Astronomers have identified an unusual gamma-ray burst that hung around for hours and flared up a number of times after the initial explosion, so odd that it could be in a class of its own as something never seen before.

Called GRB 250702B, the outburst shattered duration records and behaved in ways that standard models are hard-pressed to explain, leading to the hint that black holes may be able to shred stars in new ways beyond what textbooks now describe.

A Burst That Would Not End, Blazing for Hours on End

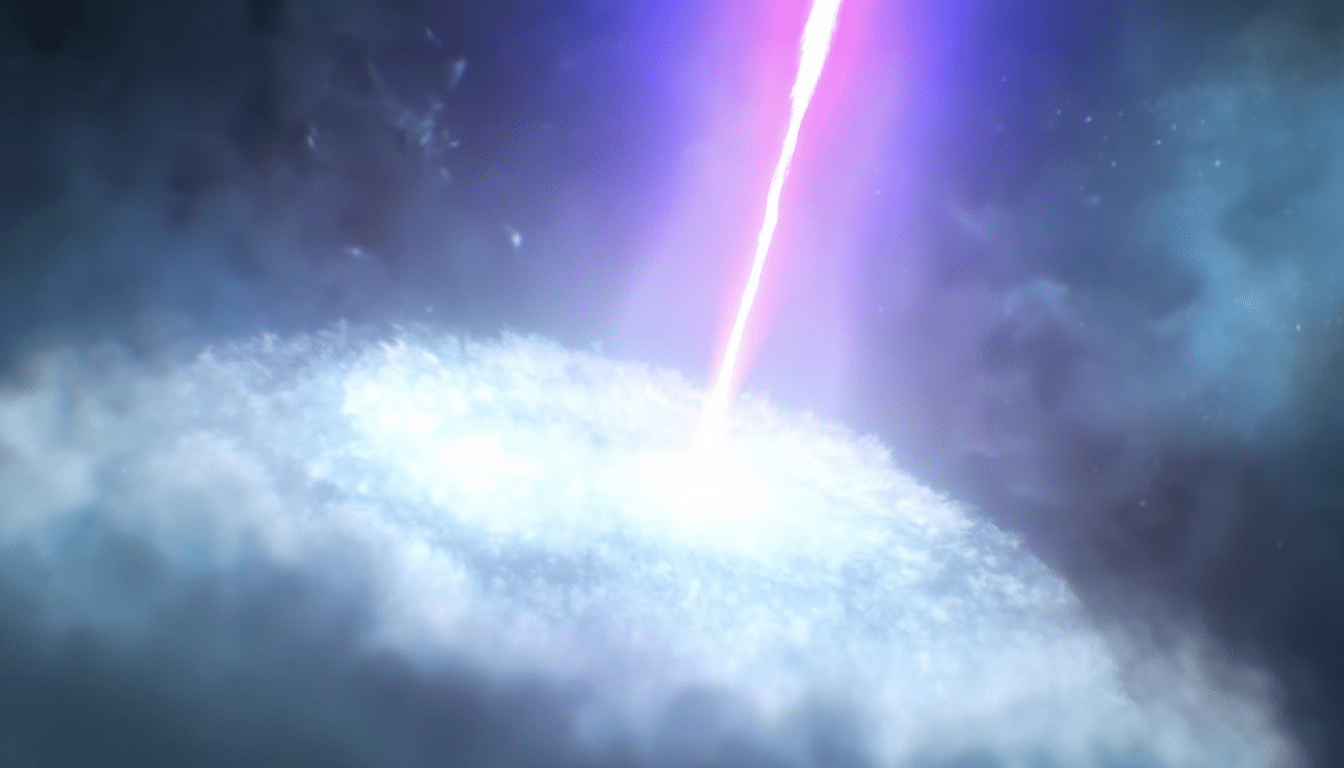

Gamma-ray bursts are the most powerful explosions in the universe, typically produced by either a collapsing massive star or colliding neutron stars. They tend to burn for seconds to minutes. GRB 250702B stuck around far longer: its first blast of high-energy light persisted for at least seven hours, and the afterglow continued to explode in X-rays for days. In an age in which most bursts dim before observatories can point a telescope, this one left the lights on.

