There was horrified disbelief after French newspaper Libération reported that the password to the Louvre’s video surveillance system was “Louvre.” The revelation comes after a high-profile robbery in which burglars walked away with crown jewels worth an estimated $102 million, and has prompted the world’s most visited museum to take a closer look at digital hygiene.

At the most basic level, having a single, guessable word protecting something so sensitive is a monumental screw-up. Even if you had other forms of mitigating controls, a password that is the same as the organisation allows for brute-force attacks, insider threats and social engineering. And for an institution that manages more than half a million works, the risk extends beyond one gallery: surveillance systems are often linked with access control, alarms and incident response workflows.

How One Word Became a Single Point of Failure

Over the years, security teams may be working with inherited legacy configs that have “temporary” credentials floating around or vendors ship systems with defaults that are never changed. Video management platforms in particular can get missed—thought of as facilities equipment rather than IT parts, and thus ignored when it comes to centralised password policies or monitoring or multi-factor authentication.

That blurring of responsibility is dangerous. CCTV consoles might contain camera maps, floor plans, or admin tools that could be abused to blind cameras, loop feeds, or time an intrusion. While in this instance the attackers may not have used it, such a backdoor would complicate forensics and risk eroding public trust.

A Familiar Weakness, With New Data to Consider

Weak, recycled passwords continue to be a top compromise vector in virtually all industries. And in its many iterations, the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report has consistently identified people as the vulnerability that’s central to most breaches, such as stolen or weak credentials being one of the top attack vectors year after year. It’s not just “123456” and “password”—any word associated with brand names, places or team mascots can be especially popular among hackers looking to break your password because attackers build dictionaries based on this public information.

NordPass has been publishing an annual list of the top passwords which, with virtual certainty, are predictable little strings that can be cracked in a heartbeat. There are tens of millions of accounts worldwide using “123456” as a password, according to the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre. The lesson is simple: if you can remember it — because the person who owns the building has a big name that you’ve heard of before — so can someone else.

