A Dutch startup called LeydenJar is touting a pure-silicon anode that, if it scales as promised, could chip away at China’s control of battery materials and rewiring the global economics of high‑density lithium‑ion cells. A new €13 million raise, combined with a €10 million commitment from a leading U.S. consumer electronics brand, indicates that first-tier buyers are prepared to validate the tech in commercial products.

Why silicon anodes matter today

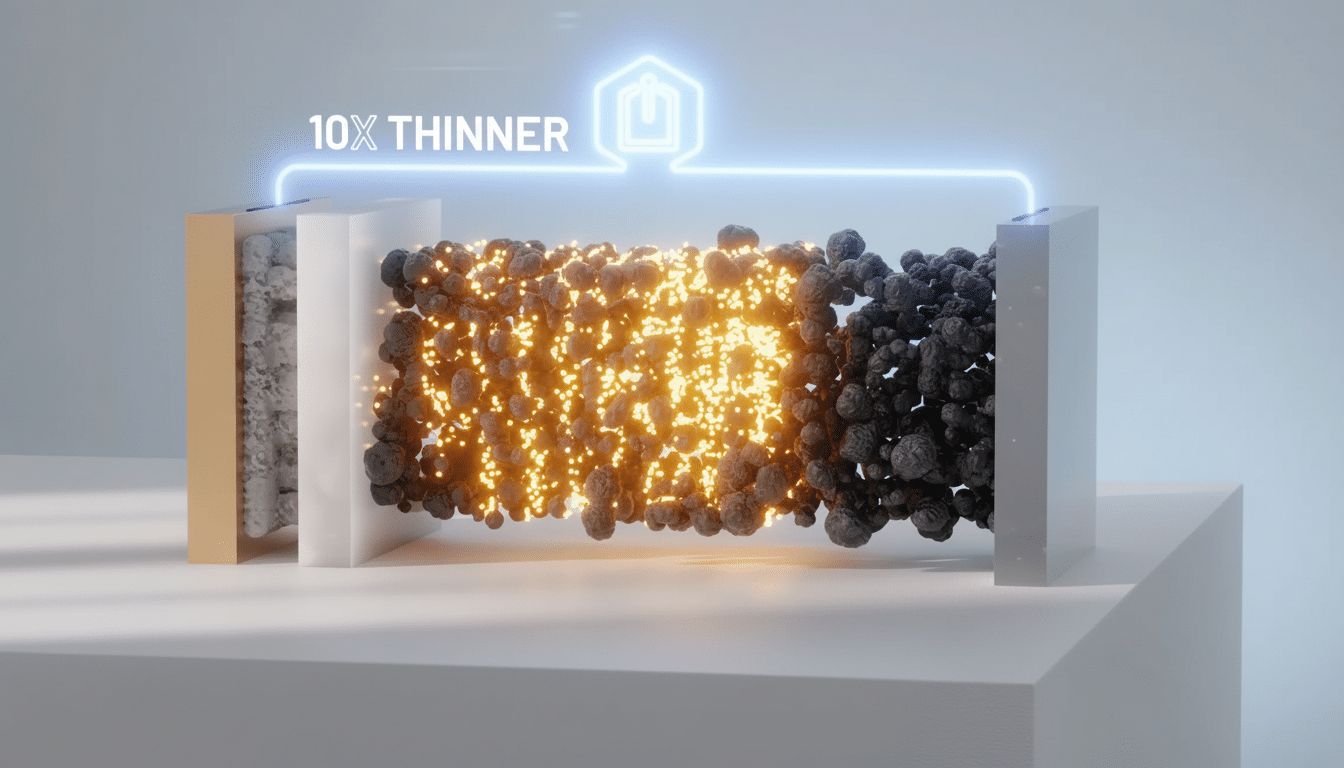

Intellectual Ventures Silicon can hold an order of magnitude more lithium than graphite, heralding step-up gains in energy density. LeydenJar claims that its silicon‑assertive anodes offer the potential to provide up to around 50% more energy compared to conventional graphite, leading to thinner phones, longer lasting wearables, and eventually lighter EV packs or more range without adding much cost or weight.

