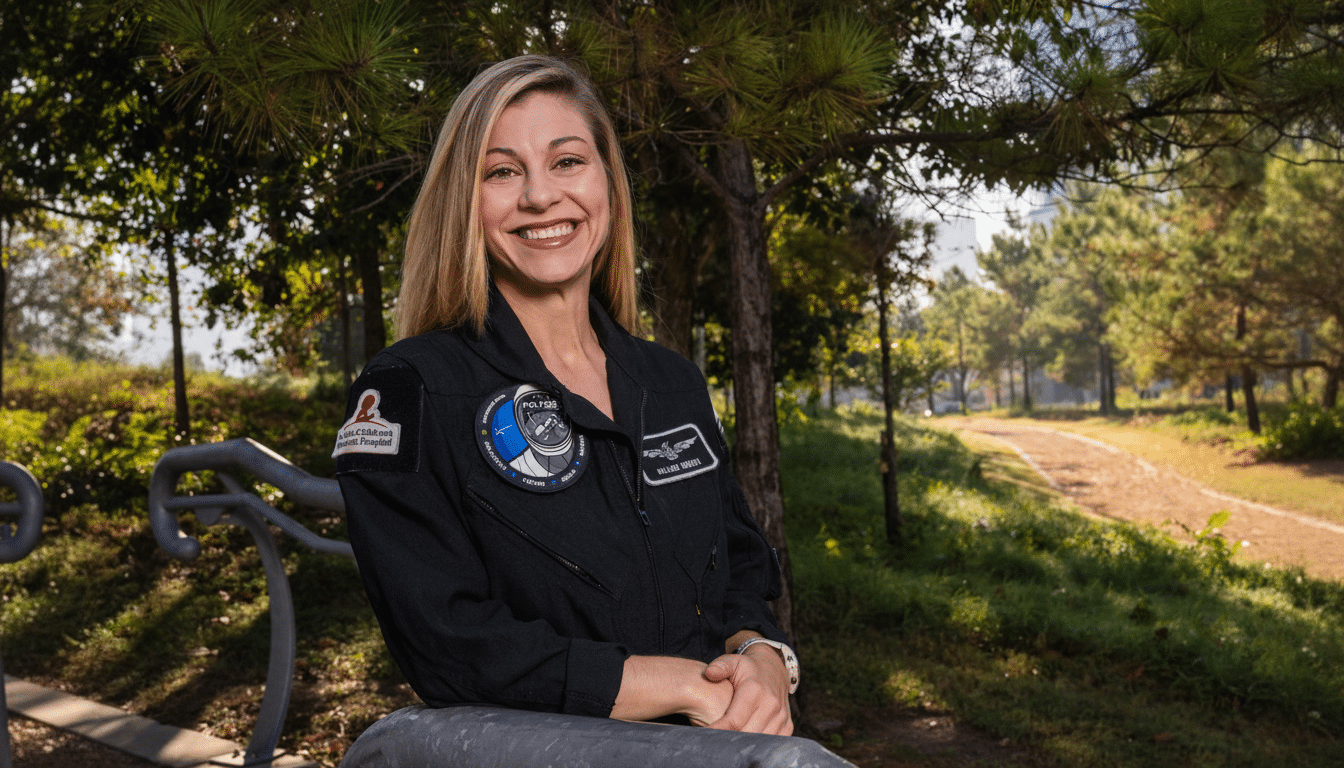

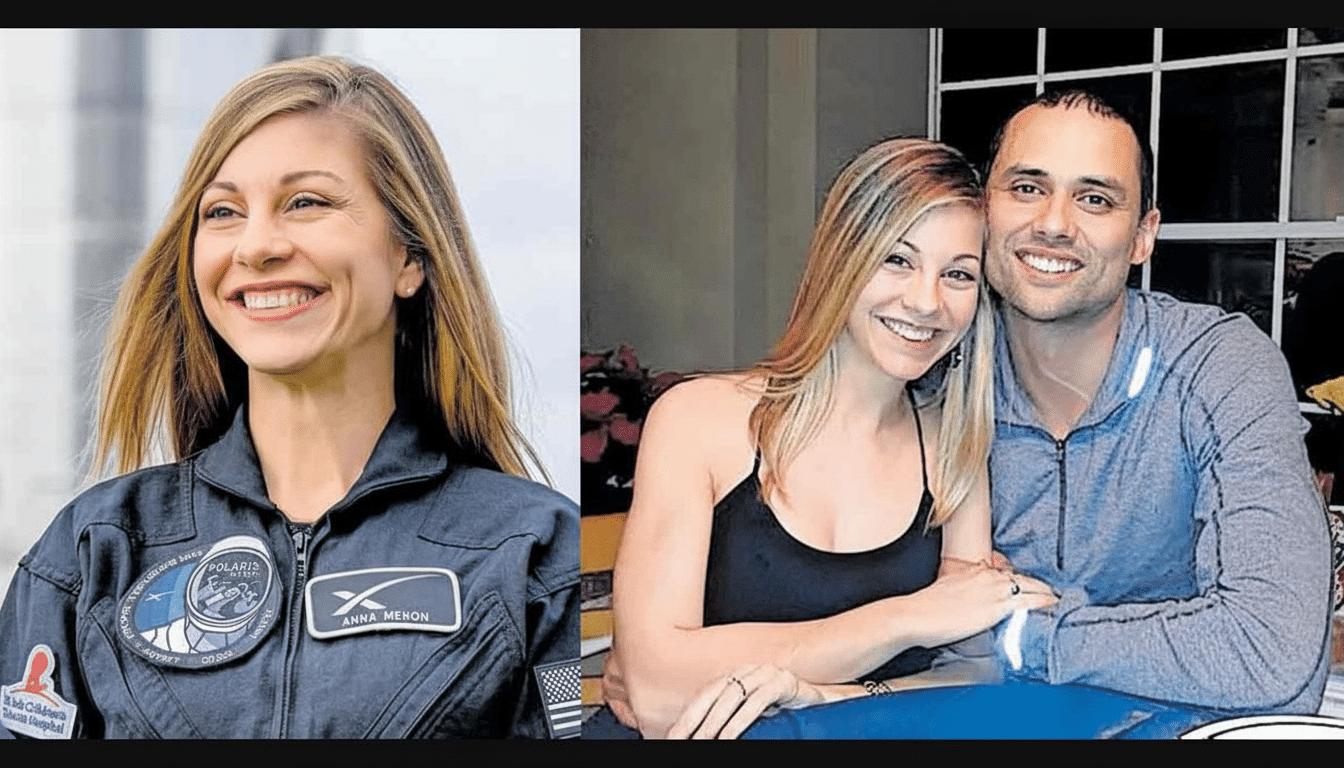

Two names well-known to commercial space insiders are included in NASA’s newest group of astronauts: Anna Menon and Yuri Kubo. Both developed extensive operational résumés, grew from experience that was now coming to the fore of human spaceflight closer to home; how it is a make-or-break skill among high-level American astronaut recruits.

Who Are Anna Menon and Yuri Kubo, the SpaceX veterans?

Anna Menon straddles NASA and SpaceX cultures in a way few candidates can. She began her work at NASA’s Mission Control Center providing biomedical support and then went to work at SpaceX as a senior engineer working on private astronaut missions. She then flew as a mission specialist and medical officer on the Polaris Dawn mission, which featured the first commercial spacewalk and road-testing of SpaceX’s EVA suit and procedures in a challenging real-world context.

Yuri Kubo offers high-rate launch and systems integration experience.

Kubo spent over a decade at SpaceX, where he was a launch director for Falcon 9 and held senior roles related to the company’s ground systems and its Starshield program. That work is the operational underpinning of modern spaceflight: managing the complicated sequence of events that lead to liftoff, certifying readiness across a phalanx of hardware and software, and knitting together teams scattered between control rooms and test sites and recovery assets.

Why SpaceX experience matters for NASA’s astronaut corps

NASA chose just ten of over eight thousand applicants — an acceptance rate of less than one-tenth of one percent. With a pool that competitive, the amount of hands-on time with a crew-rated vehicle and high-cadence operations sets the company apart. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon has become NASA’s main taxi to low Earth orbit, and the company has also flown several private astronaut missions. Engineers and operators who have lived that tempo know the margins of failure, crew interfaces, turnaround constraints in a way that can help shrink learning curves inside NASA.

Such medical and EVA experience is particularly rare for an astronaut like Menon. Spacewalks — commercial or government — are some of the most dangerous things we do in human spaceflight. Procedures, suit integrity, stress-impacted physiology and emergency choreography must follow in close coordination. “While NASA continues work to refine the concepts of lunar surface and cislunar EVA under the Artemis architecture, having an astronaut candidate who has already been involved in a commercial EVA campaign directly informs our experiences from that operation.”

Kubo’s launch and ground-systems leadership corresponds to the operational backbone of any exploration effort. The rhythm that SpaceX created with Falcon 9 has reimagined prelaunch checks, anomaly triage and recovery efforts. Alternatively, reports and independent studies drawing on input from NASA’s own safety advisers for the space agency (such as the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel) have stressed the importance of strong, repeatable processes to help mitigate risk as mission complexity increases. “For the candidates who have done dozens of countdowns, that regime comes with them,” he said, and they apply it to procedures in the astronaut office and mission planning.