Cultural Institutions Make Attractive Targets

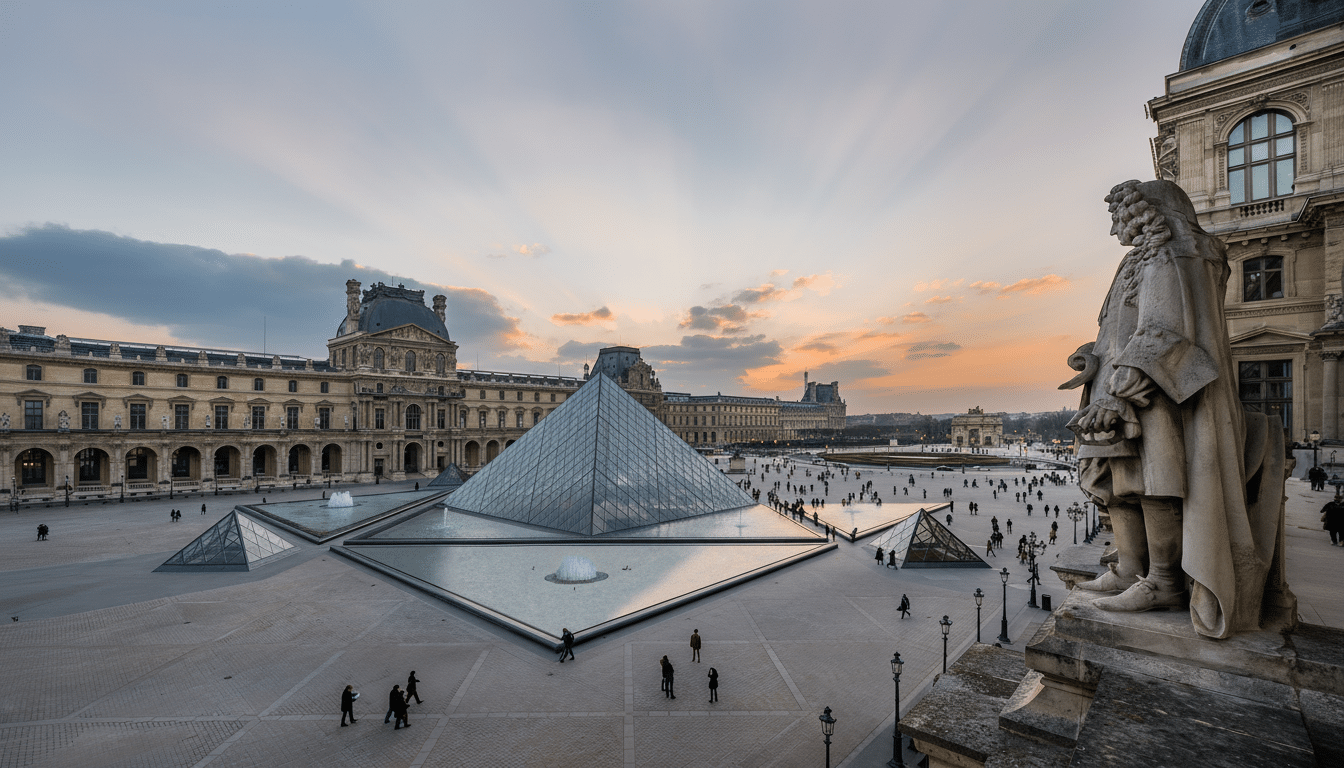

Museums and historic sites need to strike the right balance between openness and protection. Their brands and floor plans, as well as their exhibition calendars, are, by design, public knowledge — which provides criminals with ample information for reconnaissance. Valuable objects, small staffing windows and spiderweb-like contractor ecosystems make the threat model worse still.

History reveals how infrastructure shortfalls can magnify losses. The 2016 Mirai botnet wave mass-compromised devices using default camera and DVR credentials, evidence of the frequency with which operational tech lies undersecured. In the cultural sector, physical security and cyber controls need to be thought of as a unified system — because attackers will go after the seam where the two converge.

What Best Practice Is Now for Secure Operations

Modern guidance is unambiguous. (See NIST SP 800-63B and its advice to screen passwords against known-bad lists, ban context-specific terms that are easily guessable, like organisation names, and favour length over complexity gimmicks.) France’s ANSSI and the EU’s ENISA also recommend MFA for admin consoles, unique credentials per site, and regular rotation when there are role changes.

Even higher still for surveillance platforms and other operational technology: isolated networks, no internet exposure, only role-based access, tamper alerts, logging centralised with independent audit, emergency break-glass approach. Physical security keys, password managers and just-in-time access are now table stakes for systems that safeguard priceless collections.

Why This Matters Outside of Paris and Beyond

The Louvre’s prestige makes the story go viral, but the underlying problem is worldwide. City halls, hospitals, airports and galleries often find that convenience measures — one shared login, a memorable word — become liabilities years down the line. Insurance underwriters and regulators have become more aggressive in exploring these gaps, and claims relating to theft or business interruption can turn on whether “reasonably expected” controls were in place.

For institutions charged with protecting cultural heritage, the reputational damage can be as devastating as the actual theft. Donors, lenders and the public want to be assured that both the glass cases and the code behind the cameras are up to purpose.

What Comes Next for the Louvre and Its Security

Look for an internal review of vendor contracts, credential policies and network architecture — and a broader push for MFA and password blocklists on all operational systems. And regardless of whether the “Louvre” password played a role in the heist, the fix will be the same: Get rid of guessable credentials; eliminate single points of failure; ensure both physical and cyber teams are operating from a shared risk model.

Security, in the art world, is often gauged by what doesn’t happen. This episode is a glaring reminder that in 2025, a one-word password isn’t just quaint — it’s a vulnerability. Institutions everywhere would do well to take heed before a humbling detail becomes a costly headline of their own.