Neon, a popular viral app used for recording phone calls, has silently been taken down in light of reports that it let its two million users listen to recordings and read transcripts made by other users while testing the app. The closure comes after TechCrunch, which confirmed the exposure by examining network traffic using a security tool, Burp Suite, reported on it.

In a statement, Neon’s founder, Alex Kiam, informed users that the service will be temporarily unavailable as “extra layers” of protection are built in. The initial investigation indicated that both Apple and Google were informed about the problem. The episode immediately transformed a quickly growing growth hack into a cautionary tale about what happens when data-hungry business models meet some very basic security holes.

What Triggered the Takedown of the Neon App

Reporters found that call transcripts and audio could be accessed through publicly available links, allowing anyone with the URL to listen in — worse yet, Neon’s back-end system could even be coaxed into returning information on other users’ recent calls, hinting at weak access controls for such sensitive data.

This wasn’t a clever zero-day; it was the sort of permission error security teams find during standard code reviews.

The exposure TechCrunch discovered wasn’t just limited to test accounts. In concrete terms, the flaw risked turning private phone calls into downloadable files — that’s a nightmare for an app that also doubles as a service for personal, professional, and potentially regulated communications.

How the Exposure Happened Inside Neon’s Systems

Although Neon has not released a complete postmortem, the indicated behavior matches common failure modes that I see: unauthenticated or low-authenticated endpoints, publicly reachable object storage, and predictable resource identifiers. Broken access control has a high-profile position in the OWASP Top 10 because, when news breaks about a particularly damaging data leak or breach of trust victimizing end users, it usually comes down to some tiny oversight in an API that was never supposed to be public.

Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report has long reported that misconfigurations, and the human factor at large, are responsible for a significant portion of breaches — particularly in cloud-first stacks. At a time when the “product” is intimate audio and text, even a tiny oversight can have disastrous consequences.

