A fast-moving Android malware campaign is seeking to extort money from smartphone users by essentially taking over their phones, then locking them out until they pay up — and the security researchers who have studied the scheme warn that criminals could easily use those methods to secretly take over bank accounts in which victims have stored any app-based biometric authentication information or keys wherever transaction processing systems handle mobile payments.

The research into this pretty ugly attack comes courtesy of experts at fraud-intelligence firm Cleafy.

- How the Albiriox Android banking attack scheme works

- What makes the Albiriox strain different from other threats

- Who is most at risk from this Android banking malware

- Red flags that may indicate your Android device is compromised

- Practical steps to reduce your risk and protect your money

- What banks and Google can do right now to fight these attacks

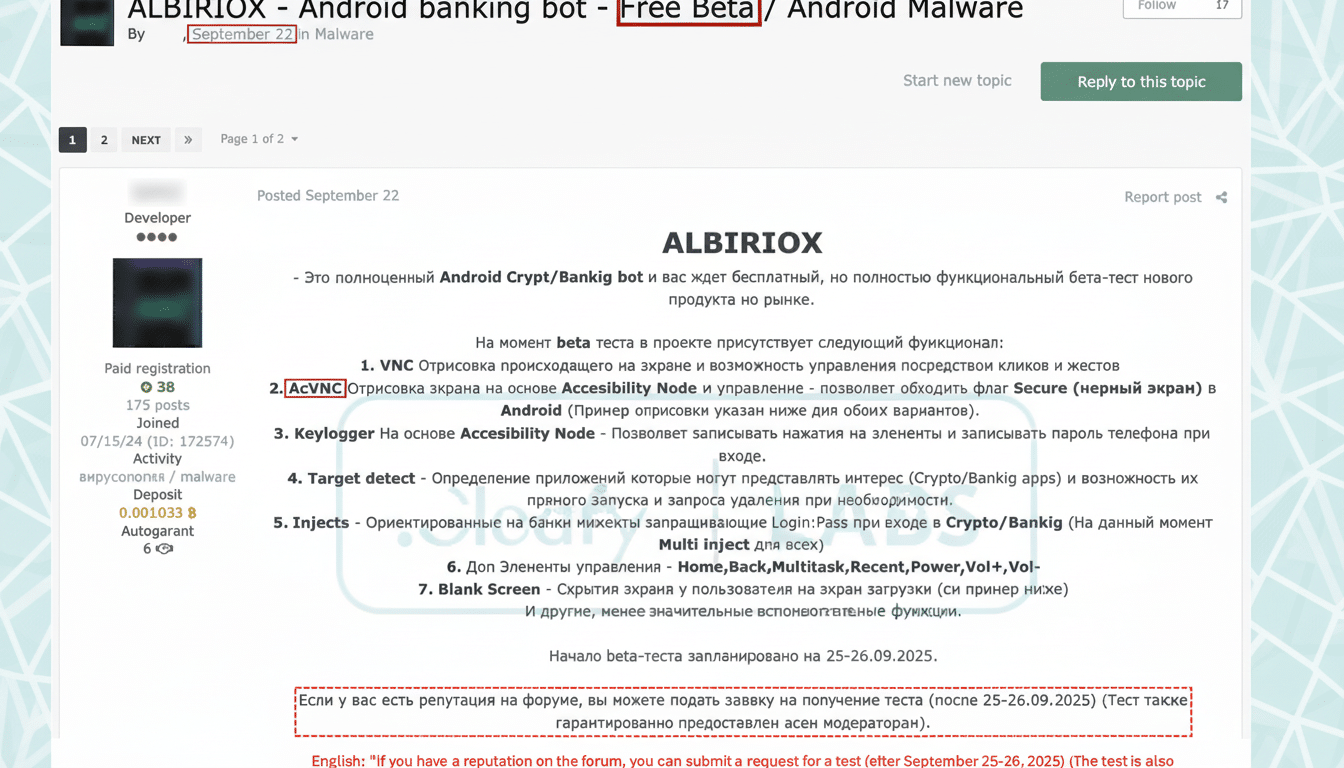

The strain, known as Albiriox and publicized by independent reporting from Android Authority, combines convincing fake app pages with more robust remote-control power that allows attackers to monkey around in banking apps as if they had the device in hand.

