Austria’s armed forces have received the green light to complete a full transition from Microsoft Office to the open-source suite LibreOffice, with delivery now planned before year-end. It is one of the largest transitions in Europe for an agency that employs over 20,000 staff.

Officials said the decision was not motivated by licensing costs, but a strategic objective of digital sovereignty and insight into every scrap of sensitive data.

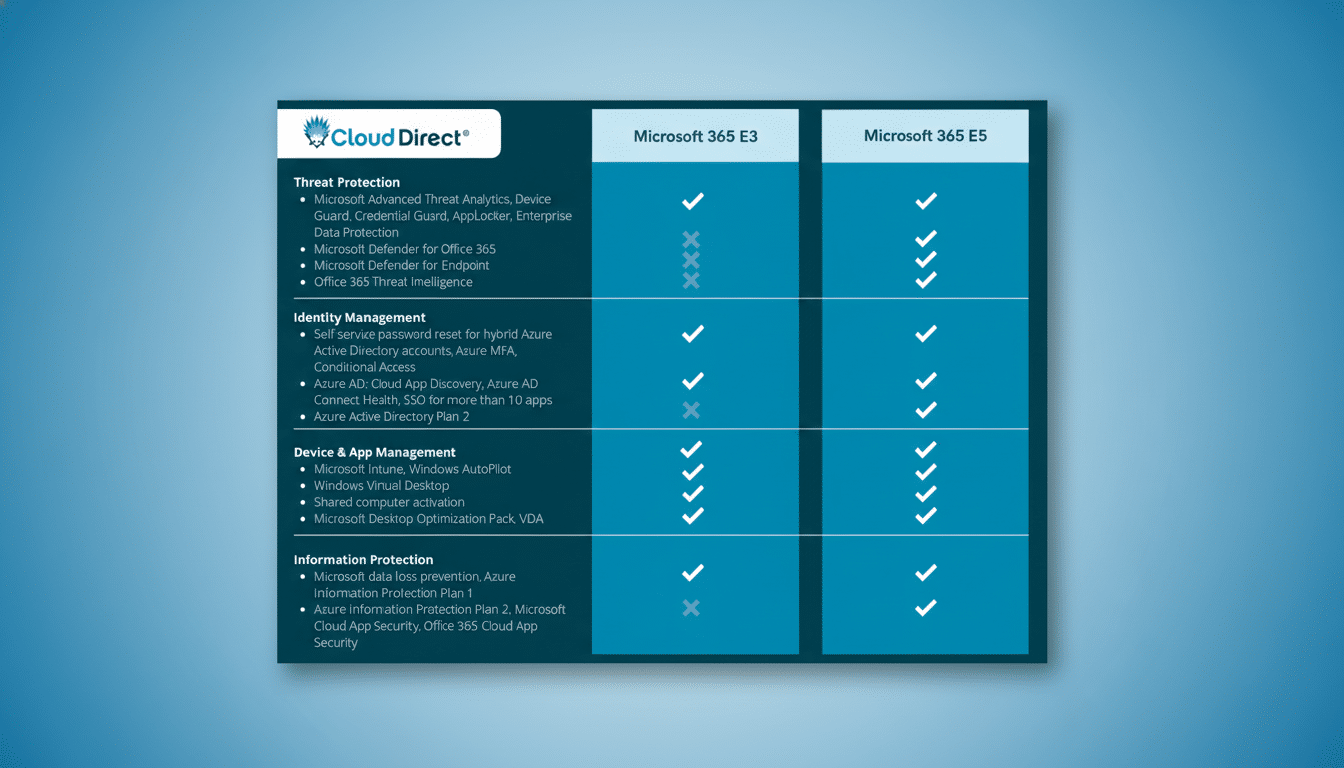

All of that is striking math nonetheless. At the average Microsoft 365 E3 list price of approximately $33.75 per user per month, those 16,000 seats represent roughly $6.5 million in annual business. LibreOffice is a free-of-charge application suite, but the ministry emphasises that freedom from foreign cloud dependencies and being able to lock down more in-house computing are really the returns.

