I saw a robot vacuum put down two wheels and run on upended legs on a staircase, lifting its body off the floor to go where it pleased. This wasn’t a lab prototype behind glass. This was a live demo at CES, and the machine in question was Roborock’s Saros Rover — a consumer robot that is capable of literally cleaning its way up and down stairs.

A robot vacuum designed to work the stairs

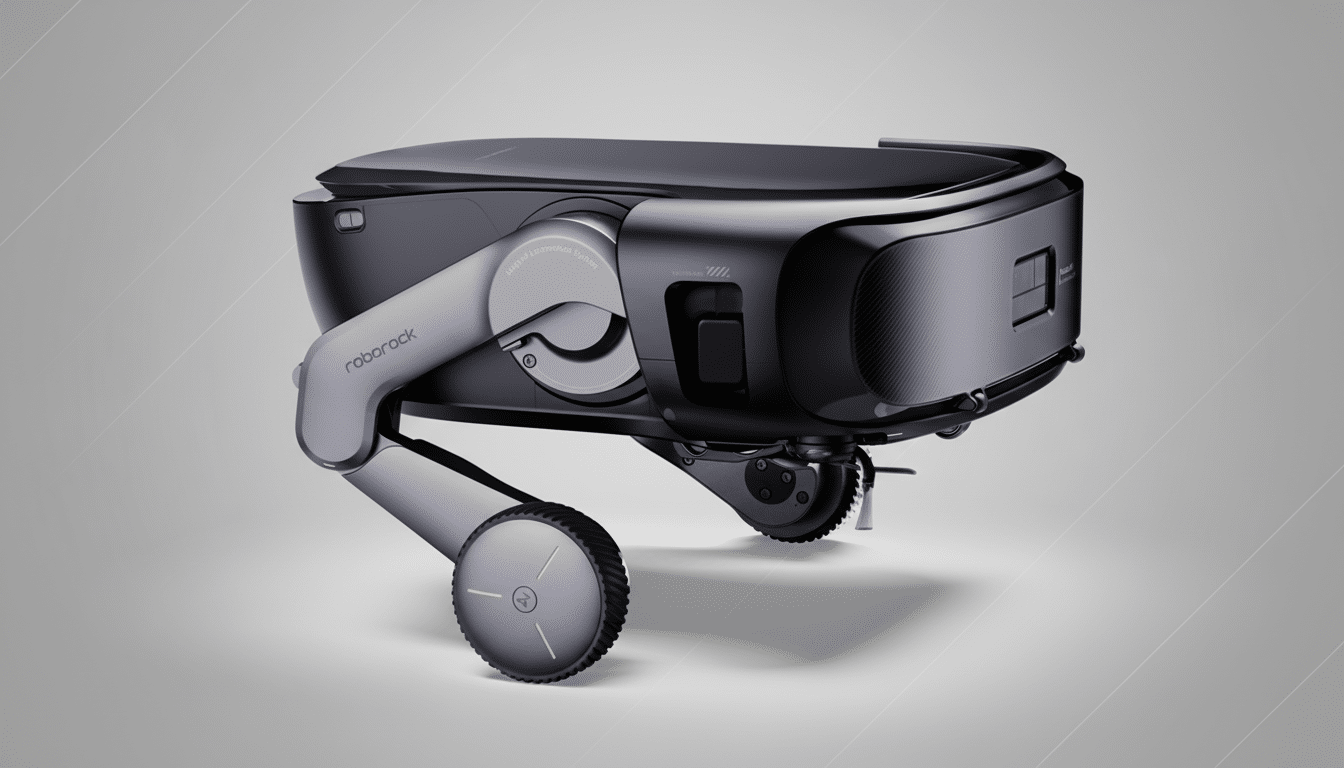

Roborock calls the construction a wheel-leg architecture: The drive wheels are located at the ends of collapsible legs, which extend to raise the body about 11 inches off the ground. In practice, it approached a standard staircase and stretched itself to reach the next step, against which the robot set its leg, maintaining its weight there and, from this, pushing its own body up. It stopped at each step to vacuum, then it did the same again — with no human handoff necessary.

