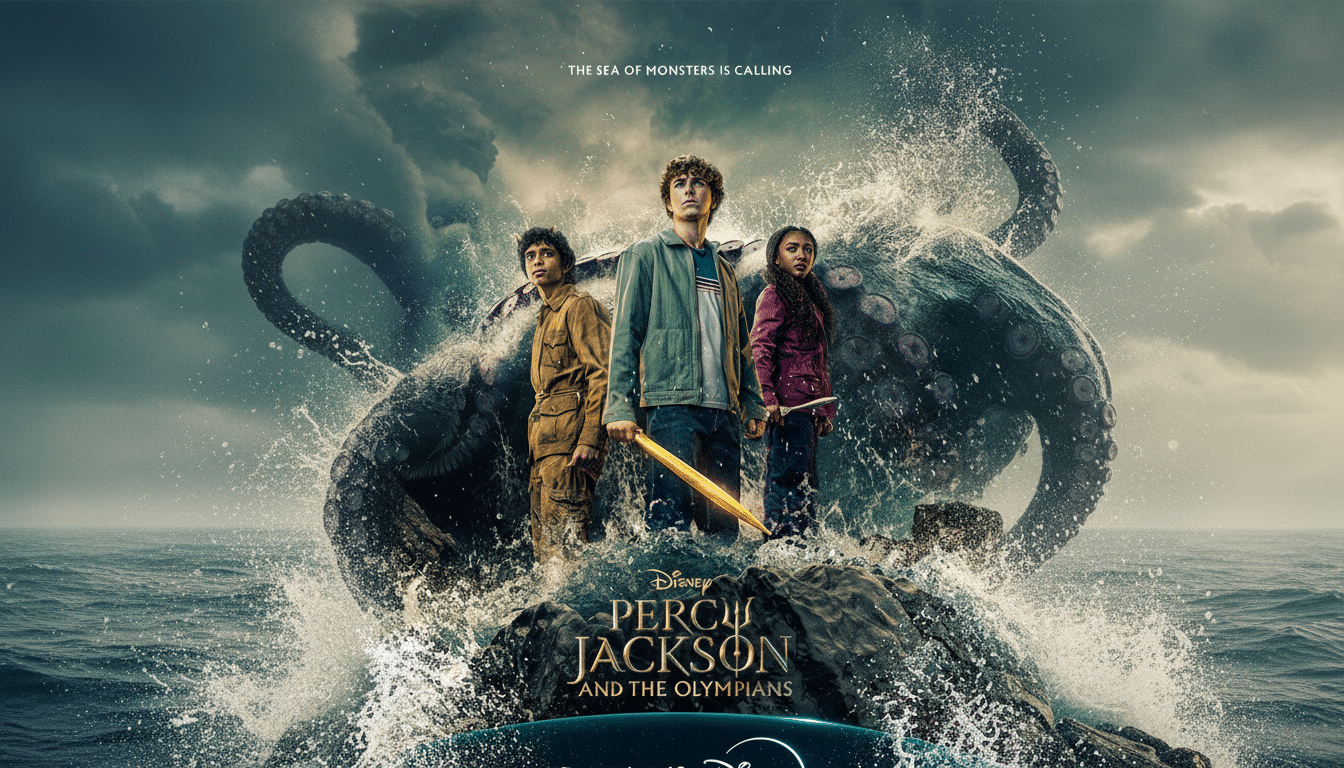

Percy Jackson and the Olympians revisits the map of The Sea of Monsters, and the series doesn’t wait long to recast the familiar terrain fans know from Rick Riordan’s 2006 novel.

Some are cosmetic, some structural and a few reframe character dynamics entirely. With Rick Riordan attached as an executive producer and co-writer, the alterations feel purposeful — targeted at serial storytelling and modern sensibilities — but they’re leading toward the same mythic endpoint all along. (The Percy Jackson books have sold more than 180 million copies worldwide, Disney Publishing Worldwide said, and so every departure lands under a microscope.)

Grover’s Peril and a Broader Rogue Demigod Web

The season still kicks off with Percy jolted by a nightmare involving Grover, but the geography and stakes get scrambled. And so, rather than poor Grover panting through a Florida bridal shop, the show leaves him in the jungle and cuts to a squadron of new demigods — Alison Simms, for instance — who have switched teams (to Luke’s and Kronos’s). That decision expands the map of threats beyond monsters, providing the season with a network of human antagonist forces that can intersect with the quest at multiple points. It’s a TV-friendly escalation, exchanging a one-off set piece for a revolving pressure system.