How the Albiriox Android banking attack scheme works

The lure begins off-platform. Targets are guided to outside sites which are nearly identical clones of real Google Play listings for popular financial apps. The pages contain genuine logos, real-looking screenshots and a recognisable “Install” button – although herein lies the trick; in pressing on it, users are either directed to an official store link or an infected APK file.

From that point on, the malware relies on social engineering to allow “install unknown apps.” Settings screens have trained users to be nudged into granting permissions, often by way of “updating” or “unlocking” features. After it is installed, Albiriox allegedly requests high-impact privileges — notably Accessibility Services — to read what’s on-screen and mimic taps, swipes and text.

Once they have those rights, the attackers can remotely open a banking app, go to transfers, input amounts and approve transactions. The activity comes from the victim’s own device, so normal defences that watch for strange logins from new locations or browsers become less useful. And researchers say the malware has the capability to intercept notifications or SMS messages in order to capture one-time codes, bypassing many forms of multi-factor authentication.

What makes the Albiriox strain different from other threats

Typical banking malware includes a theft step followed by an attempt to log in from some machine of the attacker, which by itself would trigger fraud models. Albiriox flips that script: It stages on-device fraud. This approach piggybacks on the device fingerprint, app session and IP reputation of a legitimate phone to send transfers that appear as normal for automated risk engines.

That combination of credible fake app pages, stealthy permission harvesting and real-time remote control obviates the need for password theft entirely. It’s a playbook we’ve observed in mobile banking trojans of late, yet Cleafy reports that Albiriox feels polished, fast and purpose-built for taking the money as soon as it appears before banks or victims can do anything.

Who is most at risk from this Android banking malware

Anyone who sideloads apps is a target, especially users who install “updates” or “new features” from links in texts, emails, search ads or messaging threads. Previous big Android banking trojans have started with European financials before widening to North America and APAC; Cleafy monitoring usually begins in the EU where attackers find success and bunch there.

The attack surface is large. Android dominates about 70 percent of the world’s smartphone market, StatCounter estimates, and even a tiny bit of success at that scale can mean big losses. Data compiled from law-enforcement reports, call-center trends and annual surveys conducted by the F.B.I.’s Internet Crime Complaint Center show that online fraud has cost billions in consumer losses, despite being mostly preventable; account-takeover crimes are especially damaging.

Red flags that may indicate your Android device is compromised

- Fake Play pages that are hosted on non-Google domains or opened from direct links, rather than found through the Play Store app itself.

- Surprise prompts for “install unknown apps,” Accessibility Services, or perhaps device admin (unless an app has been updated to prompt users and it shouldn’t — anything newer than April must ask your permission).

- Phantom taps, sprinting battery drain, spontaneous overlays or an inability to back out of screens — is your phone haunted, or being controlled from afar?

Practical steps to reduce your risk and protect your money

- Download financial apps by opening Google Play and searching with the related bank’s name as your keyword.

- Never click “Install” buttons on a web page, in an email, or on an ad.

- Disable “install unknown apps” for all browsers and messaging apps. If you turned it on earlier, switch it off in Settings.

- Check Accessibility permissions and revoke them for any app that isn’t a screen reader or a widely known utility from a reputable developer.

- Activate Google Play Protect and tell it to scan apps that are “installed from unknown sources.” Make sure Android and all applications are up to date.

- Use banking alerts on every transaction, set low transfer limits and enable app- or hardware-key-based MFA where available.

- If your phone is acting up inside a banking app, pause and call your bank using a trusted number.

- If you fear infection, disconnect from networks until you back up and factory reset. Then reset banking passwords, end app sessions and re-enrol MFA on a clean device.

What banks and Google can do right now to fight these attacks

On the platform side, increasing Play Protect’s real-time scanning of sideloaded packages as well as identifying deceptive “fake Play” websites can help blunt the first step in these campaigns. Banks will be able to supplement device-binding, behavioral biometrics and specially tuned session analytics checking for automated taps and impossible navigation patterns, as well as dynamic step-up checks where Accessibility is on.

For Cleafy, the research points to a larger trend: Mobile fraudsters are conducting transactions from the victim’s own device. Staying ahead of that tactic will require coordinated actions by both Google and app developers, as well as banks — and vigilance by users who should view any sideloaded financial app as a red flag.