Neuralink says more than 10,000 people have so far expressed interest in one day receiving its N1 brain implant, highlighting strong demand for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) despite the fact that it remains largely trapped within clinical trials. The company president and co-founder DJ Seo provided the figure in a briefing, quoted in a Morgan Stanley client report, characterizing the backlog as both validation and an enormous operational headache.

Soaring Demand Collides With Limited Eligibility

For now, the line is mostly aspirational. Neuralink has already implanted the N1 in 12 trial participants and hopes to have approximately two dozen people with implants by year’s end, Seo said. The trial is open only to those who suffer from severe upper-limb paralysis due to spinal cord injury or ALS, so the list of 10,000 far surpasses today’s medically eligible population and the company’s current capacity.

The interest is a reflection of the potential hands-free computing holds for those who are not reliably able to use a keyboard or mouse. According to early users, people use it for about 7.5 hours a day on average (with one user clocking over 100 hours in a week) — a pattern of usage that looks much less like checking in with a medical device and more like what you do with your smartphone. It hints that the system is stepping over a key threshold: from an occasional assistive tool to a relentless interface.

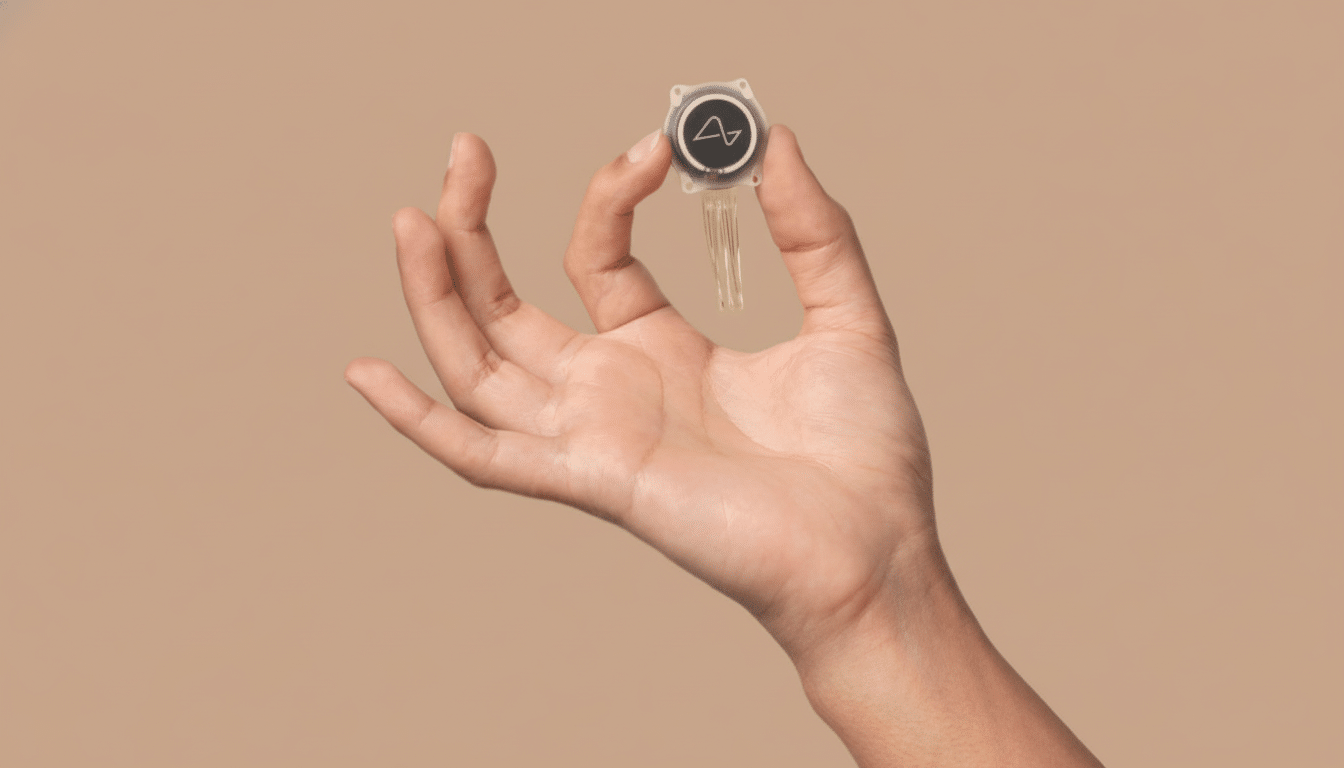

Inside Neuralink’s N1 and Telepathy Platform

Neuralink’s N1 is an entirely implanted device that records neural activity using flexible threads tipped by electrodes. The company’s Telepathy software interprets those signals — intended movements and, in preliminary research, fragments related to speech — and wirelessly sends commands to a connected computer. The end-to-end latency of the system can be penetratingly faster, by an order of magnitude, than your brain talking to your muscles — a benchmark that is fairly seductive in many applications where you’d like a computer to be involved in high-speed interactions with human users (for gaming or just rapid text entry).

The first two public participants have demonstrated what that looks like in practice by using the implant to type, browse, bank and play games. A filmed demonstration of cursor-based chess demonstrates a phenomenon found in other academic BCI experiments: once the interface feels intuitive, people use it for ordinary life instead of just lab tasks.

Robotic Surgery Is Neuralink’s Central Scaling Bet

Seo stressed the surgical robot as Neuralink’s core differentiator. The tool has made it possible to automatically insert ultrafine electrode threads with micrometric resolution — something that is complicated, time-consuming and tiring for human hands. Neuralink designed the robot to circumvent a structural bottleneck: There are only a few thousand practicing neurosurgeons in the United States, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, and practically none have been trained for these new BCI procedures.

