NASA’s next crewed expedition beyond low Earth orbit is locked to a tightly choreographed, 10-day timeline that reads like an astronaut’s field manual. Artemis 2 will send Orion and its four-person crew—Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen—on a sweeping loop around the moon and back, validating the spacecraft and operations that will underpin future lunar landings.

The mission is a readiness test: life support, navigation, communications, and human-in-the-loop piloting all get trial runs in deep space. If the trajectory holds, the crewed Orion—call sign Integrity—could surpass the human distance mark set during Apollo 13, skimming thousands of miles past the lunar far side on a free-return path home.

- Launch and initial Earth orbit checkout procedures

- Nighttime orbital burn and life support system trials

- Translunar injection burn and resilient free-return path

- Far side lunar pass and potential distance record

- Coast home, atmospheric reentry, splashdown and recovery

- Why this timeline matters for Artemis lunar ambitions

Launch and initial Earth orbit checkout procedures

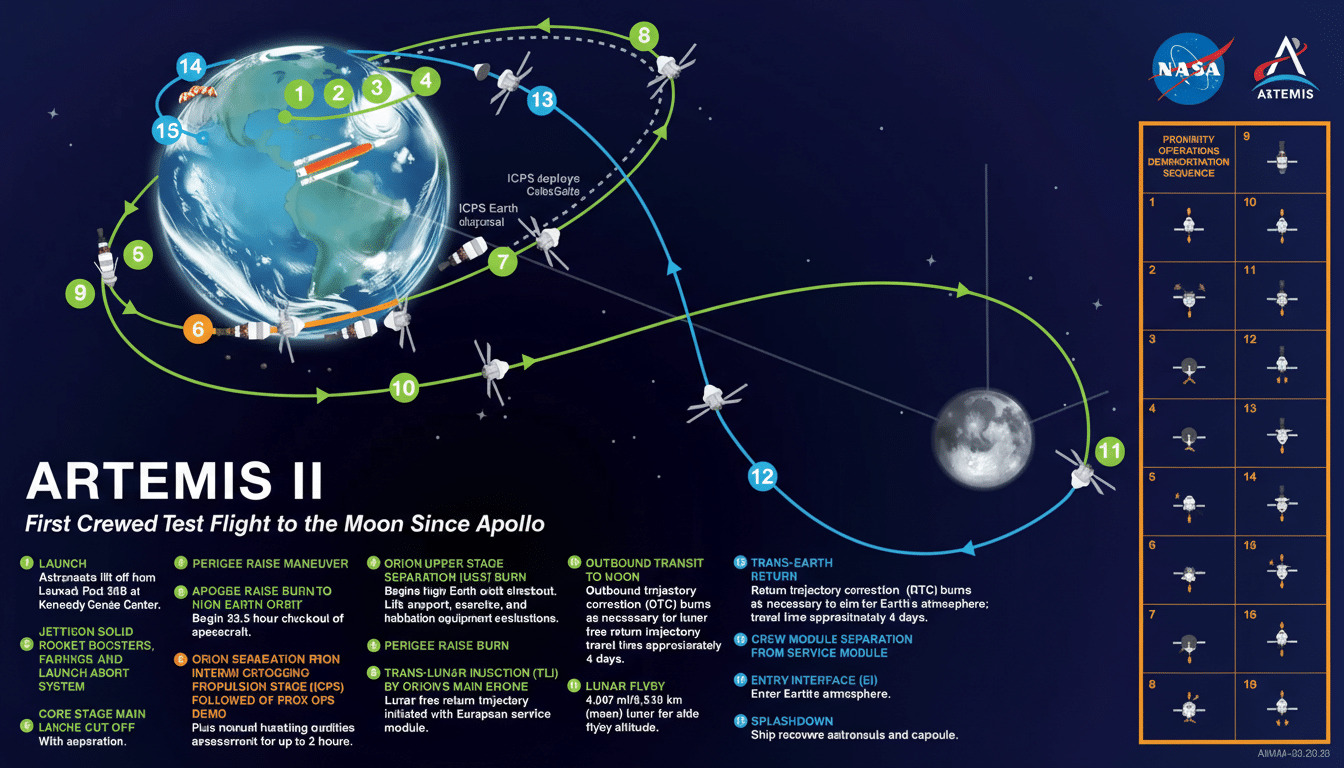

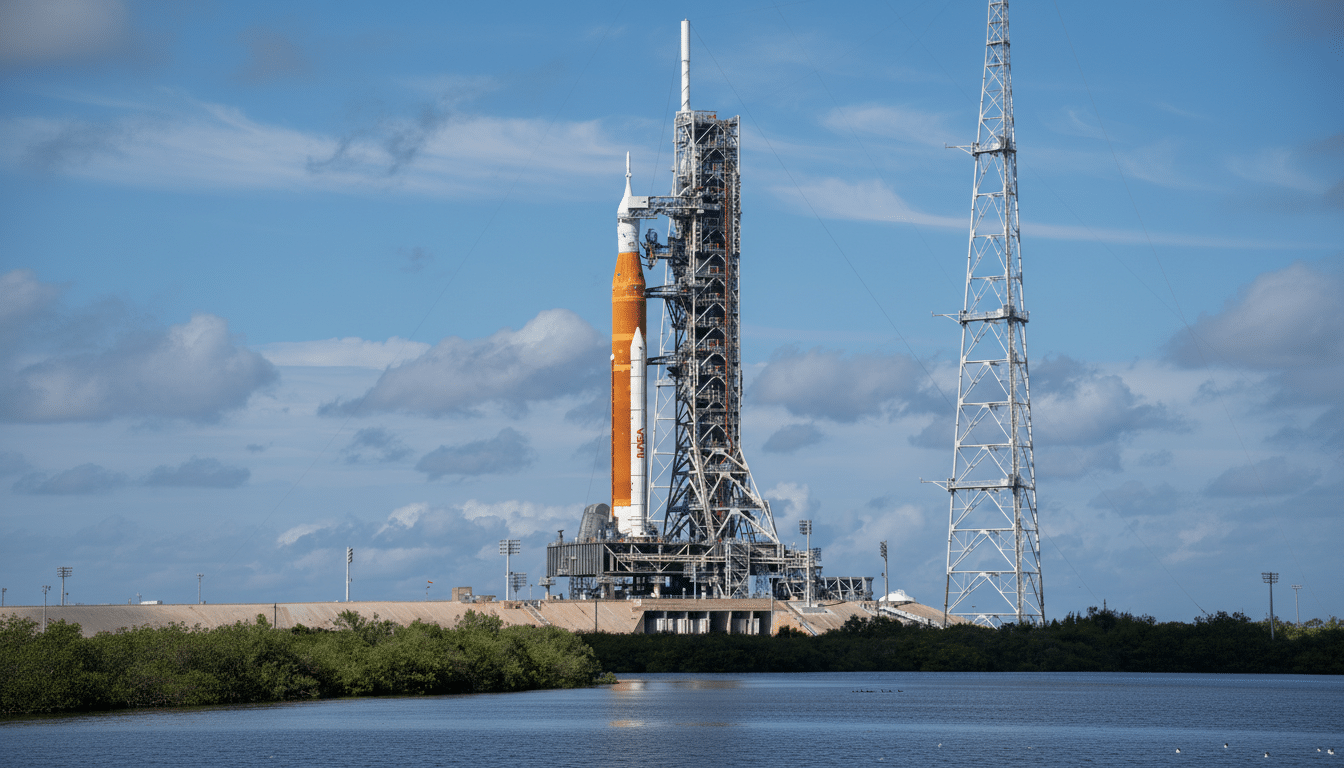

Day 1 begins atop the Space Launch System, whose twin boosters and quartet of RS-25 engines generate more than 8.8 million pounds of thrust. After booster separation and core stage cutoff roughly eight minutes into ascent, the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage finishes the push to Earth orbit with Orion attached.

