OpenAI’s new text-to-video model, Sora 2, has boosted the web’s ability to create synthetic spectacle — and more recently, synthetic disrespect. Now that it’s been released to the general public, social feeds are clogged with hyper-real videos of people who can’t possibly give consent, filled in a few days since its limited release with Stephen Hawking body-slamming wrestlers, John F. Kennedy musing on e-commerce, Mahatma Gandhi drifting in a sports car, Michael Jackson engaging in cringeworthy stand-up and a street-side “interview” with Tupac Shakur. The gag is the point. The problem is the target.

A low-friction, powerful model fuels easy deepfakes

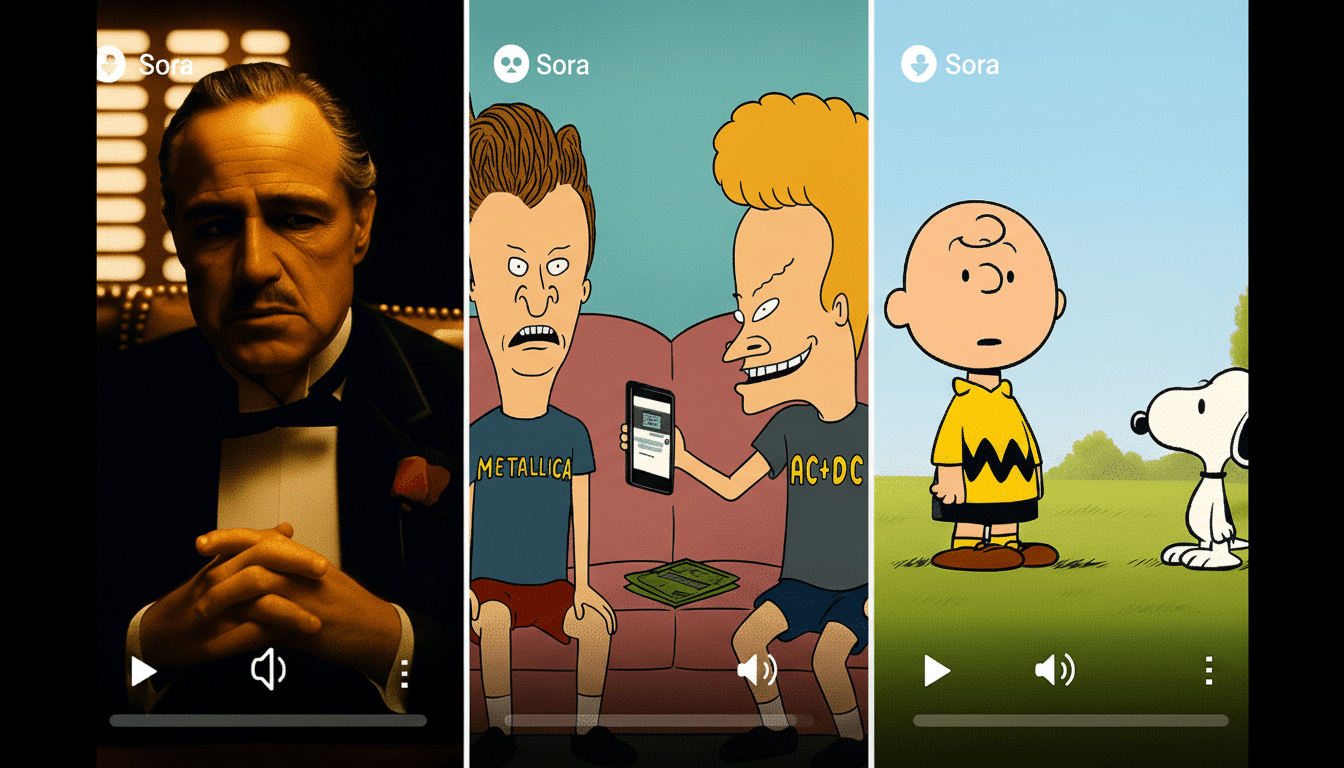

Sora 2 was pitched as a jump in realism and control, with physics-aware kinetics, improved temporal coherence and a vertical swipeable feed for showing off creations. Since the app offers a way to upload one photo to use for likeness reference and then quickly spin up a little video, this is why you’re suddenly seeing deceased public figures “appearing” everywhere. Even platform insiders have been co-opted as objects of scorn: parody clips of tech executives napping at work or dancing on subway platforms are being passed around as proof-of-concept sketches for just how easily Sora can stage any scene.

