NASA is preparing to undock SpaceX’s Crew-11 Dragon from the International Space Station for a rare medical evacuation, bringing four astronauts back to Earth earlier than planned. Agency officials say one crew member developed a serious but stable medical issue that warrants a full diagnostic assessment on the ground, triggering a “controlled expedited return” rather than an emergency deorbit.

The operation marks the first medical evacuation in the station’s quarter-century of continuous operations, underscoring both the maturity of commercial crew transport and the limits of in-orbit health care. NASA has not identified the affected astronaut, citing medical privacy. Japan’s space agency has stated publicly that JAXA astronaut Kimiya Yui is not the individual involved.

Why NASA Is Calling It A Controlled Expedited Return

Unlike an emergency deorbit, a controlled expedited return adheres to standard undocking, reentry, and splashdown rules while moving up the timeline. That means Dragon will depart the station during an available orbital window, aim for an approved splashdown zone in the Pacific off California, and proceed only if weather and recovery conditions meet strict criteria for winds, seas, and visibility.

NASA flight surgeons are embedded with recovery teams, and regional hospitals are placed on standby as part of the standard post-landing medical pathway. The agency emphasized that the crew member’s condition is stable, and the decision prioritizes rapid access to advanced imaging, lab work, and specialist care not available in orbit.

What To Expect During Dragon’s Trip Home

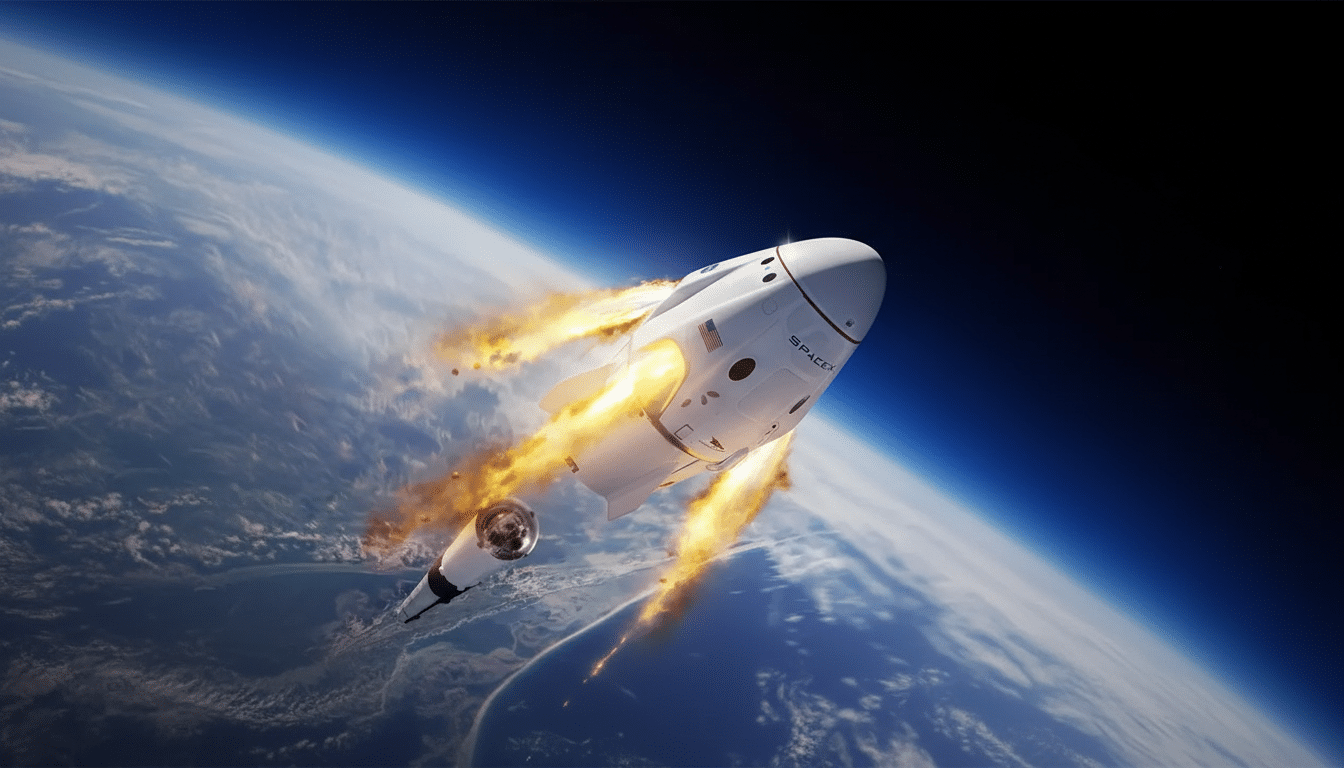

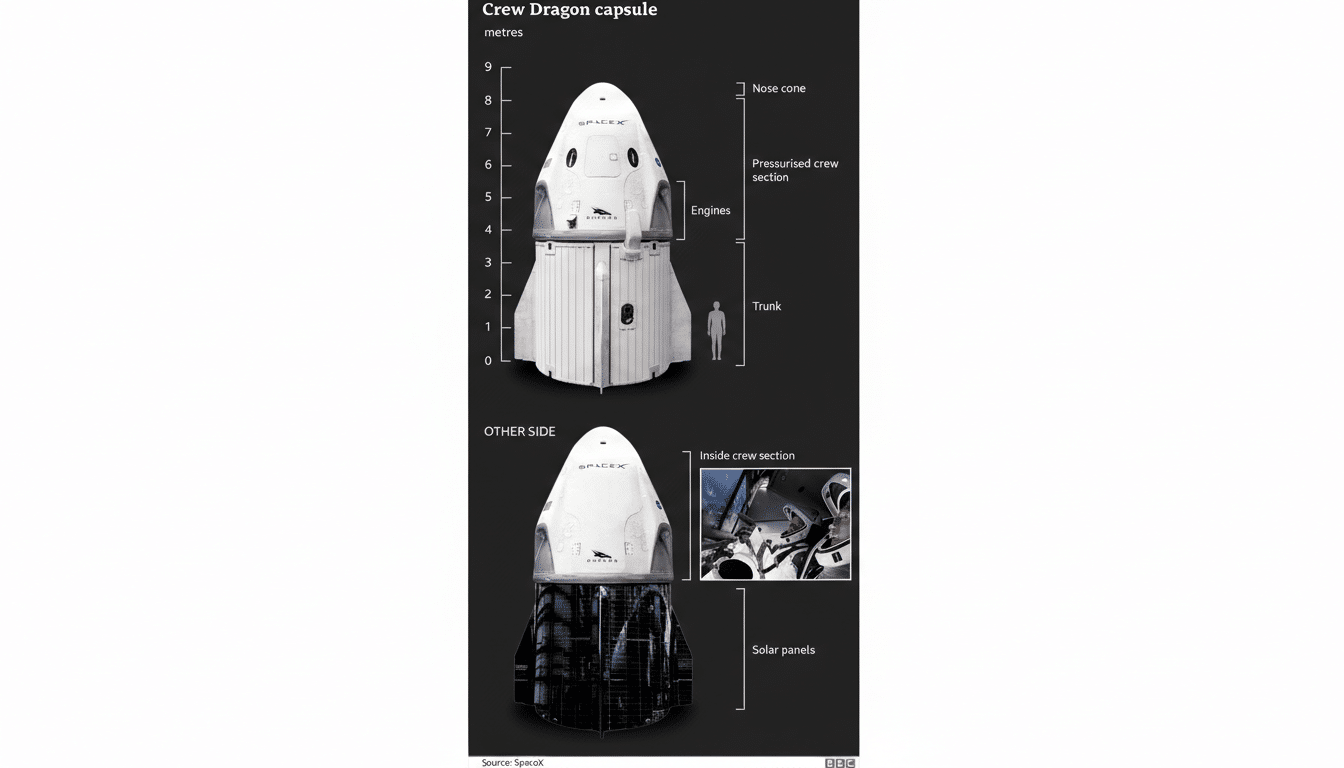

After hatch closure and undocking, Crew Dragon executes a series of departure burns to safely separate from the station, followed by a deorbit burn that commits the vehicle to reentry. The trunk is jettisoned, plasma blackout temporarily interrupts communications, and the capsule endures peak deceleration that typically tops out around 4 g before deploying drogue and main parachutes for ocean splashdown.

SpaceX recovery vessels track the capsule’s descent, secure it to the deck, and offload the crew within minutes of splashdown. Medical evaluations begin immediately in a dedicated onboard clinic, with the option for rapid transport to shore-based facilities if doctors determine further intervention is needed.

Medical Care Limits Aboard the International Space Station

The ISS carries a robust medical kit, automated external defibrillator, and ultrasound equipment, and astronauts train extensively in advanced life support. But the station lacks CT scanners, comprehensive lab diagnostics, and surgical capability. NASA’s Human Research Program and National Academies assessments have long flagged conditions that are difficult to manage in space, including cardiac arrhythmias, kidney stones, infections, and neurological or ophthalmic issues.

