NASA is opening competition for a crewed lunar lander that will carry astronauts to the Moon under Artemis, and the move amounts to a strategic reset that places SpaceX’s Starship on notice of its intentions and invites Blue Origin, and potentially others as well, into the mix. The decision comes after pointed public comments from NASA’s acting administrator that SpaceX is running behind schedule — and a scathing retort by Elon Musk on X, in which he taunted competitors and defended Starship’s timeline.

Why NASA Is Reopening Its Lunar Lander Contract Deal

The agency’s aim is simple: to minimize schedule risk for a timely, repeatable return to the lunar surface. The current Human Landing System plan is betting on SpaceX’s Starship HLS to stack firsts — extended orbital operations, multiple cryogenic propellant transfers in space, astronauts landing precisely on the Moon in orbit and with legs. Complex serial dependencies, such as these multiple launches served by a single spacecraft and other examples mentioned earlier in this paper, have been identified by NASA’s safety advisers and independent auditors as schedule threats that date back some time. It’s playing a classic NASA card of competition, hedging technical risk with a quest for speed, and sharpening pricing through milestone-linked payments.

NASA also faces geopolitical pressure. Leaders of the agency have pitched the Moon campaign as a test of American technological leadership at a time when programs are moving forward overseas faster than ever. To that end, two development tracks — two landers, two supply chains, and two teams solving hard problems — provide redundancy if one design falters. The Government Accountability Office has repeatedly discovered that dual-track procurement can help ensure better outcomes for high-risk projects when milestones are strictly enforced.

