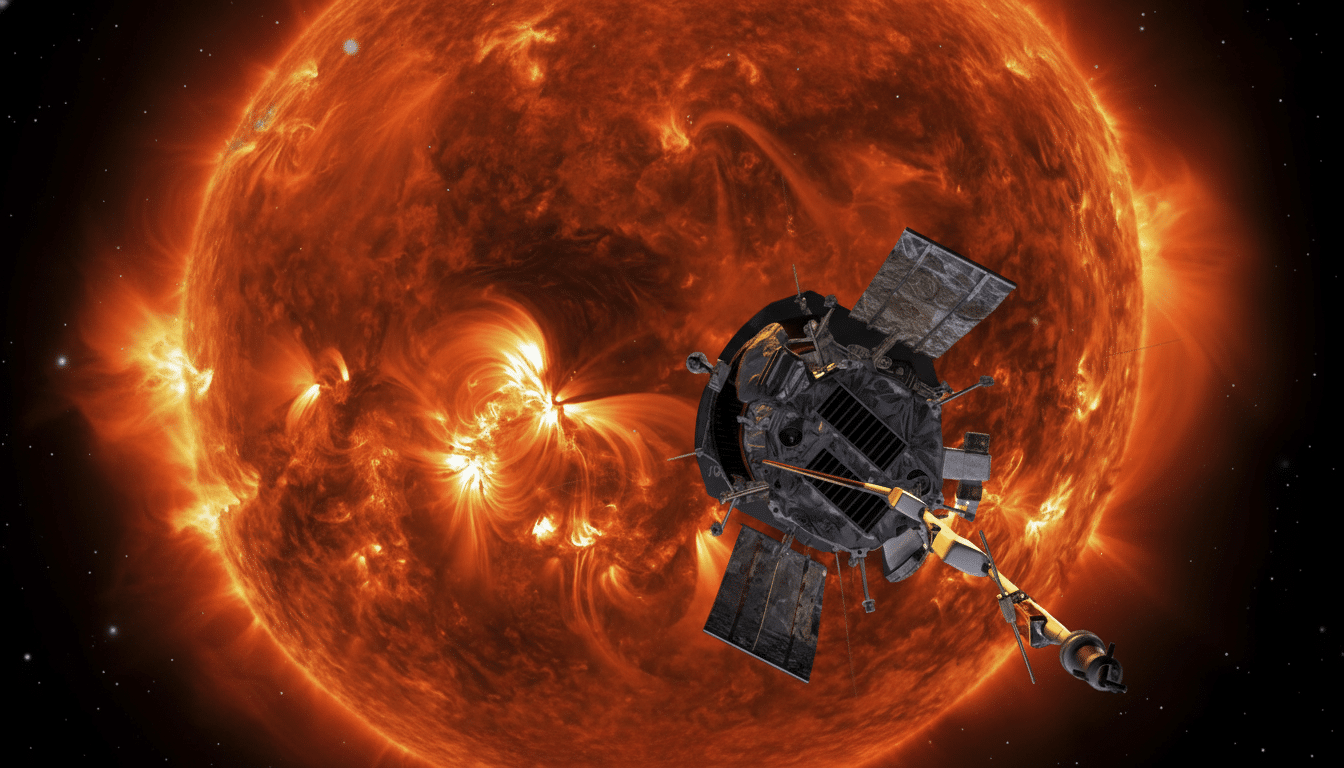

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is hurtling through the Sun’s wispy outer atmosphere today and has circled the visible surface in more ways than one as it continues its record-breaking speed as the fastest human-made object, traveling about 3.8 million miles from the star itself. This near brush is the latest in a series of bold dives that aim to grab hold of the raw physics of the corona, the superheated sheath that sows the solar wind and powers space weather rippling across Earth.

How fast and how close Parker Solar Probe travels at perihelion

At perihelion, when the probe is at its nearest point in its elongated orbit, it’s traveling at a blistering 430,000 miles an hour — so fast that you could travel from New York City to Tokyo in well less than a minute.

That quickness is thanks to a sequence of Venus gravity assists, each one continuing to cinch up the spacecraft’s orbit and stepping it farther down toward the Sun. The approach range, around 3.8 million miles from the photosphere, will put Parker directly in the path of the corona, where temperatures can climb into the millions of degrees Fahrenheit.