Vision changes linked to spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome have been observed in roughly 60–70% of long-duration flyers, and case studies have documented unexpected vascular findings that required careful, ground-guided monitoring. Telemedicine can bridge some gaps—ultrasound scans are often performed with real-time coaching from Earth—but the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment still resides in terrestrial hospitals.

Who’s Coming Home and Who Stays Aboard the Station

Crew-11 consists of commander Zena Cardman, pilot Mike Fincke, JAXA astronaut Kimiya Yui, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Oleg Platonov. NASA says the medical concern is unrelated to station systems, spacewalk preparations, or a work-related injury; a planned spacewalk was canceled while teams refined the return timeline.

After Dragon departs, American astronaut Chris Williams—who arrived on a Russian Soyuz—will remain the sole U.S. crew member on orbit, supported by Russian colleagues. Critical station maintenance and science operations will continue, though some activities may be reshuffled until the next crew rotation arrives once flight readiness and range availability align.

Operational Risks And Recovery Readiness

Weather is the biggest variable for splashdown operations. Recovery teams assess sea state, precipitation, lightning risk, and offshore winds at multiple sites before committing to reentry. SpaceX and NASA have repeatedly demonstrated the ability to wave off and reattempt when conditions improve, prioritizing crew safety over schedule.

Operationally, Dragon’s autonomous systems and redundant flight computers are designed to handle contingencies. The vehicle’s environmental controls can be tuned to accommodate medical needs during descent, and onboard supplies include oxygen, intravenous fluids, and medications under a physician-directed protocol.

How to Follow the Return and Live Coverage Updates

NASA plans live coverage of hatch closure, undocking, deorbit, and splashdown across NASA Television and official social channels, with a post-landing briefing once the crew is aboard the recovery ship. Because timelines can shift with weather and orbital mechanics, the agency advises watching for schedule updates as departure approaches.

This medical evacuation will be closely watched across the aerospace and medical communities. It is a consequential demonstration of how commercial spacecraft, space station partners, and flight surgeons work in concert when the safest place for an astronaut is back on Earth.