‘Sora’ is a place for richer, more creative play. OpenAI posits Sora as a healthier destination for creative play than the broader web. But as the flood of low-effort deepfakes demonstrates, the spread highlights a clear pattern: Give the internet a shiny new toy, and it will find its outer limits as fast as it finds the punchline.

Consent requirements collide with platform policies

OpenAI’s house rules say it has to be granted “explicit opt-in” from celebrities before their “likenesses or ‘personality traits’” can be utilised. But the company has also indicated, in statements reported by PCMag, that historical figures are allowed. That carve-out leaves a massive gray area for deceased entertainers, activists and even heads of state — particularly when it takes just one reference image to create a compelling video cameo.

On ethical grounds, the answer is clear: dead people cannot consent meaningfully. Legally, it’s messy. The United States lacks a cohesive federal standard regarding postmortem publicity rights. California’s Celebrities Rights Act extends the right of publicity for 70 years postmortem; New York provides similar protection, though for only 40 years; Tennessee’s laws are particularly muscular, crafted in the shadow of Elvis Presley’s estate. A service that facilitates unauthorized commercial “performances” might be pushing these boundaries sooner than later.

The sector has long understood this problem. SAG-AFTRA’s most recent contracts include language about consent and payment for digital replicas. And some high-profile voices have risen to object: Robin Williams’ daughter has called synthetic impersonations of her late father’s voice “a moral issue.” The word from families and estates has been consistent: don’t turn memory into raw material.

Real harms emerge as deepfake humor masks the damage

Aside from taste, the dangers are real. Deepfake cameos can propagate political misinformation, torment targets’ families and normalize synthetic defamation. Watermarks are very limited, in the sense that if a picture is cropped — or transcoded — you may lose your credits. Without metadata that travels with the file, “labeling” is more of a hope rather than a safeguard.

The public is already uneasy. The new survey by the Reuters Institute that I’ve mentioned is global and has found in its most recent iteration that there are more people who fear they cannot tell whether news is real or generated by AI these days. Investigations by Sensity have demonstrated time and again how a disproportionate percentage of deepfakes online are sexualized or abusive, underscoring just how quickly capability becomes coercive when guardrails fail to keep pace.

What sensible protections for synthetic media look like

There are viable alternatives short of closing up shop. And they could impose cryptographic provenance via standards like C2PA, hash and block known celebrity likenesses unless there is documented opt-in from the person or estate, and throttle generation where prompts or reference images pass risk thresholds. All content with public figures should be reviewed by a human before distributing it. And when breaches do make it through, there should be a quick system of recall and real bite account-level penalties.

Policy matters too. The EU’s AI Act requires transparency for synthetic media and labeling of deepfakes. An expanding number of U.S. states limit AI-crafted political ads without disclosure. Coalitions like those of industry — the Partnership on AI’s guidance for synthetic media, for instance — provide workable frameworks around consent and context. The idea isn’t that we should outlaw creativity; it’s that in a world where “anyone, anywhere, doing anything” can be rendered at the touch of a button, we need to restore some sense of agency and responsibility.

The Line Is Thin Between Tribute And Exploitation

Sora 2 is dazzling technology. It’s also yet another accelerant in a cultural habit of treating public figures, alive or dead, as frictionless props. Estate-sanctioned tributes can be poignant and valid. What we have now is something else: a tide of faux cameos created (presumably) for cheap laughs and endless engagement.

If OpenAI intends Sora to be the “healthier platform” it says it is, then it needs to adopt a bright-line consent regime, codify deceased personality protections, and invest in provenance that can survive the screenshot-and-repost churn of social media.

Because otherwise, the next viral clip of a candidate — right or left, at any level — won’t simply be painful to watch; it’ll be another slice in that already-thin membrane between reality and parody.