Meta is pushing ahead with Project Waterworth, a globe-girdling undersea system that would run more than 50,000 kilometers and connect five continents. Positioned as the company’s most ambitious cable yet, the build’s goal is to make the world’s backbone more robust in serving AI-era data flows and to increase route diversity on some of the internet’s most fragile corridors.

What Project Waterworth builds in subsea networking

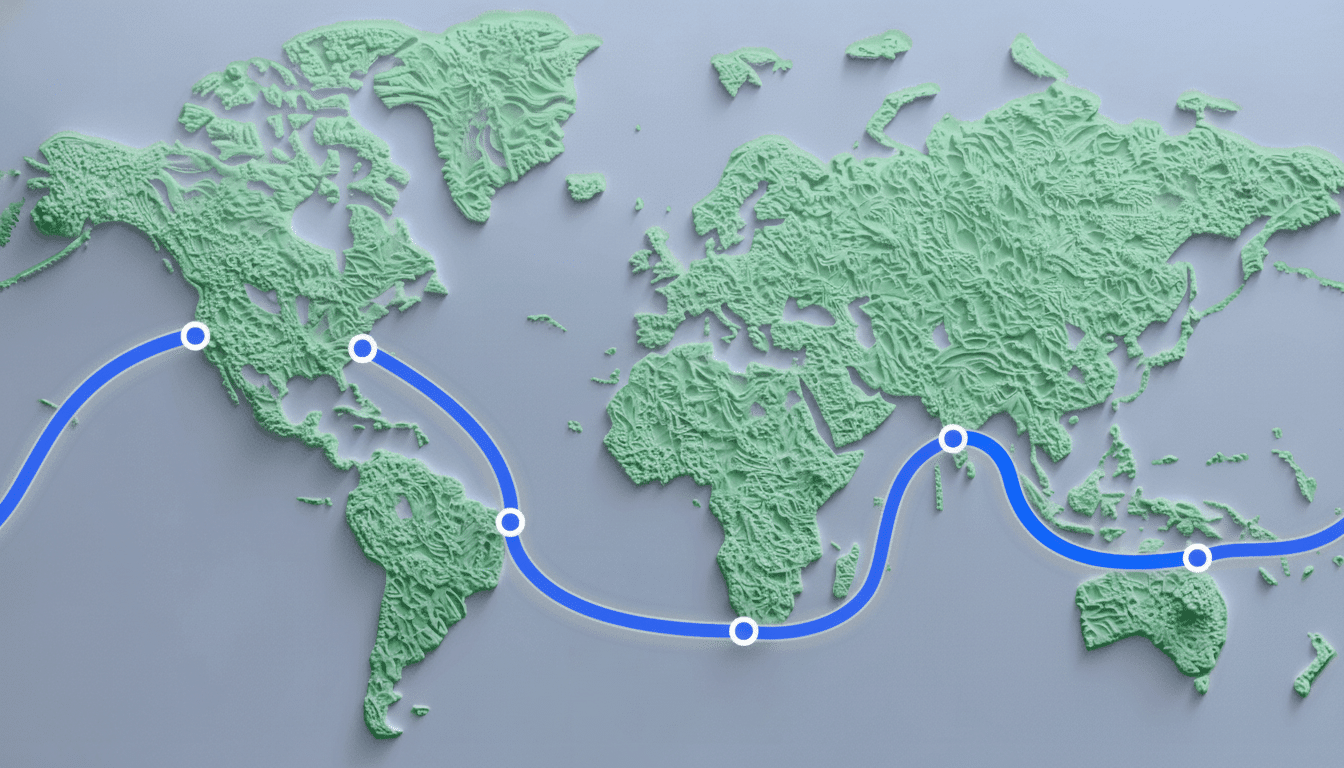

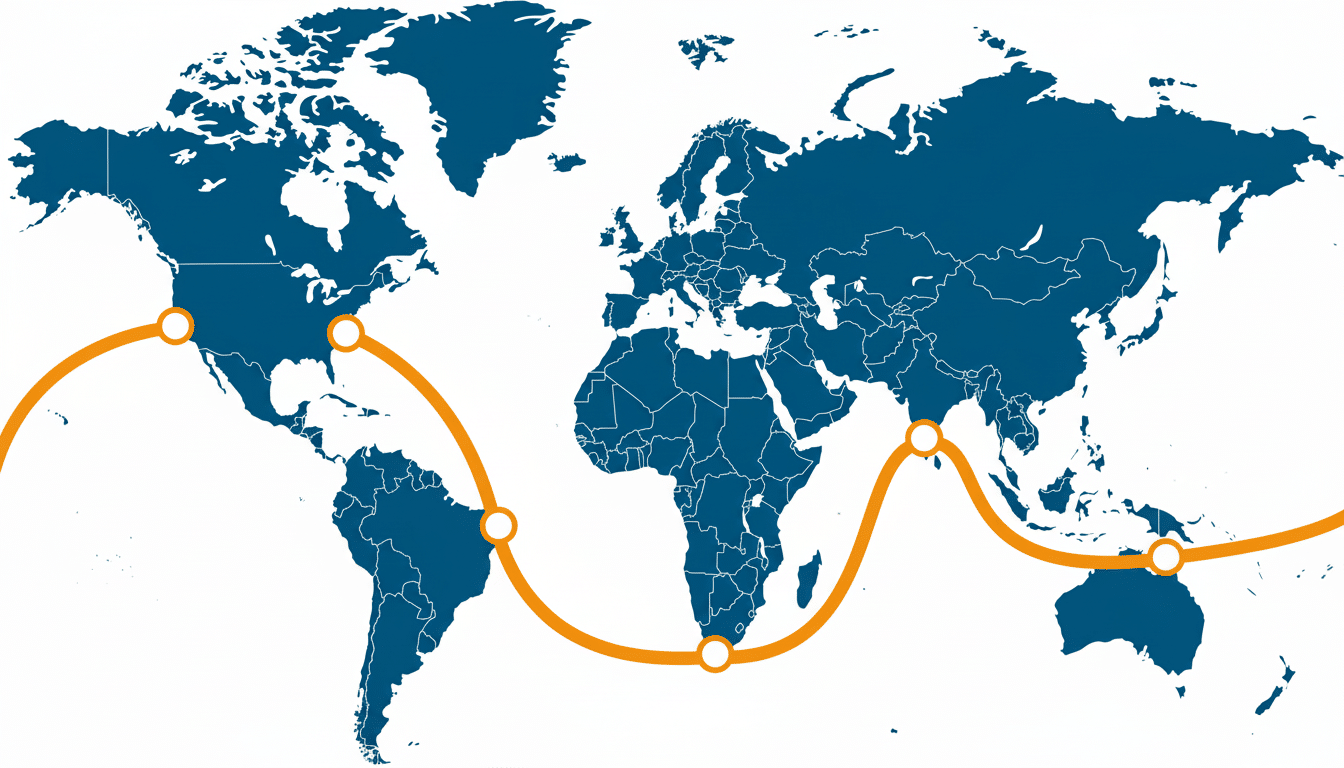

Project Waterworth is designed to be the longest single-run subsea cable system, the company said in disclosures. The system will loop between the United States, Africa and India, down toward the northern Australian coast and across to the Pacific—an architecture that blends familiar shipping corridors with new backwaters in order to increase resiliency.

Submarine cables actually service approximately 95–99% of intercontinental internet capacity, a statistic many overlook until something goes wrong. Industry tracking by TeleGeography demonstrates that hyperscalers now account for the majority of new capacity—and Waterworth is designed with that reality in mind. Look forward to spatial division multiplexing (SDM) with many fiber pairs, coherent optics, and C+L-band amplification—a strategy that spreads power among more fibers and opens up orders of magnitude more spectrum per wet plant than previous generations.

