Microsoft has issued a warning to Azure customers that they can expect to see increased latency, although some may also experience packet loss following multiple breakages in subsea cables between the Red Sea and India, potentially disrupting parts of the global internet infrastructure. The company said it had redirected traffic to steady performance and was continuing to rebalance flows across its global backbone to lessen the effect.

Monitoring groups have also recorded a broader regional deterioration. The independent monitor NetBlocks said simultaneous underwater cable failures in the Red Sea resulted in less connection time for multiple countries like India and Pakistan. Microsoft did not say what had caused the cuts or who was responsible, but noted that undersea repairs may take time.

Where Azure took a hit

Azure traffic in the Middle East or bound for Asia and Europe suffered the most, Microsoft status communications indicated. Customers may have also experienced increased round‑trip times on east‑west workloads, content delivery toward Indian and Gulf markets, and replication between European and Asian regions, as well as VPN tunnels on Suez‑routed transit.

Rerouting adds physical distance. A standard London–Singapore route through Suez typically clocks in around 160–180 milliseconds; run that same traffic around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and latency can hit 250–300 milliseconds. The difference may be sufficient to slow chatty applications, and cross‑region database syncs, and some trading or media workloads, even if uptime is not affected.

Why the Red Sea is a chokepoint

The Red Sea–Suez subsea system is one of the world’s busiest fiber routes from a system count perspective, providing the lowest latency by directly connecting the most-populated and fastest-growing regions along the southern Red Sea with key internet hubs in Europe and India. Hundreds of thousands of kilometers of undersea cables crisscross the globe, industry trackers such as TeleGeography estimate, but only a few strand sets traverse this narrow chokehold. That creates a high‑stakes bottleneck for cloud backbones and content suppliers.

More than 95 percent of the world’s data is transmitted using such cables. Cut several lines in a common trench, and there is an additive effect: capacity collapses very fast, and traffic is pushed through on other routes that were not designed to carry full peak loads, magnifying latency and jitter.