A Business Model Based On Data And Consent

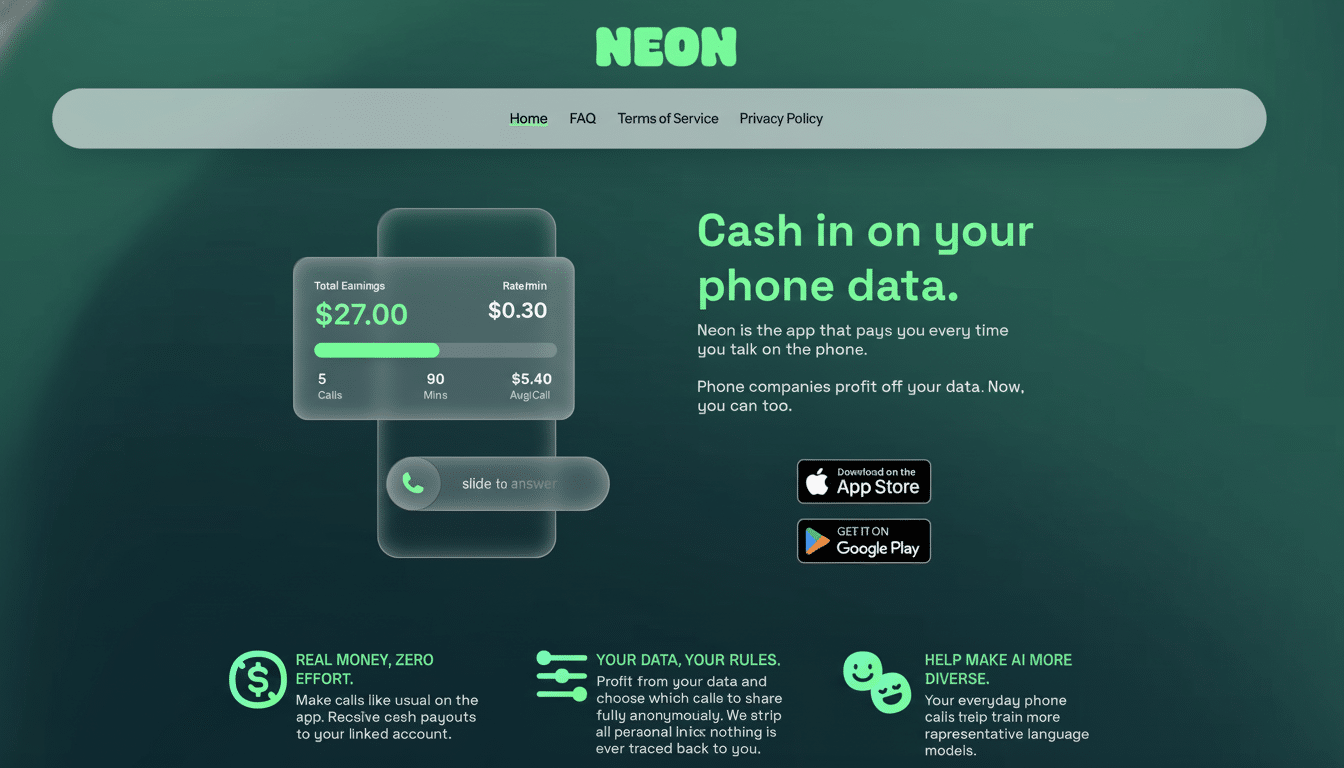

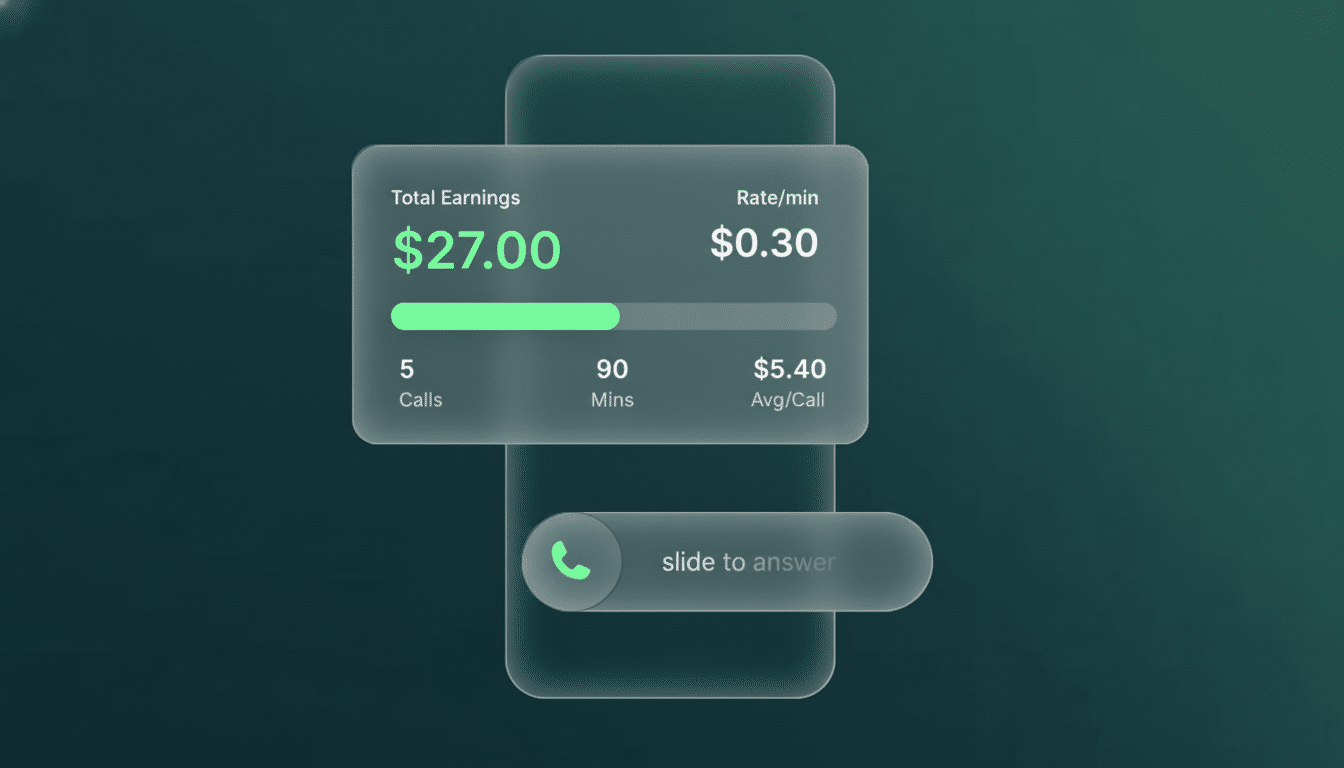

Neon’s pitch was audacious: Record calls made through the app, scrub them of any personal information and then sell the resulting data to artificial intelligence companies that were using people’s conversations for training their digital assistants. For their participation, users were paid up to $0.30 per minute. The company argued that the data was de-identified, but privacy researchers have long said conversational data is extremely difficult to anonymize; unique phrases, voices, and context can be pieced together to re-identify speakers.

The law can also be complicated. Twelve U.S. states have all-party consent laws with respect to recording calls, and generally regulators disapprove of opaque data monetization. Even where single-party consent is in force, the Electronic Frontier Foundation warns that if you record secretly or without clear notification, you might still run afoul of wiretapping laws or employer policies — and platform terms like those from Facebook and Snap prohibit secret recordings too.

Platform rules add another layer. Google cracked down further on call-recording apps that use Android’s Accessibility API in 2022, and both app stores demand clear notification and good security for apps that have access to sensitive information. Neon’s exposure — plus reports of some people who were apparently trying to “game” payments by recording ambient conversations of those around them — also illustrates how quickly consent can falter in practice.

Regulatory and Platform Pressure on Call-Recording Apps

Instances like this also draw attention beyond app-store compliance. EU and U.S. privacy regulators have increasingly eyed data brokers and AI training pipelines. The GDPR says of processing voice data for AI that you need a clear legal basis, purpose limitation, and minimization of data — hurdles hard to clear when security controls leak like a sieve. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission has taken enforcement actions against companies that failed to properly secure sensitive information or misrepresented their privacy practices.

The industry has played out these echoes before. In 2021, Clubhouse drew criticism for an unofficial client re-broadcasting audio rooms, highlighting that platform design choices can lead to privacy risks even in the absence of a classic “breach.” On Neon, the problem of monetization and exposed endpoints is even worse: it mixes a consent failure with a direct security one.

Why It Matters for AI Training Data and Compliance

Tightly held AI labs at companies fight for high-quality conversational datasets. But where training corpora contain recordings collected without robust consent or other appropriate protections, developers inherit legal and ethical risks. Recent public debates — from meeting platforms changing their terms around AI to lawsuits about the origin of datasets — indicate that the market is shifting toward traceable, rights-cleared inputs. Apps that can’t document that chain of custody will have fewer buyers for their data and more inquiries from regulators.

What Users Can Do Now to Protect Their Call Data

Neon users, current and past, may want to delete the app, revoke microphone and call permissions the app requested from your device’s settings panel, and request that their data be deleted from Neon’s servers. If calls with non-users were saved, it may be worth telling them as well, particularly in all-party-consent states. Businesses can add to mobile app allowlists and MDM policies that block unvetted call-recording apps funneling sensitive audio to third parties.

The broader lesson is plain: Products based on intimate data cannot move fast and break things. Security-by-design, sound access controls, and demonstrable consent aren’t add-on features — they are the business model.