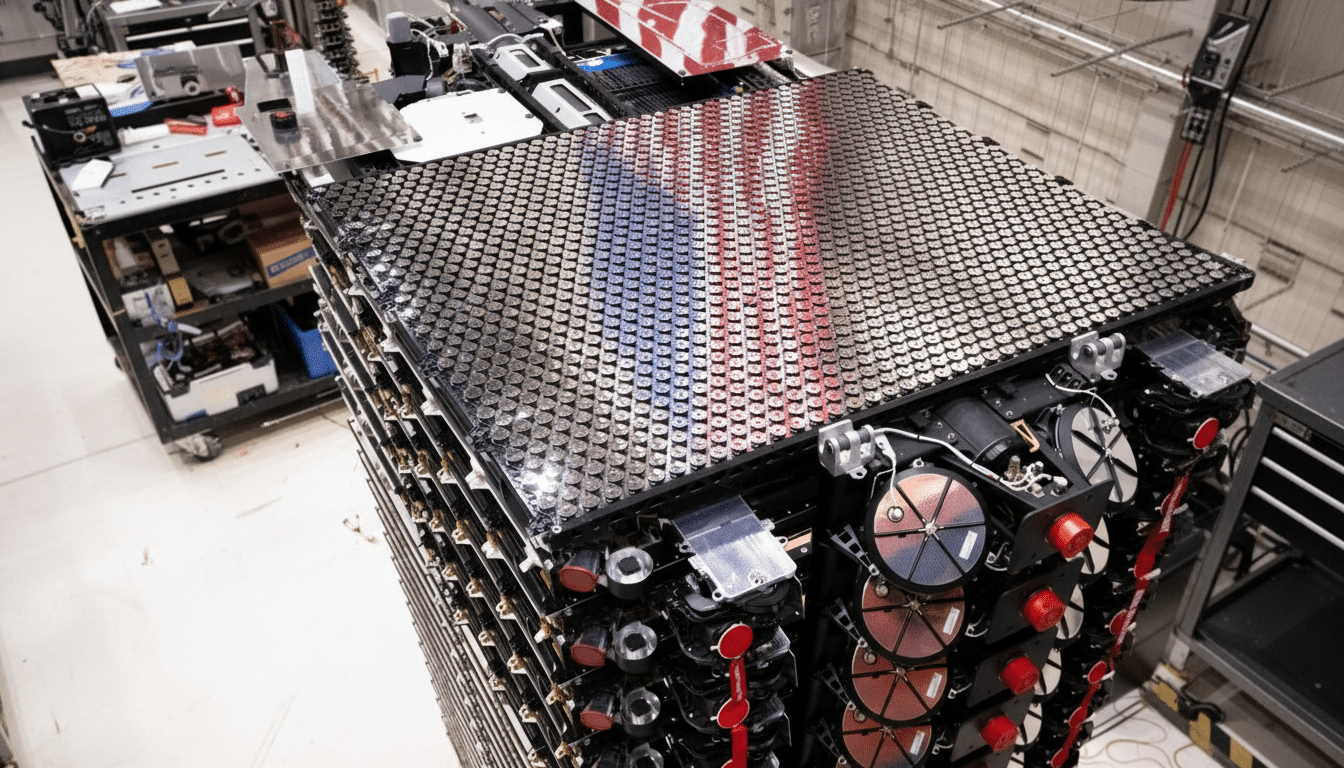

The promise of “high-speed” rests on two pillars. And first is spectrum that SpaceX is buying from EchoStar, much of which has been cleared in many countries for the links between space and Earth. Second is hardware: a third-generation Starlink fleet some 15,000 spacecraft strong that will inhabit closer orbits, carry more potent payloads and slice the sky into smaller beams oriented with far greater precision.

New filings with the Federal Communications Commission detail the architecture and why it should scale. Path loss is lower at lower altitude; tighter beams put more energy in each user with fewer users per beam, while higher-power payloads enhance the link budget. And industry analyst Tim Farrar reads the move as a simple one: If you reduce the number of people sharing each beam, you increase per-user throughput.

SpaceX plans to fly these larger satellites on its Starship heavy-lift vehicle, which will transport around 60 of the spacecraft per mission to low Earth orbit. Though Starship itself is still in a phase of flight tests, the spectrum licenses associated with its EchoStar deal aren’t expected to even transfer for quite some time, giving SpaceX plenty of runway to develop and deploy the new hardware.

Phones Must Evolve to Support Satellite Connections

Not all of the frequencies in SpaceX’s plan are supported by today’s handsets. Some of the AWS-3 spectrum is generally compatible, but there is little support for AWS-4. Goldman also forecasted that the essential bands will be added to mainstream handsets over the next few years. The latter will come with the need for buy-in from leading manufacturers — just one holdout can delay coverage ubiquity — and careful RF design to handle satellite link budgets alongside terrestrial 5G radios.

Borders add another wrinkle. Since neighboring countries allocate spectrum differently, Starlink has to turn down power near the borders to reduce interference — and limits service just where cross-border coverage would be most needed.

Can Satellite Keep Up with City and Indoor Speeds?

Expectations need calibration. Analysts warn that physics and capacity economics still heavily favor rural and remote areas over densely populated cities, even with new spectrum to use and thousands more satellites in orbit. Indoor performance will struggle as well — walls and low-elevation angles are unforgiving at satellite distances.

Ookla’s data provides some context: major-carrier users spend just 2.79% of their device time not connected to a cellular network. That means the flash points are small, momentary gaps rather than all-day satellite reliance. In that world, direct-to-cell is a universal safety net and a primary connection for all of the places that fiber and macro 5G won’t get to for years — if they ever do.

That said, if handsets and spectrum come together, the architecture could enable a fuller mobile offering. Recon Analytics reports that SpaceX is laying the foundation to package satellite coverage with terrestrial partners — or even launch its own hybrid service — down the road when device support and capacity mature.

Rivals Emerge and SpaceX Refines Its Regulatory Strategy

Competition is forming. AST SpaceMobile, which AT&T and Verizon are backing with an investment in satellite roaming, has launched only a few production satellites to date and is shifting its focus toward large second-generation spacecraft. Analysts have cast doubt on its timelines and capacity, but the company keeps government business including Department of Defense contracts — and is a non-SpaceX option that carriers may desire for supplier diversity.

For SpaceX, the road to “real” high-speed direct-to-cell seems like a relay of regulation and engineering. Get hold of globally harmonized spectrum; deploy a vast, more powerful constellation; convince handset makers to support the right bands; and demonstrate that the network can deliver not just messages and some apps but open internet access at meaningful speeds.

If all goes as planned, the experience will be indistinguishable from being on a terrestrial network in many places — coverage appearing out of nowhere on what used to be an uncovered portion of your phone’s status bar. And that, more than headline speeds, is the breakthrough that might finally change what it means to have signal wherever you are.