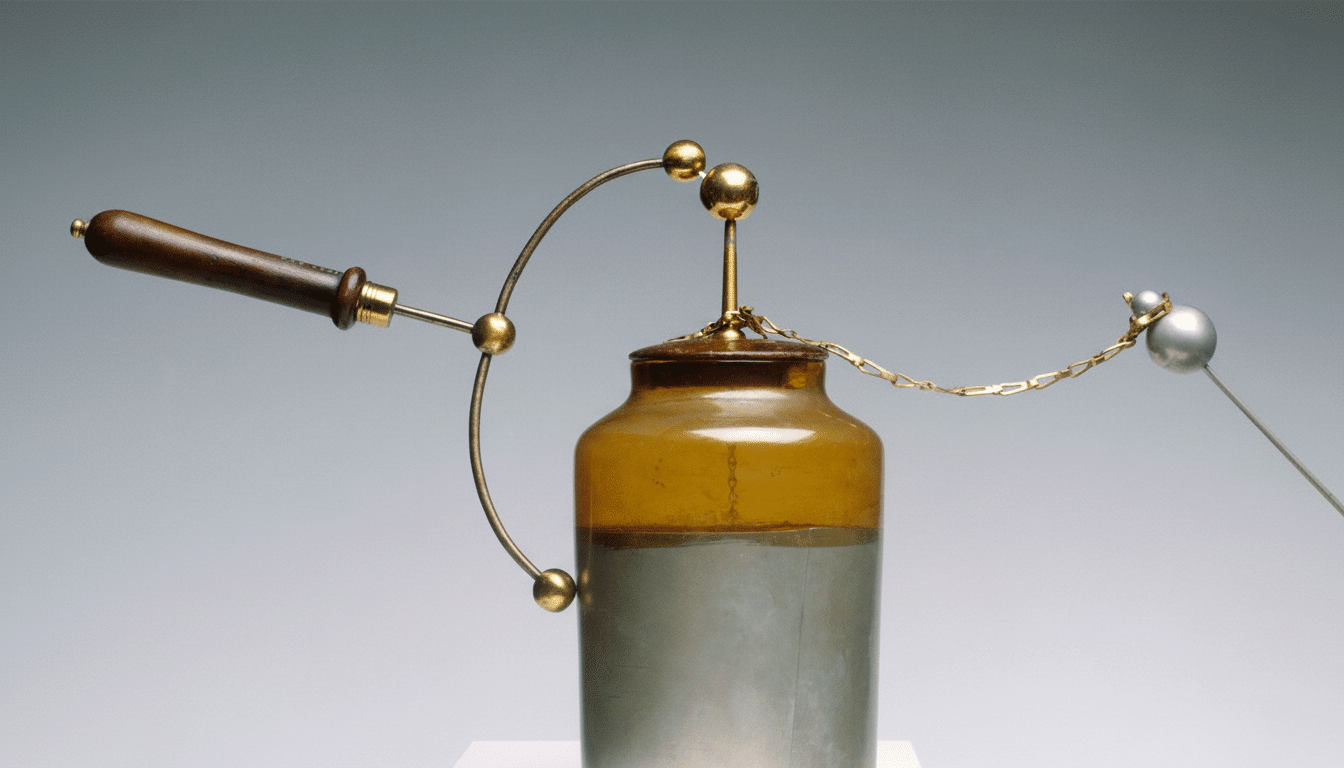

The catch has never been conceptual. Silicon expands while charging, causing typical electrode structures to disintegrate and slashing cycle life. LeydenJar’s method involves plasma-enhanced deposition to form sponge-like silicon columns directly onto copper foil. Room for swelling is provided for by the porous, vertical architecture which can aid in the retention of contact and conductivity during cycles.