Still, the procedure is not surgeon-free. Craniotomy is still performed, the implant still inserted, the robot’s actions are supervised by clinicians and intraoperative safety decisions are made. Industry peers echo this nuance. Executives at INBRAIN Neuroelectronics and other neurotech companies point out that automation markedly enhances precision and repeatability, but the responsibility for patient safety ultimately lies with human surgical teams.

Neuralink’s method stands in contrast to Synchron’s stent-like implant, which is threaded through the vasculature without the need to open the skull. That minimally invasive approach may scale differently — more like an interventional radiology workflow than neurosurgery — which serves to illustrate how the BCI field is dividing along hardware and delivery lines, all with a focus on one outcome: enduring, reliable neural data.

Clinical Reality Check And Regulatory Path

With a buzzworthy waitlist, this is still experimental medicine. No BCI, including Neuralink’s, has been approved for commercial sale by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States. Neuralink is operating under what are known as investigational device exemptions, and so are academic programs (including the long-term BrainGate program) and private companies like Synchron. During a recent brain–computer interface forum presented by Mount Sinai Neurosurgery, Michael Lawton of the Barrow Neurological Institute said he had performed several procedures using Neuralink but added that risks associated with open-brain surgery preclude elective use in healthy people.

Timelines are unclear, but some industry leaders like Tom Oxley, the man behind Synchron, are saying initial market approvals could be seen in a couple of years if safety and durability data hold. Important early markers include the maintenance of stable signal quality over months to years, absence of surgical complications in a carrier-dependent manner (to induce a sustainable response), reliable wireless performance and unequivocal functional gains that are relevant for patients and payers.

What a 10K waitlist signals for brain–computer interfaces

The sheer scale of Neuralink’s waiting list speaks to a larger sea change: Assistive neurotechnology is shifting from the domain of research whimsy to one that patients actively pursue. For regulators, that means pressure to judge BCIs not only by lab metrics but also day-to-day outcomes like how fast someone can communicate, how well they maintain digital independence, and their quality of life. For hospitals and insurers, it presages a host of questions about training, reimbursement and the long-term maintenance of implanted systems.

For Neuralink, turning curiosity into an opening in your skull will come down to manufacturing, surgical bandwidth and long-term safety. The robot may serve as the lever that allows scale, but clinical prudence will determine the pace. If early data keep showing heavy daily usage and meaningful gains for people who are unable to move, that 10,000-person line will be less a marketing slogan than an early indicator of pent-up clinical demand — one that the entire BCI ecosystem will have to help address.