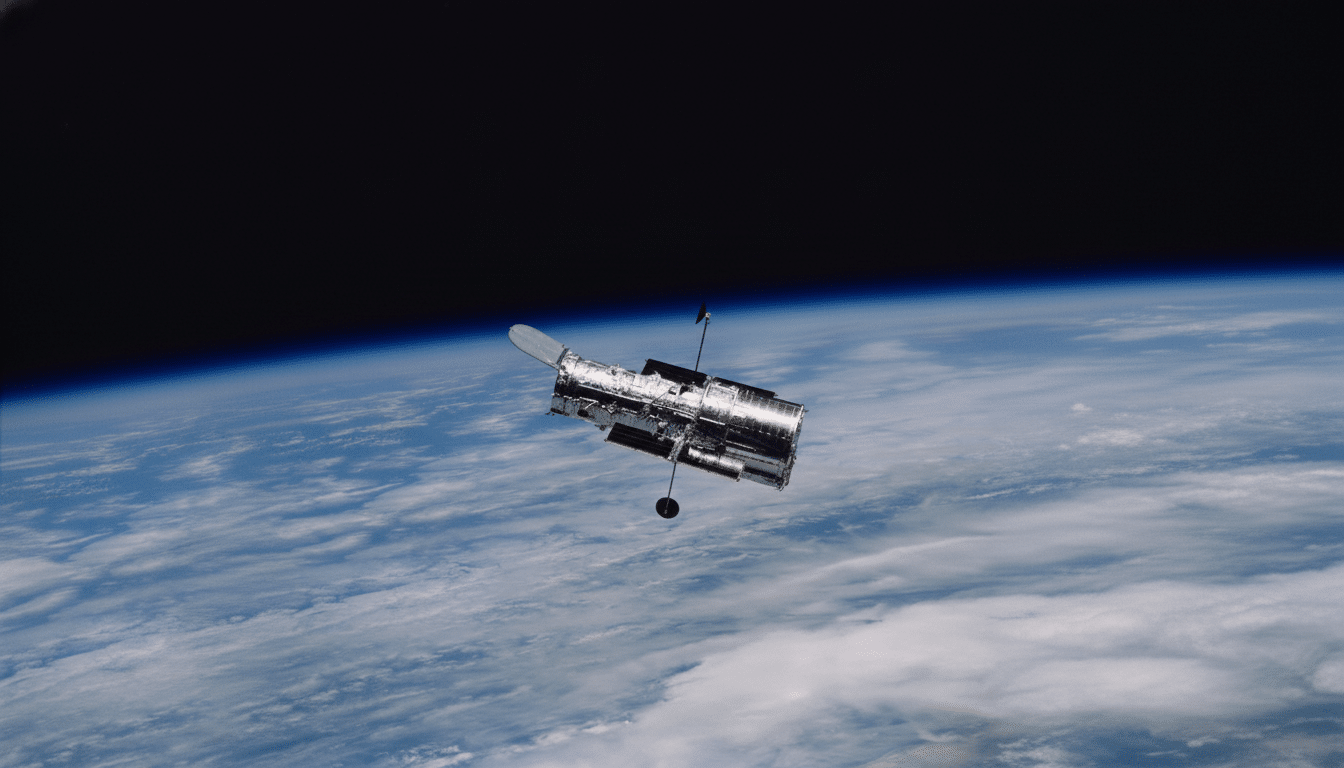

NASA has published a sweeping new collection of images of the comet 3I/ATLAS, a visitor from beyond our solar system that has an increasingly long tail and whose unique chemistry is turning what was to have been a once-in-a-decade scientific opportunity into a visual spectacle. Snapped by a coordinated fleet that includes the Hubble Space Telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and deep-space probes Lucy and Psyche, these views provide an unprecedented look at an interstellar comet zooming through the inner solar system for what may be its only trip here before returning to sunless oblivion.

What NASA’s cameras reveal about interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS

From visible light to near-infrared wavelengths, the images reveal a compact Sun-orbiting nucleus buried in bright coma, spewing jets of vaporizing ices into space along the tail. Webb’s infrared instruments tease out the heat signature from gases and dust, while Hubble’s sharp optical views trace fine strands of particulate material being spewed off the nucleus. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, looking from an entirely different direction, offered one of the closest views yet — at some 19 million miles or so — discerning the compacted inner coma of the comet against a background of stars.