Microsoft’s mitigation playbook

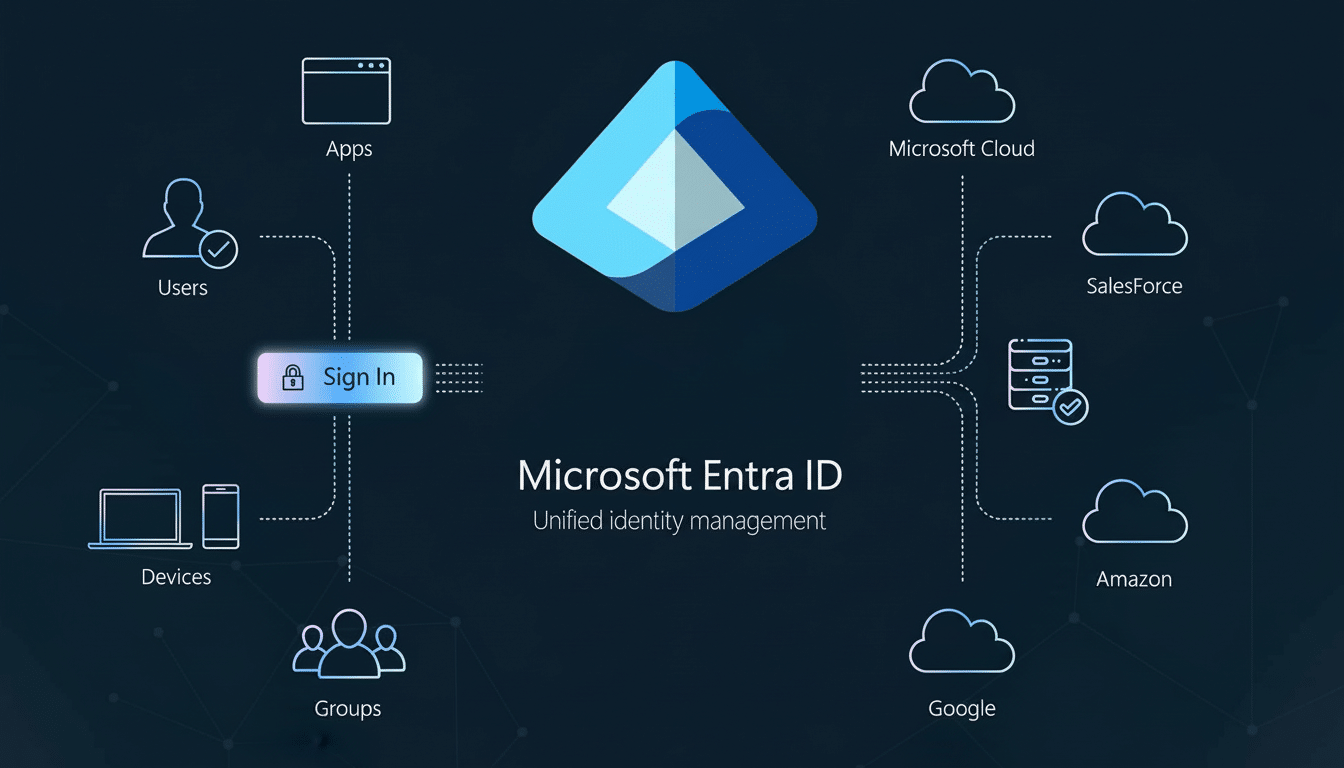

Hyperscalers build for this. Microsoft has a private WAN that interconnects the regions and peers with several carrier‑owned systems. Where there are cable faults, the company employs software-defined traffic engineering (segment routing, fast re‑route, dynamic BGP policies, etc.) to re‑direct flows across surviving Mediterranean, Arabian Sea, and West African paths, including trans‑Atlantic and tran‑sPacific links when necessary.

These steps maintain availability, but cannot violate physics. Customers operating latency‑sensitive workloads between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia may remain affected as traffic is re-routed and capacity in the Red Sea corridor is recovered. To mitigate the impact to performance, organizations can pin traffic to the least‑affected Azure regions, temporarily relax replication SLAs, or have edge caching and read‑replicas closer to the end user.

Attribution is unsettled

Microsoft has not said who or what is responsible for the cuts. Yemeni Houthi movement denies fiber attack Yemen’s Houthi group has denied attacking fiber infrastructure following maritime tensions in the region, the Associated Press has reported. In the past, subsea faults have been more commonly associated with anchors, trawling, earthquakes or landslides, however intentional interference still remains an ongoing issue for operators and governments.

Fixing deep‑water cables is also expensive, requires specialized ships, is done within weather windows and requires coordination with coastal authorities. In politically complicated waters, insurance and security considerations can also slow the clock. Operators splice or test each damaged portion before putting it back into service, so partial restorations might come before the full return to capacity.

Ripple effects beyond Microsoft

While Azure is the most visible service acknowledging the impact, the infrastructure itself is shared across carriers and content networks. Analysis from independent monitors including NetBlocks and regional IXPs indicates that internet transit was congested and BGP routes took longer to propagate as traffic was funneled onto the remaining connections. There are more than a few conduits that other hyperscalers and telcos use, even if they are on separate paths.

What companies should do now

Track end‑to‑end latency, not just availability, across affected corridors. If possible, move latency‑sensitive workloads to regions with predictable paths and minimize Inter‑region chatter. Verify failover policy for VPNs and private peers as some tunnels will prefer inferior paths during global reconvergence. Extend cache TTLs and serve static assets from edge locations closest to users for customer‑facing apps.

And the incident reveals a more fundamental truth: Cloud resiliency is subsea resiliency. Diverse carriers, multi‑region architectures, and well-established incident runbooks are the best defence against chokepoint failures—even when suppliers such as Microsoft move fast to right the ship.