Once Orion separates, the crew conducts a proximity-operations demo by manually steering back toward the departing upper stage as a stand-in “target.” Johnson Space Center controllers treat this as a rehearsal for the rendezvous and docking work that will be required at the moon on later missions, including linkups with a human landing system or the lunar Gateway.

Flight dynamics keep the early orbit deliberately high and elliptical, a safety cushion that allows a rapid return if systems misbehave. This phase is about proving the basics in space: power, thermal control, avionics, and crew displays, all before committing to the moon.

Nighttime orbital burn and life support system trials

In the first full day aloft, Orion executes a key engine firing to raise the low point of its orbit—timed by orbital mechanics, not convenience. The crew simultaneously checks the Environmental Control and Life Support System, monitoring cabin pressure, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, humidity, and water production under real crew metabolic loads.

Communications and navigation testing then stretch beyond the reach of GPS and near-Earth relay satellites. Tracking swings to NASA’s Deep Space Network, whose 70-meter antennas in Goldstone, Madrid, and Canberra will carry most of the mission’s voice, telemetry, and ranging, a crucial proving ground for sustained operations far from Earth.

Translunar injection burn and resilient free-return path

With systems green, a long burn known as translunar injection commits the crew to deep space. The trajectory is a free-return: gravity alone will arc Orion around the moon and bend it back toward Earth even if later engine firings are unavailable. NASA favors this profile for its built-in resiliency, a lesson embedded since Apollo.

During the roughly four-day cruise, small course-correction burns trim the path while the astronauts rehearse emergency procedures and evaluate radiation-protection techniques inside the cabin. Building on lessons from Artemis I’s sensor-laden mannequins, the crew will try a “storm shelter” configuration using stowed equipment to add shielding against solar particle events.

Far side lunar pass and potential distance record

Late on Day 5, Orion enters the moon’s gravitational sphere of influence and arcs over the far side at an altitude targeted between about 4,000 and 6,000 miles above the surface, depending on launch geometry. For roughly three-quarters of an hour behind the lunar limb, line-of-sight communications will drop, a planned blackout managed by DSN handovers and onboard autonomy.

This is the photo-op and milestone moment: with the moon framed large in the windows, Orion is expected to edge past the Apollo 13 record of about 248,655 miles from Earth. The crew will document the far side—terrain Apollo astronauts never saw—while mission controllers track spacecraft behavior without ground contact.

Coast home, atmospheric reentry, splashdown and recovery

After the swingby, no major braking burn is required. The combined pull of Earth and moon guides Orion onto its homebound leg. Additional manual-flying exercises and systems checks continue en route, along with trajectory tweaks to hit the reentry corridor precisely.

Approaching Earth, Orion jettisons its service module, exposing the heat shield for atmospheric entry at roughly 24,500 miles per hour. Plasma sheaths the capsule, briefly cutting radio contact, as temperatures peak near 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. A sequence of drogues and three main parachutes then slows the vehicle for splashdown off the Southern California coast, where U.S. Navy amphibious teams aim to secure capsule and crew within about two hours.

Why this timeline matters for Artemis lunar ambitions

Every block of this itinerary maps directly to future needs: precision piloting readies crews for rendezvous with a lunar lander, life-support trials buy down risk for longer stays, and deep-space comms prove the ground architecture that will support the Gateway. NASA’s flight directors and the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel have stressed that crewed certification hinges on these demonstrations, from avionics performance to heat shield margins.

Artemis I showed Orion could endure deep space without a crew, logging more than a million miles and a distant lunar orbit. Artemis 2 is the human-in-the-loop exam. If it runs this playbook cleanly—from the first manual fly-around to the last parachute reefing—it clears the path for the first lunar landing attempt of the program and, ultimately, a sustainable cadence of missions that return humans to the moon’s surface.