A planet with no star to call its own found a temporary home on Earth last year.

Astronomers have now estimated the planet’s weight, as well as other basic characteristics that describe it as a smaller and lighter sibling of our own giant planets in the solar system like Saturn and Jupiter. The measurement resolves a long-standing issue for at least one candidate “rogue planet” and demonstrates conclusively that it’s a planet, not an underpowered failed star.

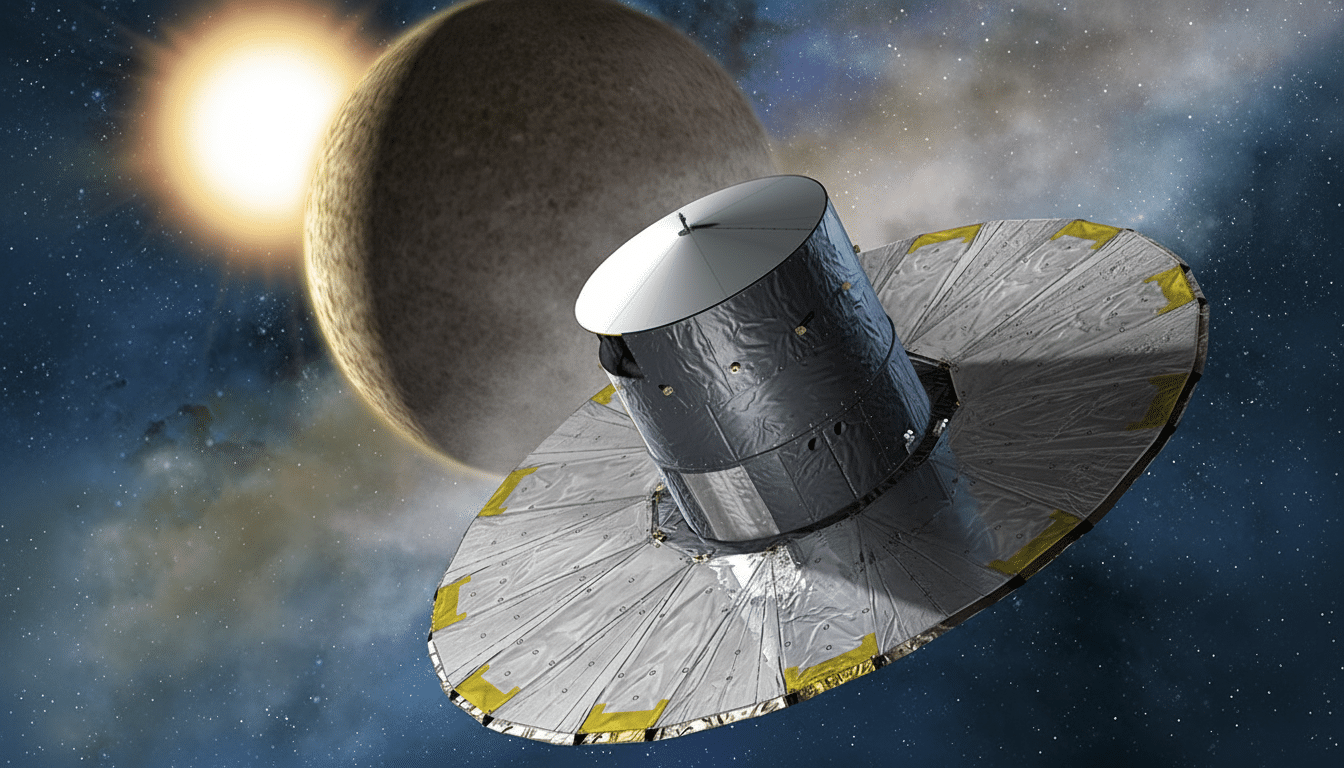

The team recorded a rare gravitational microlensing event with two perspectives — observatories on the ground and the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, cruising about one million miles from Earth. The light-curve timing, a difference of just two hours between the two observing sites, established the object’s distance and mass: around 22 percent that of Jupiter, some 9,800 light-years away with no host star visible.

A Rare Direct Weigh-In Of A Starless World

Rogue planets are practically invisible until gravity betrays them. When one passes in front of a more distant star, its gravity momentarily acts as a magnifying glass for that star’s light. These microlensing spikes can linger for hours to a few days and then disappear, taking almost no mass with them — unless there is a parent star left behind to anchor follow-up observations.

By watching the same two-day microlensing effect from both here on Earth and from Gaia, researchers were able to measure this parallax — a geometric effect similar in nature to human depth perception. The second “eye” breaks the mass–distance degeneracy that is familiar from single-site studies. The clean mass determination is akin to Saturn’s in our solar system, which Subo Dong of Peking University and collaborators describe in Science as crossing the threshold from candidate to planet.

As Gavin A. L. Coleman of Queen Mary University of London, who wrote a related commentary on the discovery, observed, most exoplanet techniques — even transits and radial velocities alike — are reliant on a host star. For starless drifters, microlensing is the only remotely possible way of finding them, and parallax is the entrance for having any hope of weighing them.

Saturn-Class Mass Changes the Picture for Planets

Objects that are more massive than Jupiter by a few times can form in isolation, as puny stars that fell short on growth, and become brown dwarfs. A Saturn-class body, however, is far more likely to have formed in a natal disk around a star. That suggests it had a violent past — whether being scattered by sibling planets, passing close to another star, or gravitational business earlier in its chaotic evolution as a planet — that cast it into interstellar exile.

This verified mass thus adds further evidence in favour of the fact that many a true castaway planet would exist within this galaxy. In dynamical runs, planet–planet scattering frequently ejects one or more planets even in systems with giant planets on unstable orbits. The new result provides an essential data point to tether those models to reality.

How Many Rogue Worlds Are There in the Milky Way

Wide-field surveys, e.g., OGLE, MOA, and KMTNet, identified dozens of short-timescale (few-day) microlensing events that are consistent with unbound planets — although most of the masses have so far been inferred statistically. Early analyses indicated Jupiter-mass free-floaters might be almost as abundant as stars, although later results using the OGLE data — which Mróz is a part of — suggested fewer rogue Jupiters and perhaps a tilt toward lower masses. In any case, estimates differ by an order of magnitude, and the census is still in dispute.

The direct weighing of a Saturn-mass drifter removes the question mark between “planet” and “brown dwarf” for planet-like objects with no associated star. With hard-edged masses, astronomers may begin to map an actual rogue-planet mass function and determine if ejection is the typical epiphenomenon of planet formation or a less-common result.

What Happens Next for Rogue Planet Hunting

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will revolutionize this field by conducting a high-cadence microlensing survey toward the galactic bulge. Roman’s fine cadence and coincident ground undertaking should record thousands of microlensing events and, more importantly, provide parallax measurements for many — thereby discovering hundreds of floating worlds spanning a wide range of mass.

Complementary campaigns with ESA’s Gaia and future astrometric missions will extend the parallax baseline, while networks like KMTNet and OGLE ensure 24/7 coverage. Together, such a network might push detections down to Earth-mass rogues; OGLE already reported a tantalizing candidate at that scale. If such worlds are common, that would mean young planetary systems commonly eject one or two planets as they relax into long-term stability.

For now, the Saturn-sized loner serves as a rare, robust benchmark. It cements the idea that at least some galactic drifters in the Milky Way are bona fide planets — created in a star’s glare, but doomed to roam without one.