Training and missions ahead for newly selected astronauts

Upon assignment, new astronaut candidates will spend approximately two years in training. NASA’s program includes robotics work with Canadarm2, extravehicular activity training in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, T-38 jet training to sharpen crew resource management, space medicine, systems engineering and geology for planetary science as well as survival courses. Language skills and international partner ops are still handy for long missions.

Following graduation, the class is eligible for flights to the International Space Station and, increasingly, fields associated with the transition toward commercial low Earth orbit activities.

NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations program was formed in hopes of replacing the aging government-owned landmark with commercial stations. The handover will require careful schedule management, independent reviews by the Government Accountability Office and NASA’s Office of Inspector General have concluded. Astronauts who are willing to work well in that intersection between agency requirements and industry practices will be essential in ensuring a seamless changeover.

Further down the line, missions to the Moon will require cross-disciplinary skills. A medical background is applicable for supporting long EVA suit runs, pressurized suits and life support experience certainly is relevant, as is the instinct of an operator to know how devices should be designed. Menon’s and Kubo’s experience matches those demands; one comes from a background of human performance, in-space operations and the other with knowledge in launch, integration and ground-to-orbit systems.

A wider shift in astronaut recruiting as commercial space grows

For decades, astronaut classes were filled with test pilots, academics and government laboratory researchers. That mix is shifting as commercial partners take on a larger share of the work in Earth orbit and beyond. SpaceX alumni have made this jump in the past — examples include Robb Kulin and Anil Menon — and the trend is broadening as private missions evolve from displays of capability to routine operations.

The end result is a two-way talent pipeline. NASA saves significant time having operators who are already familiar with Dragon-era mission norms and industry sees savings by employing personnel well-versed in safety culture and NASA’s certification pathways. Once the Artemis program and some of the new commercial station initiatives start to take shape, that common language might be as critical as any new gizmo.

In the case of Anna Menon and Yuri Kubo, NASA is not only welcoming aboard two experienced professionals. It is codifying a model where commercial flight experience is not just an edge but a core credential for the next generation of explorers.