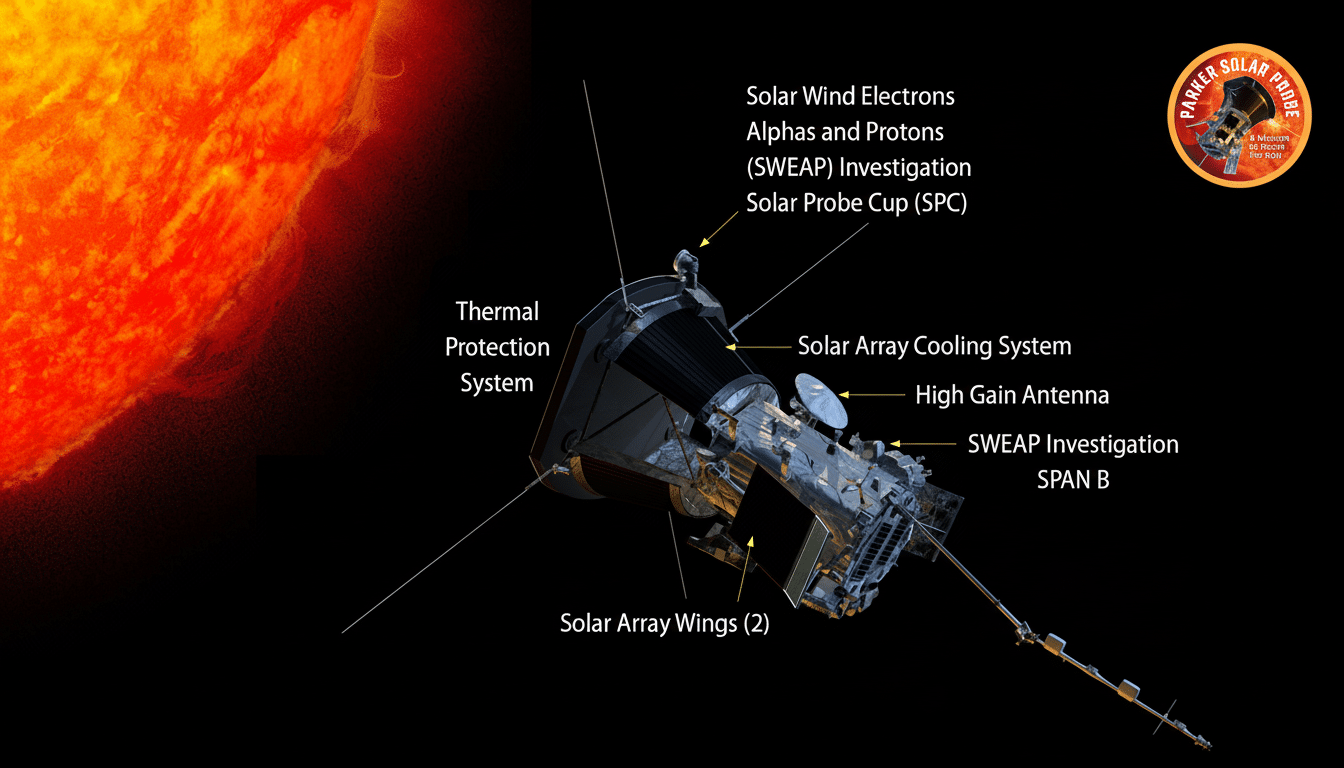

Survival at these extreme temperatures comes down to a tough carbon–carbon heat shield that NASA has dubbed the Thermal Protection System. Even as the shield absorbs temperatures of nearly 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit, the spacecraft’s body behind it will hover around room temperature, so its instruments can sample the solar environment in never-before-seen detail.

Why the Parker Solar Probe must pass through the corona

The Sun’s corona is a paradox — it is thousands of times hotter than the cooler layer at its surface, and it spews out charged particles in what becomes the solar wind. The boundary at which material finally escapes — the Alfvén surface — has been a theoretical line on a chart for many years. Parker’s passes are transforming that abstraction into a map, revealing that this boundary is not a smooth, even surface but jagged, expanding and contracting along with solar activity.

Swimming within these stormy seas, the probe has also sampled the fingerprints of “switchbacks” — whiplike kinks in magnetic fields — and monitored how eruptions either escape into interplanetary space or fall back and crash into the Sun’s atmosphere. Recent findings published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters point to a complex process — magnetic recycling that can reshape future eruptions — an insight that shores up the connection between what erupts on the Sun and what arrives at Earth.

What the Parker Solar Probe instruments are hunting for

Parker’s quartet of instruments is designed to track down the Sun’s most elusive signals:

- FIELDS measures electric and magnetic fields, identifying the location of wave activity and how the corona’s tangled strands of magnetism twist around one another.

- SWEAP (Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons) samples and analyzes charged particles, showing how the solar wind is heated and accelerated.

- The Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun detects energetic particles that are sent off through space and can hit spacecraft and astronauts with very little warning.

- WISPR, a visible-light imager, looks out sideways from the Sun shield to see the flowing solar wind and the ghostly, encircling halos of CMEs as they first begin to form.

Together, these measurements help complete the picture from the surface of the Sun to the huge flow of plasma and fields that fill the heliosphere.

Coordinated observations with spacecraft such as ESA’s Solar Orbiter are giving us vantage points Parker cannot access on its own.

Space weather stakes for Earth’s technology and safety

But space weather is about more than auroras. Powerful solar flares and coronal mass ejections can interfere with long-range radio communications, affect GPS accuracy, cause polar airline reroutes, and stress electric grids. The 1989 power failure in Quebec and the destruction of dozens of newly launched satellites during a geomagnetic storm in 2022 serve as stark reminders. Parker’s data are already refining models — such as those employed by the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center to predict these energetic, solar-flung particles and by mission planners for long-duration, deep-space operations.

For human exploration, the implications are clear. The heliophysics community within NASA cites Parker’s contributions in helping to ensure the safety of Artemis crews as they journey beyond Earth’s protective magnetic envelope, where advance notice and better knowledge of solar wind conditions can mean the difference between routine operations and greater risk.

What’s next for the mission as the solar cycle shifts

With every new orbit, Parker travels farther into uncharted space as the Sun’s magnetic fields move from the activity peak of Solar Cycle 24 toward the valley of Solar Cycle 25, when conditions should be much quieter. That changing canvas is important: the structure of the corona, the frequency of switchbacks, and the location of this Alfvén surface all shift with the solar cycle, providing a natural laboratory for scientists to investigate how storms are born in active times and how wind works when it’s still.

NASA and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, which operates the mission, are considering a plan for future operations that would squeeze even more science from the spacecraft’s remaining life. For now, at least, it is exactly where heliophysicists have yearned to go for decades — airborne in the furnace, turning many of the most enduring mysteries chronicled by our star into measurable facts and providing a better early-warning system on Earth in the process.