Max Hodak helped make brain implants a conversation we have with our tech at Neuralink. Now, with Science Corp., he’s aiming the field somewhere even weirder and more ambitious: a path that begins with sight restoration, travels through gene therapy and ends in biohybrid neural tissue meant to fuse seamlessly with the brain.

From Retina Chips to Revenue: Science Corp.’s Strategy

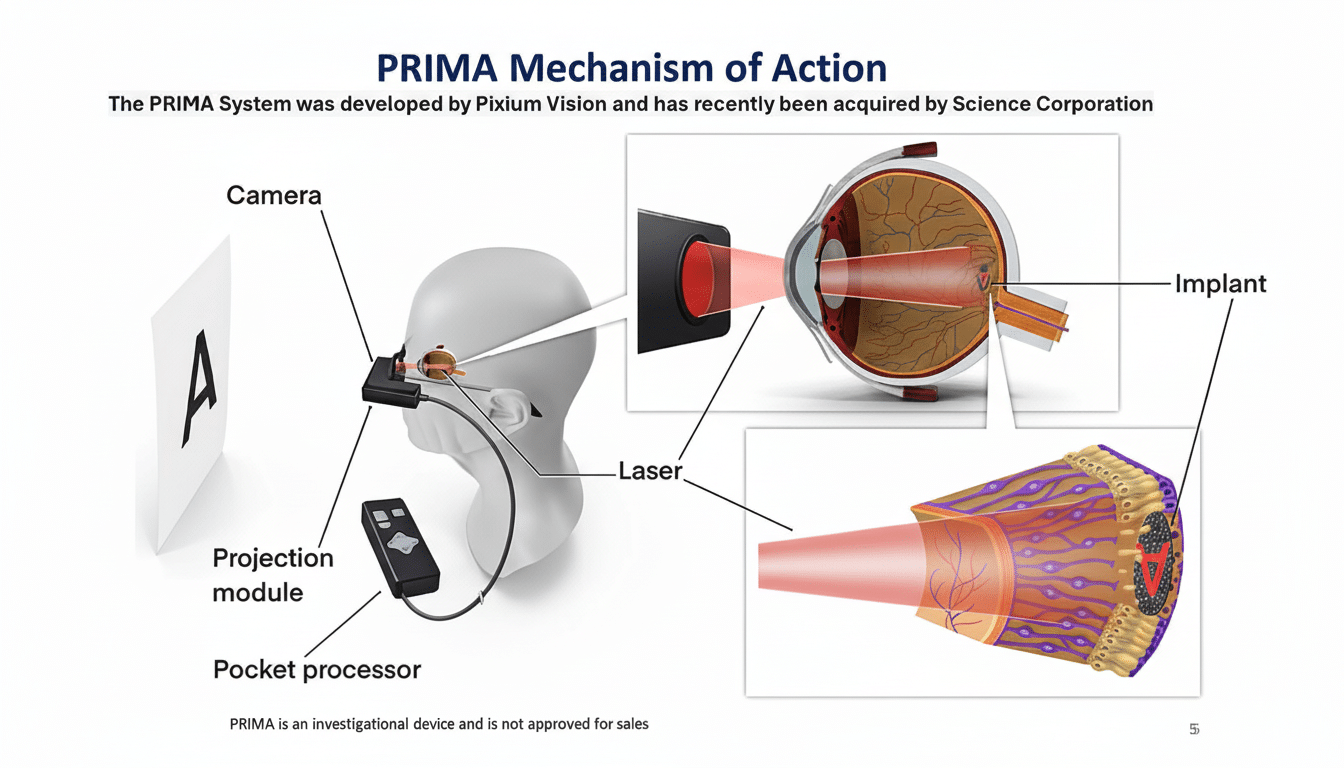

The company’s initial wedge is pragmatic and commercial: a retinal implant named Prima. The technique combines a less than a grain-of-rice-sized chip in the back of the eye with camera-equipped glasses and an external power source that together provide “form vision” for people who are almost completely blind due to advanced macular degeneration. The work pulled a recent magazine cover, not for hype but because of the results.

- From Retina Chips to Revenue: Science Corp.’s Strategy

- Why the BCI Race Is Speeding Up Across Tech and Policy

- Beyond Electrodes: A Gene Therapy Bridge for Vision

- The Biohybrid Leap: Grow Neurons, Not Wires

- Consciousness as the Endgame Beyond Cognition Alone

- The Cost Curve and the Policy Gap for Neurotech

In preliminary studies with 38 participants, Science Corp. says, 80 percent could read again — even though just a few words at a time — after years of unusable central vision. The company licensed the technology from Pixium Vision, modified their techniques and firmware — software embedded in hardware — and presented data to European regulators. In the U.S., it’s in ongoing conversation with the FDA.