Why Digital Sovereignty Was The Key To Making A Difference

The project was presented by Austria’s Directorate 6 for information and communications technology and cyber defense as an attempt to test national resilience. The goal: minimize exposure to extraterritorial laws or vendor lock-in, and maintain documents and metadata on infrastructure wholly controlled by the state.

European regulators have sounded alarms over the risks of cross-border access to data. The Court of Justice of the European Union’s seminal judgment on transatlantic data flows, guidance from the European Data Protection Board, and broader concerns about the U.S. CLOUD Act have all prompted public authorities to re-evaluate their use of non‑EU-based platforms. Even when large vendors promise to protect customers, officials say the only truly robust protection is architectural control.

Stewarded by The Document Foundation, LibreOffice is based on the OpenDocument Format which itself is an ISO standard. Standardized formats make “lock‑in” more difficult, improve archivability, and enable governments to change information supply arrangements without having to re-write your playbook.

What the LibreOffice migration involved for Austria’s forces

The military followed a staged rollout: early adopters stepped forward first, then more soldiers after training and after templates and policy baselines had been set. The team received narrowed guidance on Writer, Calc and Impress, but also on the process of working with partners that unfortunately still use DOCX, XLSX or PPTX.

A critical job was translating complicated templates, styles, and macros that had grown over more than a decade of use in Microsoft Office. External experts were hired to harden document models, ensure interchangeability, and construct migration tools that minimized manual rework. Where such gaps did exist, the military paid for upstream features — better slideshow editing or stronger pivot table support — and writes that these additions are now available to all LibreOffice users.

By investing in open-source development rather than proprietary customizations, the ministry now gets features it can audit and control, without creating yet another parallel stack of bespoke add‑ins that only create technical debt.

The cost and the trade-offs of switching to LibreOffice

Licensing savings are the largest line item but not the only one. The forces shifted budget to training, support and change management – where the real game for migrations is won or lost. Local integrators as well as European vendors like Collabora and SUSE are potentially in place to offer enterprise support without adding the lock‑in the project was aiming to remove.

Compatibility remains the perennial concern. More complex documents that were created around older macros, less commonly used fonts, or specialized plugins can be stubborn. The military answered this question with a practical exception policy: highly restricted access to Microsoft Office long-term servicing channel modules for edge cases and continued usage of select tools like Access where mission workflows require it. The default, however, is end‑to‑end OpenDocument.

Part of a wider European trend toward open standards

Austria is not acting alone. The German state of Schleswig‑Holstein has said it will switch to using Linux and the OpenDocument format. Danish officials have indicated that cloud suites to the exclusion of proprietary ones will be ruled out on sovereignty grounds. The French city of Lyon is adding Linux desktops and the open-source office suite LibreOffice to better control the IT infrastructure managing its citizens’ data.

All of this fits into wider currents of EU policy, for example the EC’s Open Source Software Strategy and Interoperable Europe framework, as well as investment in sovereign cloud initiatives like Gaia‑X; national cybersecurity agencies such as Germany’s BSI have also called on critical sectors to cut single‑vendor dependencies for core office and communications tools.

Public bodies have been alerted to high‑profile instances where cloud providers changed or discontinued services in response to regulatory or geopolitical pressure — events reported by leading newspapers and think tanks. The lesson is clear, for all the haters: maintain control of your stack if you cannot tolerate unplanned downtime or get‑rich‑quick policy‑driven change.

What success will look like for Austria’s LibreOffice shift

Metrics of success will be round‑trip fidelity with externals, user satisfaction, response time in incidents, and numbers of documents being stored in ODF rather than proprietary formats.

Equally significant is the human readiness: are my templates clean, can I easily maintain macros, and do users understand collaboration pathways now that a contractor sends them a DOCX document?

If those boxes remain checked, Austria’s action could serve as a template for ministries, municipalities and security services across Europe. The immediate gain is cost predictability, but the ultimate prize is that of freedom to operate — on your terms with software you can see, modify and keep up even when people are pressing from outside.