- What NASA’s cameras reveal about interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS

- A rare visitor from beyond our solar system explained

- Chemistry That Thumbs Its Nose at Local Norms

- A coordinated, all-angles campaign across NASA missions

- Why these images matter for comet science and discovery

- Slicing through assumptions with data from many telescopes

Though it appears tranquil, this object is in a rush. Current tracking puts 3I/ATLAS on a hyperbolic path, speeding away at approximately 137,000 miles per hour. It will not be caught by the Sun’s gravity. Its flyby is a one-time performance, and the closest it will come to Earth is a perfectly safe distance of about 170 million miles.

A rare visitor from beyond our solar system explained

Scientists have only confirmed two other interstellar interlopers: 2017’s cigar-shaped, coma-free object called ’Oumuamua and the more traditional, dusty 2I/Borisov in 2019. Comet 3I/ATLAS is the third newcomer to this elite club. Its path and velocity reveal that it formed near another star before being kicked out — probably by the gravitational yank of a giant planet or a passing stellar neighbor — and has been streaking its way through the galaxy’s dark between-the-stars space for eons.

NASA officials stress that the findings are consistent with a naturally occurring comet. The object acts much as comets we are familiar with do — outgassing once it warms up and creating a tail that aligns under the influence of sunlight and the solar wind — but its chemistry is refreshingly alien, like a fingerprint from the planetary nursery where it formed.

Chemistry That Thumbs Its Nose at Local Norms

Early analyses suggest a carbon dioxide–to–water ratio that doesn’t match what’s seen in many solar system comets. Infrared spectra also suggest peculiar dust signatures and trace metals that don’t neatly fit into the averages chronicled by previous flyby missions (like ESA’s Rosetta or NASA’s Deep Impact). The point is those differences: An interstellar comet should be a sample of another planetary system deposited on our doorstep, allowing researchers to test how protoplanetary disks elsewhere build planets and snag ices.

Comparative data matter. ’Oumuamua puzzled observers for not having an obvious coma, while 2I/Borisov appeared to be chemically similar to indigenous comets. By comparison, 3I/ATLAS appears poised to strike a balance — iconically comet-like in shape and presumably unusually composed. That mix will allow modelers to better hone estimates about how volatile inventories fluctuate throughout stellar neighborhoods.

A coordinated, all-angles campaign across NASA missions

Organizing this shoot is a logistical tour de force. The comet is observed by each spacecraft from a different location and with different constraints. Hubble can take high-resolution pictures in visible wavelengths; Webb can slice light into spectra, revealing the presence of molecules; Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s camera is more powerful than those we have in Earth orbit, and it affords us geometry we could never achieve from Earth; and en route missions like Lucy and Psyche will be able to snap an opportunistic picture with instruments designed for asteroid flybys. It’s like seeing a fast pitch from multiple seats around a stadium: no single view is perfect, but together they convey the whole story.

The result is a multilayered data set, from broadband images to spectral fingerprints, which will eventually be archived in NASA’s Planetary Data System for researchers everywhere.

Observations from the Space Telescope Science Institute, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and university teams already are cross-calibrating results to follow how the coma and tail evolve in response to varying solar heating.

Why these images matter for comet science and discovery

Interstellar comets are the closest we will ever come to a laboratory sample from another star system that we can study here on Earth at scale today. By mapping the volatile mix in 3I/ATLAS, researchers can test theories of planet formation, migration, and disk chemistry outside our Sun. How it works will guide future telescopes — including the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s sky survey and NASA’s NEO Surveyor mission — that are planned to increase the discovery rate and the likelihood of catching these rare messengers from (astronomically) nearby stars.

For the public, the images are a poignant reminder that our solar system is not insular. We can measure the light out there and marvel at the pictures. The science is rigorous; the perspective could not be more inspiring.

Slicing through assumptions with data from many telescopes

Like any dramatic celestial event, rumors have circulated. The NASA approach has been simple: point as many instruments as possible at the object, publish the data, and let the measurements talk. Everything that was observed — its orbit, outgassing, and spectral lines — is consistent with what one would expect for a natural comet on a one-time interstellar flyby. The remarkable thing isn’t that it’s artificial; it’s that the alien is real.

The window is brief. 3I/ATLAS is currently bright but getting dimmer as it moves off into deep space. That urgency is the reason this cross-mission image release is important. It’s more than a gallery; it’s a testament to the moment we planted our instruments between stars and recorded that traveler in unflinching detail.