Where SpaceX Stands on Starship and HLS for Artemis

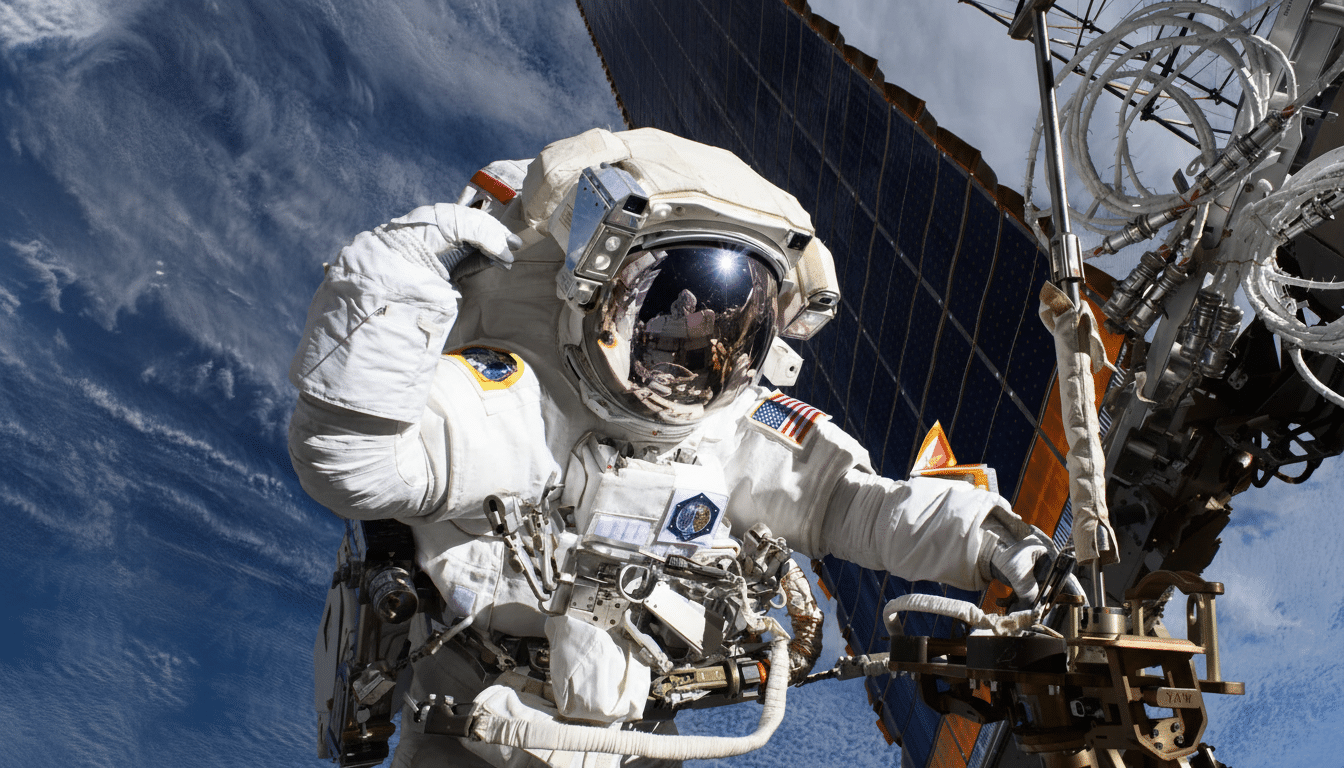

SpaceX was awarded the HLS contract, and subsequently some additional uprated contract value as the mission grew in scope. The agency has spent about $2.7 billion to date, according to the budget documents and program briefings. In that time, Starship has gone from early flight tests to demonstrations that concluded with both stages returning all the way to splashdowns — a significant step toward recovering and reflying in a controlled fashion.

But the most difficult work is still to come. And for the Artemis landing architecture SpaceX has put forward, it would have to demonstrate that capability at scale — perhaps across multiple tanker flights — before deciding to send a fully fueled HLS to lunar orbit. For that string, the launch cadence needs to be high, and ground infrastructure needs to be mature and highly reliable in space operations. Despite SpaceX’s remarkable achievements to date, from a record-breaking 11 Falcon 9 missions in the first three months of this year alone to its successful human spaceflight launch and recovery of Crew Dragon, the development curve for Starship is significantly steeper with several mission-critical elements (e.g., thermal protection system) unretired.

Blue Origin’s Opening, And The Alternatives

Blue Origin already has a multibillion-dollar contract for another lunar lander that was designed to fly later in the Artemis sequence. That vehicle, Blue Moon Mark 2, also depends on in-space refueling and would launch on top of New Glenn. The company has recently rounded a significant programmatic milestone as its New Glenn flew to orbit on first flight, an inflection point for Blue’s heavy lift dreams and prerequisite first step toward any crew-capable lunar stack.

Industry reporting has noted a “Plan B” being considered over at Blue Origin: to fast-track the development of a crewed version of its smaller “Blue Moon Mark 1” lander — which, like Starship, is engineered not to require in-orbit refueling for its mission profile. For NASA, where a quicker/less dependent demonstration is a significant focus, the simplified lander architecture might have some appeal — if served with an available launch system and meaningful testable flight plan.

Legacy aerospace is circling, too. And firms like Lockheed Martin have already indicated that they are prepared to bid crewed landers that utilize Orion-era systems engineering, extensive experience in human-rated flight hardware and established supply chains. That strategy could give that program the necessary stability, although beginning with a clean-sheet crewed lander would have its schedule and cost challenges without aggressive downselects and milestone gates.

Musk’s Reaction And The Politics In Play

Musk ridiculed NASA’s change as unnecessary and questioned Blue Origin’s capabilities, saying that Starship would ultimately do the entire Moon mission. His posts crystallize a larger argument over procurement strategy: should NASA put more of its resources into the most mature path, or hedge by splitting its bets to spread out the catastrophic risk if one architecture face-plants? The administration’s emphasis on speed — and political jockeying, as well as oversight dynamics, that are developing — adds a political layer neither contractors nor engineers can afford to ignore.

One thread is that of agency head and governance. Coverage in leading media has indicated internal talk about permanent-leadership appointments — and even department realignments — with implications for civil space across the board. Continuity is important for a human lunar landing — stable lines of authority, predictable budgets and clear technical baselines are what distinguish pie-in-the-sky milestones from repeatable missions.

What To Watch Next in NASA’s lunar lander competition

Crucial signals will come from the new request for proposals: how NASA apportions milestone payments, how much it values actual flight performance over paper designs, whether it insists on orbital refueling demos before investing in a crewed timeline. Watch for SpaceX to pick up the pace on tanker and prop transfer tests, for Blue Origin to ramp up New Glenn flight rates and Blue Moon hardware testing milestones, and for someone new to demonstrate bona fide hardware (not just concept artwork).

NASA’s independent watchdogs — the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, the Office of Inspector General and outside review boards — will scrutinize risk tradeoffs and schedule realism. The quickest route to a return to the Moon might not be a straight line; it could well be a race of sorts between two capable landers, each one flying key technologies that now only exist on paper. If the reopened competition results in that redundancy, then NASA has some choices. And when it comes to lunar exploration, choices are the difference between planting one flag and a sustainable return.