Sierra Space’s winged Dream Chaser has been reimagined since a NASA contract modification that removed guaranteed missions to the International Space Station, refocusing near-term goals toward a free-flying orbital demonstration instead of station resupply.

The shift forces a strategic pivot for one of the most eagerly awaited commercial spacecraft and adds new urgency to making a business case beyond NASA logistics.

NASA Contract Reset Requires a Strategic Pivot by Sierra Space

Dream Chaser was chosen as part of a NASA contract called Commercial Resupply Services along with SpaceX’s Dragon and Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus, all part of an overarching structure with an aggregate ceiling near $14 billion. NASA has, to date, obligated about $1.43 billion to Sierra Space, according to federal spending records for public procurements. With the latest modification, the agency now wants only “minimal support” for a standalone demonstration and will determine in time whether purchasing ISS resupply flights makes sense at all.

That reset is consequential. Space transportation systems are also incredibly capital-intensive, and most so far have relied on “anchor-government demand” to make the economics pencil. SpaceX’s Dragon and Falcon 9, for instance, received billions in NASA awards across both COTS and Commercial Crew from the space agency’s program documentation as well as the NASA Office of Inspector General. Being placed in the NGA queue means Dream Chaser has to show its worth to a number of additional customers much sooner than planned with no baseline manifest available.

From Station Resupply Runs to a Free-Flying Demo Flight

Instead of an early docking mission, Dream Chaser will fly solo as a free-flyer to demonstrate core capabilities: orbital operations, autonomous guidance, navigation, and control, reentry into the atmosphere, and runway landing.

The runway return at the Shuttle Landing Facility is a hallmark, offering gentler downmass conditions than any capsule splashdown for biological samples, precision hardware, and time-sensitive research.