The flash was spotted by a network of space observatories, which included NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory. Since no single instrument could observe the entire episode, teams patched together a continuous timeline using several satellites and subsequently followed up the host environment with imaging from the James Webb Space Telescope and Hubble Space Telescope.

Analysis puts the source in a galaxy approximately 8 billion light-years from Earth. Data from Webb and Hubble reveal the outburst piercing through a major dust lane, hinting at a complicated, potentially merging system. The amount of energy involved was astronomical — equivalent to 1,000 Suns shining for 10 billion years — and it streamed far more powerfully than scientists ever imagined: in narrow, relativistic jets that just so happened to be pointed at Earth.

Why It Breaks the Rulebook on Gamma-Ray Burst Behavior

Studies of GRBs tend to split events into “short” vs “long,” where long are those with durations greater than a few seconds, and isolated from their parent supernova (SN). A small population of ultra-long GRBs extends to several thousand seconds. GRB 250702B tops even that: the hours‑long gamma rays, delayed and prolonged X‑ray afterglow and absent obvious supernova signature are nothing like any pattern ever observed in decades of watching.

One particularly “interesting” twist: X-rays began to brighten about a day before the main gamma-ray fireworks, rather than afterward, as is typical. That timing together with the bizarre duration could indicate that the system’s power plant flicked on and off in stages, or our view penetrated thick variable dust that modulated the emerging radiation.

For context, the “BOAT” event of 2022 — the brightest flare ever recorded — was record-setting in terms of strength and not duration. GRB 250702B flips the script, instead pushing the duration limit. Of the 1,600+ triumphs recorded by Swift and thousands more detected by Fermi’s instruments, durations of over one hour are very rare indeed, unlikely to be much greater than a fraction of the 1% total sample.

What Could Power It: Candidate Black Hole Scenarios

The leading explanations center around black holes simply doing something strange to a star next door. One possibility is that an intermediate‑mass black hole, thousands of times the mass of the Sun, has shredded a star that ventured too closely. Hot accretion disks form, deflecting spiraling debris out and into jet-launching paths close to the speed of light that produce prolonged gamma rays. Intermediate‑mass black holes are notoriously difficult to detect, so a pulse like this could serve as an invaluable business card.

Alternatively, it is a low-mass stellar‑mass black hole in a binary configuration. Having siphoned gas from its companion across a long lead-in, it might plunge into the envelope of the star and quickly devour it, fueling a jet for tens of hours. In both cases, “fallback accretion” delivers continuously long-lasting power in which a stream of material torn from the star feeds the central engine.

Not supported by the data is a garden‑variety collapsar with a bright supernova. No obvious supernova signature has been reported, despite sensitive follow‑ups, which leans toward disruption or swallowing rather than a classical massive‑star demise.

How Scientists Put It Together With Global Observatories

Teams of scientists at NASA, other U.S. institutions and in Europe collaborated on rapid-response, multi-frequency observations, enabling links between the timing of gamma-ray events from Fermi and Swift with X-ray, optical and infrared images. Where the exceptional resolution of Webb came into play was in mapping the dust structures within (and surrounding) the host galaxy—Hubble provided supplementary imaging, to determine exactly where it calls home. These early results are being submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, with accompanying analyses published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The synthesis indicates that the burst had a dusty, ever-changing host; always-on jets pointed near our line of sight; and a central engine that remained active well past what standard models predict. Together, these clues add up to the possibility of a new or rare channel for making GRBs—one that the next generation of telescopes will now be poised to discover.

What Comes Next for Studying Ultra-Long Gamma-Ray Bursts

To determine if GRB 250702B kicks off a new class, astronomers need more examples. Wide‑field surveys, of course, will be key, as will rapid follow-up at facilities for high‑resolution imaging and spectroscopic studies. Missions like Fermi and Swift are still at the heart of them, though new platforms, along with coordinated ground-based networks, should be able to catch more ultra‑long bursts in the act.

If the intermediate‑mass black hole scenario is correct, GRB 250702B may provide a clue to the long‑standing mystery of how black holes grow from stellar remnants to become supermassive objects. If engulfed‑companion scenarios are the final outcome, it will stretch our comprehension of how binary stars evolve during their last catastrophic moments. Either way, an outpouring that has lasted longer than any on record has pried open a new window on how the universe rips stars to shreds — and how those mayhem pluckings illuminate the cosmos.