Tyson Reimagined at Home, Not Unhoused in Season 2

Tyson still comes to Percy as his Cyclops half-brother, but the journey is less rough. On the page, he’s unhoused and being protected by the Mist at Meriwether College Prep; on screen, Sally Jackson encounters him while doing volunteer work, takes him home with her and helps get him enrolled at Meriwether. The earlier reveal that Sally and Percy know his true nature ties them more powerfully together as a family and answers a niggling question for fans — how much does his mom really know?

It does other work, too, normalizing Tyson’s speech. In the book, Cyclopes age differently and Tyson speaks like he’s supposed to for a monster of his age; the show veers away from childish patterns here, following disability guidelines (and language advice generally) that discourage infantilizing language (such standards are often referenced by journalism groups such as the National Center on Disability and Journalism). The result is that his loyalty and exuberance remain intact without being caricatured.

The Dodgeball Ambush Moves and the Bulls Vanish

Riordan’s rousing opening — Laistrygonian giants disguised as “visitors from Detroit,” who at rocket speed transform a gym-class dodgeball game into a fireball barrage — is rerouted. The show sets the whole Laistrygonian attack on the way to Camp Half-Blood, effectively substituting out the Colchis Bulls’ initial assault of camp in the early part of the book.

What’s gained: urgency, without tacking on an entire school sequence and a consolidation of two large-scale VFX set pieces into one. (Industry reporting from outlets like Variety has reported that heavily effects-laden streaming episodes can cost in the eight figures each, so cuts like this are standard practice.) What’s gone: the droll ordinary-meets-mythological fang (name tags like Joe Bob, Skull Eater, Marrow Sucker) that rendered the original dodgeball scene another quintessential Percy joke regarding gods cut into everyday life.

Chiron’s Firing and the Poisoned Tree Timeline

In the book, Chiron’s parentage by Kronos gets him dismissed from Camp Half-Blood and lands him as a lead suspect in Thalia’s tree poisoning. The series trims the whodunit. Chiron is thrown out simply because of his parentage, and Luke’s foretaste of poisoning the tree is shown on-screen. The adaptation front-loads Luke’s villainy, and jettisons the “Is Chiron compromised?” mystery beat, then, making it more of a defined hero–antagonist line for the season rather than a camp-side procedural.

Annabeth — The Prophecy and a Sharper Quest: Politics

The show gives Annabeth more early narrative weight by having Chiron reveal the Great Prophecy to her and tell her not to send Percy on quests. That decision sets off a bunch of fraught beats — discussions of how to sabotage the chariot race, a push to send Clarisse on the Golden Fleece quest without Percy — that aren’t in the book. The friction recasts “Percabeth” from playful competition into a question of personal ethics, a teen-drama texture that the serial TV form can mine over multiple episodes.

It also makes Clarisse’s demand for the quest feel less like a plot technicality and more like camp politics: who deserves titles, wielding danger, and how leadership works when gods are taking notes. It fits thematically with the series’ overall emphasis on agency versus destiny.

What Stays the Same and Other Notable Points

The backbone remains: Percy, Annabeth and Tyson set off for the Sea of Monsters to seek out the Golden Fleece; Clarisse continues to lead.

But dropping in rogue demigod shit-stirrers also gives Luke a season-long contraption, illustrating how Kronos’s influence eats at not only gods but kids warring over the battlefield. Exposing Luke’s betrayal early leaves Percy even more vulnerable, just as Tyson’s reorientation empowers the series with one of its most powerful underlying themes: found family is not a consolation prize; it is a superpower.

If for the first season the books’ heart was not lost in translation, this second season makes clear that the writers are happy to rearrange some of the furniture to accommodate television’s weekly rhythms. The result now is a bolder, cleaner conflict map that still respects the quest fans fell for — if with some monsters moved over and motivations cranked up.

Percy Jackson and the Olympians is streaming weekly on Disney+, with additional installments set to put these new dynamics to the test against sirens, sorcery, and storms in store in The Sea of Monsters.