The idea of a store sending a quadcopter after goods when they walk out unpaid is no longer sci‑fi. There are pitches from security vendors that promise aviator-speed drills in which autonomous drones would lift off from a roof, lock onto a suspected shoplifter, and stream live video to loss-prevention teams or police. One of these players, Flock Safety — famous for license plate cameras installed across the country in thousands of communities — has started selling a drone platform to private customers, suggesting it could complement guards and fixed CCTV with on‑demand aerial eyes.

The pitch is simple: faster response, more secure observation and better evidence with no dangerous foot or vehicle chases. The reality is more complicated, influenced by aviation protocols around the world and restrictions on battery life and precision — as well as privacy concerns and public acceptance of surveillance.

- What real-time pursuit could look like in retail

- The FAA rulebook is the largest gate for retail drones

- Privacy, bias and public trust around retail security drones

- Will drones really cut down on shrink in retail security?

- Signals from early deployments in public safety and retail

- What responsible adoption could be like for retailers

- The bottom line on retail drones for security and pursuit

What real-time pursuit could look like in retail

True “follow that suspect” capability depends on autonomy. Today’s commercial drones are already capable of taking off from sealed docks, avoiding obstacles and flying back to recharge without much human intervention. Throw in thermal sensors for low‑light tracking, computer vision to re‑identify a person across frames and license plate recognition to follow vehicles, and the tech roadmap all seems rather plausible.

But retail environments are messy. Busy parking lots, similar-looking clothing and occlusions all create edge cases where algorithms can drift. Any such system would have to include confidence thresholds, handoff logic between multiple drones and human‑in‑the‑loop oversight. Some of it is the management of evidence, too: authenticated video, clear audit trails and policies governing retention and access so that footage stands up in court but also doesn’t become a privacy hazard.

The FAA rulebook is the largest gate for retail drones

In the United States, most commercial flight is conducted under the FAA’s Part 107 rules — which typically call for a licensed pilot and line‑of‑sight control. Night operations and flights over people are permitted provided extra training and gear; routine beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) — the backbone of campus‑scale pursuit — still requires waivers or special permissions.

Police “drone as first responder” programs in cities like Chula Vista and Brookhaven have obtained custom approvals enabling them to send the aircraft when they receive a 911 call and stream it citywide. Retailers will not enjoy that flexibility on an automatic basis. Until the FAA completes its larger rules permitting broader BVLOS, any mall or big‑box chain looking to tail suspects beyond its property will experience regulatory friction and need airtight coordination with local law enforcement.

Privacy, bias and public trust around retail security drones

Despite clearing the aviation hurdles, there is rule‑based flight permission in its fragile social license. Civil liberties groups have raised alarms about the growth of automated surveillance, especially when private systems feed public law enforcement. San Francisco already prohibits certain types of face recognition, and cities from San Francisco to Portland have placed restrictions on it, including requirements for surveillance impact reports and council approval of new technologies.

Retailers have had hard lessons in misidentification. A federal lawsuit filed this week by the Federal Trade Commission against a national pharmacy chain for shoddy facial recognition practices — which included false accusations of theft — highlights just how high that bar must be when it comes to accuracy and accountability. Any drone program would have to include explicit restrictions: no biometric identification, minimal data retention, strong guardrails against tracking protected classes and independent audits for performance and fairness.

Will drones really cut down on shrink in retail security?

“Shrink,” a term for retail losses and damages, remains a headline problem. Shrink, loosely defined as the amount of inventory that goes missing between when a retailer logs the item into its book of accounts and when it sells at full price to customers (or writes it off), has hovered around an average of 1.6% on sales in recent years, according to the National Retail Federation’s annual Retail Security Survey, with tens of billions of dollars in losses per year. Within that, organized retail crime gets outsized attention in the field, though researchers say measurement is messy and sometimes exaggerated.

Pursuing individual shoplifters may not move the needle as much as stopping theft upstream. They could discourage after‑hours break‑ins, confirm alarms and give responders clearer understanding of what they were headed into — higher‑value use cases with fewer confrontational edge cases. A docked drone network can cover wide areas quickly, compared to deploying guards, but the cost is not trivial: after accounting for hardware, docks, data links, pilots (three are needed per shift at each site), maintenance, insurance and compliance — it adds up to tens of thousands of dollars a year per site. The case for ROI improves, however, when drones take the place of multiple routine patrols and cut down on false alarms — not when they’re cast as airborne bounty hunters.