Also aside from just capacity, the company is calling out faster charge performance and a lower lifecycle carbon footprint for the anode. That aligns with the EU Battery Regulation’s carbon disclosure requirements, which are ensuring suppliers measure and cut embedded emissions.

De-coupling from China’s grip on graphite

China owns the anode side of lithium‑ion. China produces and processes more than 90 percent of the world’s graphite anode and a substantial majority of its cell manufacturing capacity, according to the International Energy Agency and Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Export restrictions of certain graphite grades in recent years highlighted supply risk for Western OEMs.

Not only does replacing graphite with silicon-rich anodes provide a power boost; it also would alter supply chains. It further added that manufacturing high‑purity silicon structures in Europe will serve to lower dependence on Chinese processors and be in line with industrial policy objectives under the European Battery Alliance and the EU’s critical materials agenda.

From pilot to PlantOne: Scaling the test

‘LeydenJar to scale PlantOne using roll-to-roll plasma deposition in Eindhoven’ That process is capital intense, relative to slurry‑coated graphite electrode methods, so throughput, uptime and yield are the levers that will drive cost per kilowatt-hour. Investors Exantia and Invest‑NL headed up the latest round to finance the first phase, and the unnamed U.S. customer�€�s commitment provides demand visibility.

On durability, the company says it’s more than 450 full cycles before capacity falls below 80%. That’s fine for premium consumer electronics with refresh cycles on the order of a handful of years, but automotive buyers generally want something in the four-figure full-cycle equivalence to qualify. This preliminary lithiation will be another crucial integration ridge with cell partners because it balances the initial silicon loss.

The go-to-market path mirrors rivals. Sila brought silicon‑based anodes to wearables before pursuing the automotive market. The disadvantage so far has been the expense, but several of these firms are also developing more affordable versions Group14 is commercializing silicon‑carbon composites to reduce mechanical stress, and Amprius uses silicon nanowires for aviation-grade energy density. LeydenJar’s differentiator is a silicon-dominant, binder‑free design that — if it stands up in mass production — could pack in more energy than composite approaches.

Why OEMs are singing the call

Slog it out with consumer brands who seek every millimeter and milliamp-hour. Between a 20 to 50% energy bump at similar voltage is the sort of gain that means thinner devices without sacrificing battery life or, conversely, the same form factor but a meaningfully longer runtime. The extra fast-charge acceptance is a plus for the user and an overall grid-friendly power control.

For cell makers, LeydenJar claims its electrode can be dropped into existing lines without too much interruption. The one exception is that the silicon anode itself is deposited; downstream calendaring and assembly is all the same. If independent labs and OEM validation are in place and process compatibility and yields are stable, adoption friction falls off a cliff.

A strategic wedge against China’s advantage

Policy tailwinds matter. New U.S. rules set under the Inflation Reduction Act on “foreign entity of concern” content also make non‑Chinese anode supply particularly valuable for incentive eligibility. In Europe, plans for self-reliance in local battery materials, recycling and clean power further tip the scales towards domestic, low-embedded emissions anode making.

China’s champions won’t stand still. CATL, BTR, Shanshan, et al., are promoting silicon‑rich anodes and have unbeatable equipment and precursor supplyscale advantages. That paves the way for a race: If LeydenJar can reach automotive-class cycle life, demonstrate fast-charge reliability and actually reduce cost per kWh at scale, it could provide the foundation of an anode Europeans can trust is a credible alternative to China’s.

What to watch next

Some of the key achievements are validation of third party for cycle life of more than 800 full cycles, 10% – 15% reduction in fast‑charge time demonstrated at system level and stable line yields above 90% in sustained runs. Track the cost per kWh against premium graphite, lifecycle CO₂ disclosures under EU rules and announced tier-one partnerships with cell makers.

If those boxes are checked, LeydenJar won’t just bring slimmer devices to life—it will create a scalable blueprint for breaking the world’s most China‑dependent battery bottleneck.