How engineers survey a planet-scale subsea route

The project is transitioning from “desktop study” to the part where work on the water gets difficult: mapping seafloor conditions at scale. In shallow or otherwise confined waters, other boats and autonomous platforms take over. The team scours the bottom for things that might require a detour—shipwrecks, pipelines pinged by magnetometers, abrupt escarpments, or submarine canyons where the fiber could be hung like a tightrope.

Engineers want the cable to sit on the ocean floor, which can be trenched, and buried where feasible. Slopes have to be no more than around 10–15 degrees for a sea plow to form an adequate trench. Crews also collect cone penetrometer samples to estimate seabed density and burial feasibility; that protective layer in shallow water is what allows cables to survive fishing gear, anchors, and shifts in the sediment. From end to end, surveys and permits can take months to years—not bad when you’re measuring the contours of a planet’s worth via hundreds of miles of cable.

The hazard model factors in both nature and people. Volcanic activity and earthquakes have cut island links within living memory, while a single high-profile cut between the tectonic plates of the Red Sea at regular intervals disrupts around 25% of regional traffic. The step-over slip episodes help explain why Waterworth emphasizes route diversity and choke-point avoidance. In subsea, it’s not a matter of fancy; redundancy is the only feasible operational position.

The route for Waterworth and the strategic reasoning

The US–Africa–India section redoubles a well-trodden rejuvenation in capacity with markets where the demand for cloud and mobile services continues to increase. South from India, the line veers back toward northern Australia as it plows across the Pacific along an unconventional path. A great deal of Asia–US traffic historically moves from Singapore through the South China Sea to Japan, where it hooks left and crosses the North Pacific. Waterworth’s alternative geometry disperses geopolitical and geophysical risk, diversifying the points of landing.

Landing is as strategic a decision as the deep-water route. Landings rely on local permitting, power access, backhaul into terrestrial networks, and environmental assessments. Standards set by the International Telecommunication Union help keep equipment interoperable, but every shore touch still requires country-by-country approvals and coordination with coastal authorities and marine users.

The Timeline Is Being Driven by Demand for AI

The engineering behind the move is straightforward: AI and data-heavy services saturate present backbones. Training and inference workloads drag in gigantic datasets between regions, and hyperscale data centers need deterministic low-latency paths to operate. In the words of one subsea veteran, data centers isolated from connectivity are simply big sheds. According to TeleGeography’s analysis, demand for international bandwidth has been compounding at a double-digit pace with cloud providers in the vanguard.

Waterworth will plug into Meta’s global network fabric, taking weight off clogged paths and making room to breathe through its inter-data-center flows. The company has not released a price tag, but projects of this length and complexity tend to be in the multibillion-dollar range, and take years from survey to service. Meta’s 2Africa build before that, which came after a long staging cycle, serves as a cautionary tale in patience: churning out miles upon miles of armored fiber and laying it down with precision hundreds of fathoms below the ocean surface takes time.

Why choosing boring seabed routes improves reliability

Paradoxically, the safest places to lay cables are actually some of the least ecologically interesting: ambient, stable patches that are primarily flat and aren’t biologically sensitive. That’s by design. There are occasional scientific discoveries down there—maybe the classic case of broken cables confirming the existence of turbidity currents—but cable guys tend to prefer dull. Boring routes create fewer surprises, lower maintenance costs, and better network uptime for everyone who depends on the internet.

From here, the builder undertakes detailed surveying, finalizes the alignment, and moves into manufacturing and laying, in advance of handover. When activated, the system will route general internet traffic as well as Meta’s internal workloads, bringing both capacity and diversity to the global mesh. For users, the effect should be imperceptible—which, in the realm of subsea cables, is precisely the goal.

Sources: Company disclosures and interviews; TeleGeography industry data; International Cable Protection Committee guidance; independent news outlets on Red Sea outages and hyperscaler cable investments.