Signals from early deployments in public safety and retail

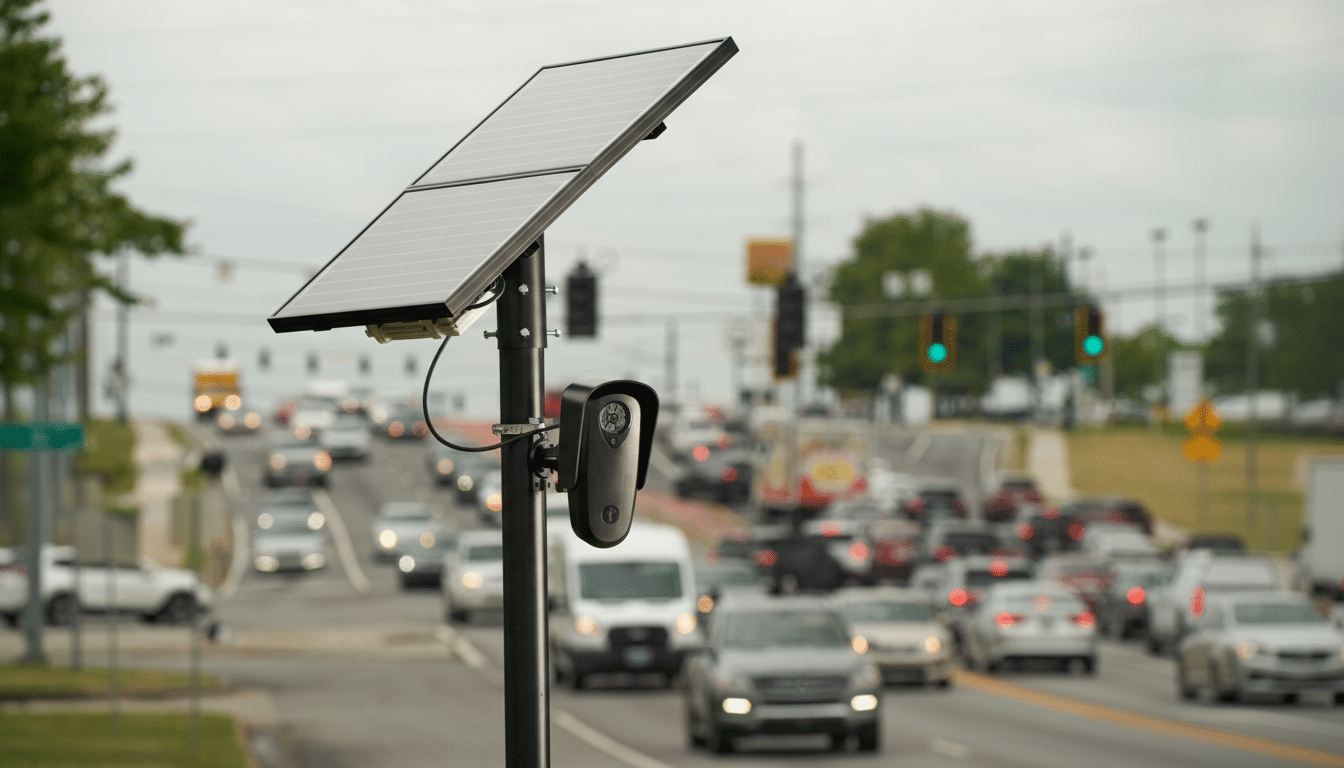

Public safety programs provide a glimpse of that. Police departments that fly drones say they’ve recorded quicker response times to crimes in progress and more cases solved without a high‑speed chase, sometimes getting to the scene of an incident before officers. Applying those ideas to private property will require tighter geofencing, clear handoffs to law enforcement off‑property and robust community engagement. Vendors like Skydio and DJI already sell “drone‑in‑a‑box” systems for perimeter security at campuses and warehouses — perhaps the first stop before retail parking lots.

What responsible adoption could be like for retailers

Good retail pilots would be local, limited and transparent: restrained hours, clear perimeters, signage at entrances; a narrow mission specific to verification of alarms or after‑hours perimeter monitoring, arriving only when called by the police. Off‑property trailing from the road should be banned except in cases where law enforcement takes charge. Policies should limit the duration of flights, constraining sensor zoom levels when they are close to public sidewalks and deleting (or averaging) non‑evidentiary footage soon afterward.

Success measurements would entail fewer false alarms, less risky confrontation and faster incident verification — along with reduction in measurable shrink impact within targeted categories. It’d be benchmarked against alternatives such as RFID, smarter shelving, exit analytics and staff training.

If those numbers don’t pencil, the spectacle of an intruding drone won’t outweigh the costs or controversy.

The bottom line on retail drones for security and pursuit

Could drones one day track shoplifters in real time? Well, actually, yes — and in small doses they already groom suspects for police. What’s plausible in the near term for retailers is also humbler: rapid response cameras that verify alarms and deter break‑ins, not pursuit aircraft buzzing down Main Street. “The tipping point is going to be a combination of clearer FAA BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) rules, proven accuracy, robust privacy guardrails and hard ROI,” he said. Until that happens, the smarter bet is to treat drones as mobile sensors that lower risk — and not as roving hunters of an airborne retail cat‑and‑mouse game.