Prima is special for another reason: it’s a go-to-market plan in a space known for moonshots. Hodak estimates that the first few procedures cost around $200,000. With roughly 50 patients a month, he says Science Corp. could be sustainably profitable while providing funding for riskier, longer-horizon bets.

Why the BCI Race Is Speeding Up Across Tech and Policy

Brain-computer interfaces are increasingly mainstream. The World Economic Forum has counted nearly 700 organizations with some kind of interest in BCI. Giant tech players are in the race: Microsoft Research has for years investigated noninvasive BCI paradigms; Apple has teamed up with Synchron to allow implants to control iPhones and iPads; and Chinese regulators have published a national roadmap to take the industry from prototypes to strategic capability.

Hodak’s perspective reflects a growing consensus: the fundamental neuroscience of interpreting intent is not new. The breakthrough is engineering: creating relatively tiny, low-power, biocompatible devices that can be fully implanted so they sit just under the skin with no risk of chronic infection. That kind of transition frees up real-world dependability instead of being lab-only demos.

Beyond Electrodes: A Gene Therapy Bridge for Vision

Science Corp.’s next foray: optogenetic gene therapy for vision. Rather than depending on microelectrodes to excite bipolar cells of the retina, it plans to modify surviving cells so that they can simply respond directly to light through extremely sensitive and rapidly activating proteins. The eye is an appealing target because the structures in this organ enjoy a degree of immune privilege that diminishes the likelihood that bioengineered proteins will provoke harmful inflammation.

Rivals are working on similar ideas, but many of them target inferior layers in the cell or rely on proteins that can’t outpace sufficient darkness or match the sensitivity needed for naturalistic vision, says Hodak. If he’s correct, gene therapy may make hardware smaller and fidelity higher — a graceful connection between the implants of today and the biology-first interfaces of tomorrow.

The Biohybrid Leap: Grow Neurons, Not Wires

Electrodes hurt tissue and don’t scale well. That hard limit is why Science Corp. is experimenting with what it calls “biohybrid” interfaces: devices that sit on the brain like a little waffle, each pocket seeded with lab-grown, function-tuned neurons made from stem cells. The idea isn’t to prod the brain — it’s to mesh with it.

In early animal studies, the company says these neurons sent axons and dendrites into native tissue and impacted behavior. In one experiment, five of nine mice learned to turn left or right as the device switched on. A built-in safety feature serves as a kill switch: if necessary, a patient would take an ordinary vitamin that sweeps away the genetically engineered cells.

So the idea was out-there radical but also very simple: Neurons talking to neurons should more seamlessly integrate than metal talking to neurons. If scalable, that could increase the number of “channels” far beyond what silicon electrodes can safely reach.

Consciousness as the Endgame Beyond Cognition Alone

Hodak casts the mission as being “longevity-adjacent,” but the horizon line is more consciousness than cognition. While intelligence can run on any number of different substrates, consciousness is the tougher nut to crack. Solve the binding problem — how billions of neurons work together to create a unified, subjective experience — and devices may be able to not just treat disease but network our minds, extend ourselves and redefine what qualifies as a person.

He outlines a cautious path to adoption: begin with patients who have no good options; make surgeries safer; and let the benefits compound. Over time, use cases broaden. The far end is provocative — alternatives where someone, confronting a terminal diagnosis, continues to exist in biohybrid systems rather than allowing the biological body to fail.

The Cost Curve and the Policy Gap for Neurotech

There’s a looming economic tension. Consumer tech deflates — better, cheaper, faster. Healthcare is on a budget. If BCIs truly expand “healthy” life, or improve capability, demand will skyrocket; but payers cannot spend 10× as much without breaking. Today, insurers cover treatments for macular degeneration; cognitive enhancements tomorrow might compel queasy triage around who gets access.

Policymakers, regulators and payers will need standards for safety, equity and reimbursement before it’s a case of the tech outrunning the rules. That begins with therapies like Prima, which are legible, measurable and reimbursable — and that could bankroll the research required to make biohybrid interfaces real.

Hodak’s wager is that the quickest route to the weird future lies in pragmatic victories today. Restore sight now. Replace electrodes with light next. Then, grow neurons. If he’s correct, the locus of power in neurotechnology will move from decoding brains to building with them.