The company says independent leg control allows the Rover to tilt, counterbalance on uneven surfaces, come to sudden stops, and make tight turns. The behavior seemed intentional as opposed to perfunctory: controlled ascents, cautious descents, and tweaks in posture that indicated it was responding to geometry rather than following a scripted routine.

Why stair climbing is important for homes

Stairs have been a robot vacuum’s equally undisputed “no-go zone” since the category launched. All these models map more than one story, yet you still have to transport them between floors. For a lot of households, that’s a deal-breaker. According to the National Association of Home Builders, about half of new single-family homes are two-story or more, and existing housing inventory is similarly proportioned throughout a wide range of regions. If a robot can’t master stairs, it can’t automate an entire generic home layout.

Which is perhaps why the demo felt like an inflection point. Consumer robotics has pushed out incrementally better suction and smarts around obstacle avoidance; self-emptying docks are a recent exciting development, but mobility has stubbornly languished. A robot that handles stairs and bridges the last floor transition could take the last big “but” off of the smart home vacuum pitch.

The science behind wheel legs for home robots

Robots with wheels for legs aren’t a new area of engineering research; platforms like ETH Zurich’s Ascento and work chronicled by IEEE Spectrum have suggested that adding a jointed leg to a wheel can allow it to efficiently roll as well as step around. The Saros Rover includes that idea in a crossover household appliance, which combines leg action with AI-based perception.

According to Roborock, the Rover integrates motion sensing and 3D spatial information — which usually translates into a mix of inertial measurement, odometry, and depth sensing for precise mapping. Control is nontrivial: to get to the nosing of a step, the robot must position a wheel with millimeter-level precision, maintain traction while raising the other side, and actively control for pitch/yaw of its body. On fiber carpet treads, contact forces change as the fibers compress and rebound — something pure wheel bots never have to deal with.

What I saw on the CES show floor demonstration

The Rover pulled up to a three-step rig at the pace of a casual stroll, took its measure, then sequenced its climb: unfold, plant, thrust sideways and up. It paused on each tread to suck up the dust before moving forward. The descent appeared even more orderly — legs arched out first, the body sank into position, and then wheels came afterward. The robot made a small lateral correction to avoid the obstacle placed on a tread, showing that it was not locked onto a single precomputed path.

Crucially, this wasn’t just some flimsy showpiece. The gait was reproducible and there were no handlers snatching it while in mid-stride. Roborock says the Rover is an active development program, not just a one-off prototype, though there’s no announcement of price or release window.

Caveats and open questions for real-world use

Real homes add complexity. The geometry of the stairs — that is, their rise, run, and profile of nosing — are very different. Rugs on treads can slip. Dust piles up along the edges and on the vertical risers — places where a circular robot might have trouble reaching, even if it could balance itself on them. Battery life is another matter: lifting a body over and over takes more energy than skipping along on flat floors, so multi-level cleaning may necessitate smarter scheduling or higher-cap packs.

Durability matters, too. Cyclic loads on leg joints, reduction gears, and torque sensors will experience application stresses rarely seen in most vacuums. Whether this becomes a staple appliance or a marvelous niche object will depend largely on how available parts are for repairs, the maintenance interval, and long-term reliability. And there’s safety: regulators and standards testing bodies (like UL and Consumer Reports) will want to see hard fall prevention and fault recovery before approving a stair-climbing robot for everyday use.

What it means for the consumer robot vacuum market

Household robots, led by vacuums and mops, already ship in the tens of millions annually, according to the International Federation of Robotics. But there are limits to how much they can automate cleaning due to mobility constraints. If Roborock can bring this feature to market with good performance, it pretty much lays out a whole new premium tier that rival Chinese, U.S., and European manufacturers are going to be forced to run after.

The company’s recent cadence, from detail-packed vacuum-mop combos to yard-care robots, indicates it has the engineering depth to productize ambitious concepts. That moment could be when household robots finally get vertical — and go upstairs.