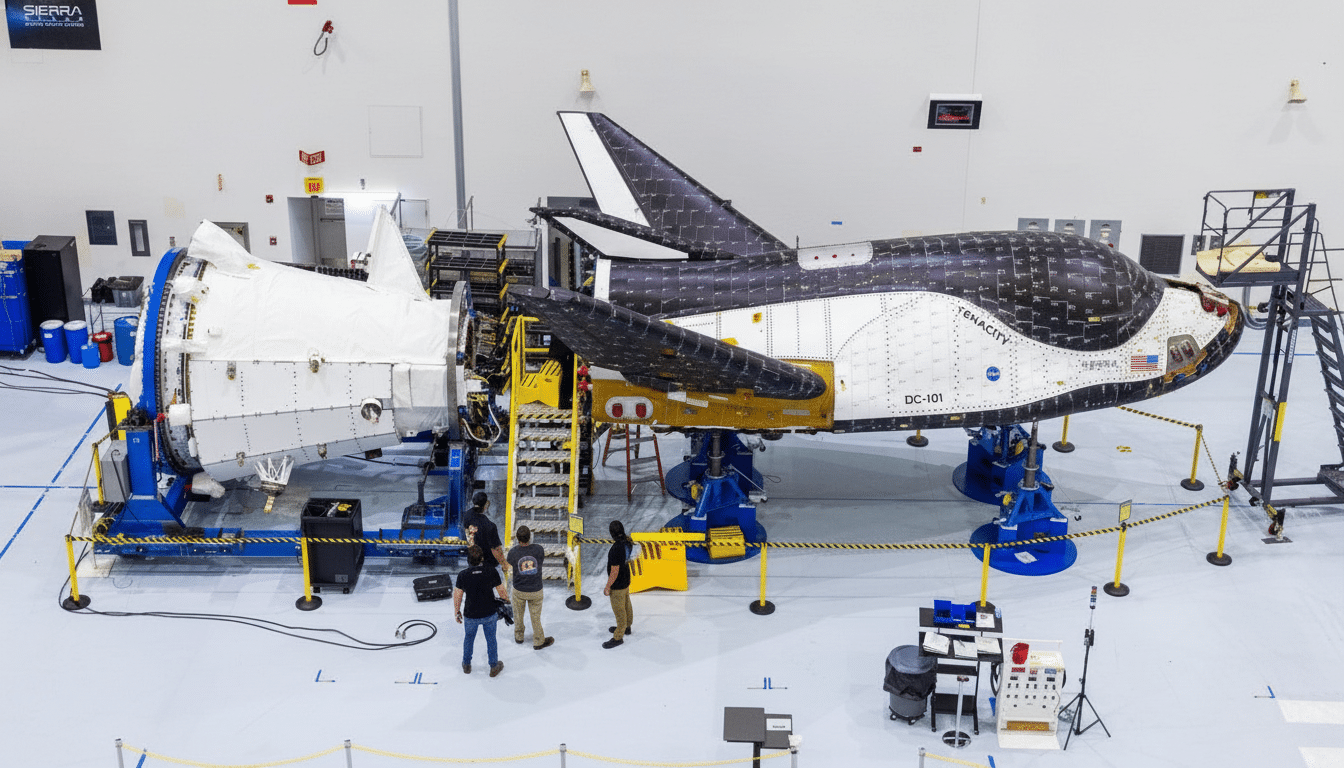

The lifting-body design of the spacecraft and its reusable airframe are at the core of the pitch. By teaming a winged vehicle design with a disposable service module (Shooting Star), Dream Chaser brings waste down, hosts payloads on-orbit, and carries large quantities of cargo up, while still returning sensitive experiments to the standard runway. Sierra Space has already reached significant milestones such as environmental testing at NASA’s Neil Armstrong Test Facility, which, Kurz said, shows the program is technically mature even as the mission profile changes.

In Pursuit of Markets Beyond the ISS Program’s End

With the ISS program winding down in the latter part of this decade, Sierra Space is pushing to position Dream Chaser for post-ISS demand. On the civil side, the company is a primary partner for Orbital Reef and one of NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations in a program that NASA OIG recently stated was facing schedule pressure. Other private stations, including Starlab and smaller outposts being developed, indicate a market where runway-return logistics and hosted payload services might have a place to shine.

Defense applications offer another path. The U.S. Space Force and other national security agencies have focused on responsive space, quick retrieval of materials, and an on-orbit test capability. Some sort of reusable, runway-landing spaceplane could help with experimentation, ISR tech maturation, or delicate component returns too fragile to fetch over water. Sierra Space leaders have described the switch as a chance to reconfigure Dream Chaser for an array of different mission profiles aimed at supporting national security objectives, according to recent company comments.

What Reinvention Will Require for Dream Chaser’s Future

To transform flexibility into contracts, Sierra Space will need to get three boxes checked lickety-split:

- Fly safely

- Demonstrate the speed of turnaround

- Drive per-mission costs down through reuse

The free-flyer demo can de-risk avionics, thermal protection, reentry dynamics, and runway ops — data points that commercial station developers, research customers, and defense buyers will mull before agreeing to a manifest.

Operationally, runway return is only part of the differentiator and needs to be matched with reliable upmass, predictable schedules, and on-ground cadence that looks more like aircraft than bespoke space missions. The company’s integrated approach — reusing an airframe along with a service module capable of hosting payloads and burning up waste — could simplify operations if Sierra Space can establish refurbishment timelines believably and at a competitive price.

For NASA, the new stance mitigates short-term risk yet allows it to keep an option open on a unique capability.

And if Dream Chaser hits its demo, the agency gets an additional complementary logistics mode: a winged vehicle that adds to capsules and freighters the ability to return as though it were landing on a runway. If it fails, the commercial and defense rotations may yet support a niche for a reusable spaceplane while most orbital transport is capsule-based.

Sierra Space came into the decade with deep pockets — it has raised more than $1.4 billion in a marquee round, according to company disclosure sent to investors — and a marquee spacecraft that caught the public’s imagination. The difficult part now is not so much in the envisioning but in the execution, at speed. Dream Chaser’s rebirth is in progress; the marketplace will only value proof, not potential.