Security researchers say a newly discovered Android spyware campaign has garnered some 100,000 victims in more than 196 countries. Telecom equipment was used to create software targeting Samsung Galaxy phones and to tauntingly place photos of Russian President Vladimir V. Putin on infected devices to show the true origins of malware that lasts anywhere from seven hours to 15 days, depending on how quickly its authors choose to uninstall it.

How the Exploit Chain Functioned on Samsung Galaxy Devices

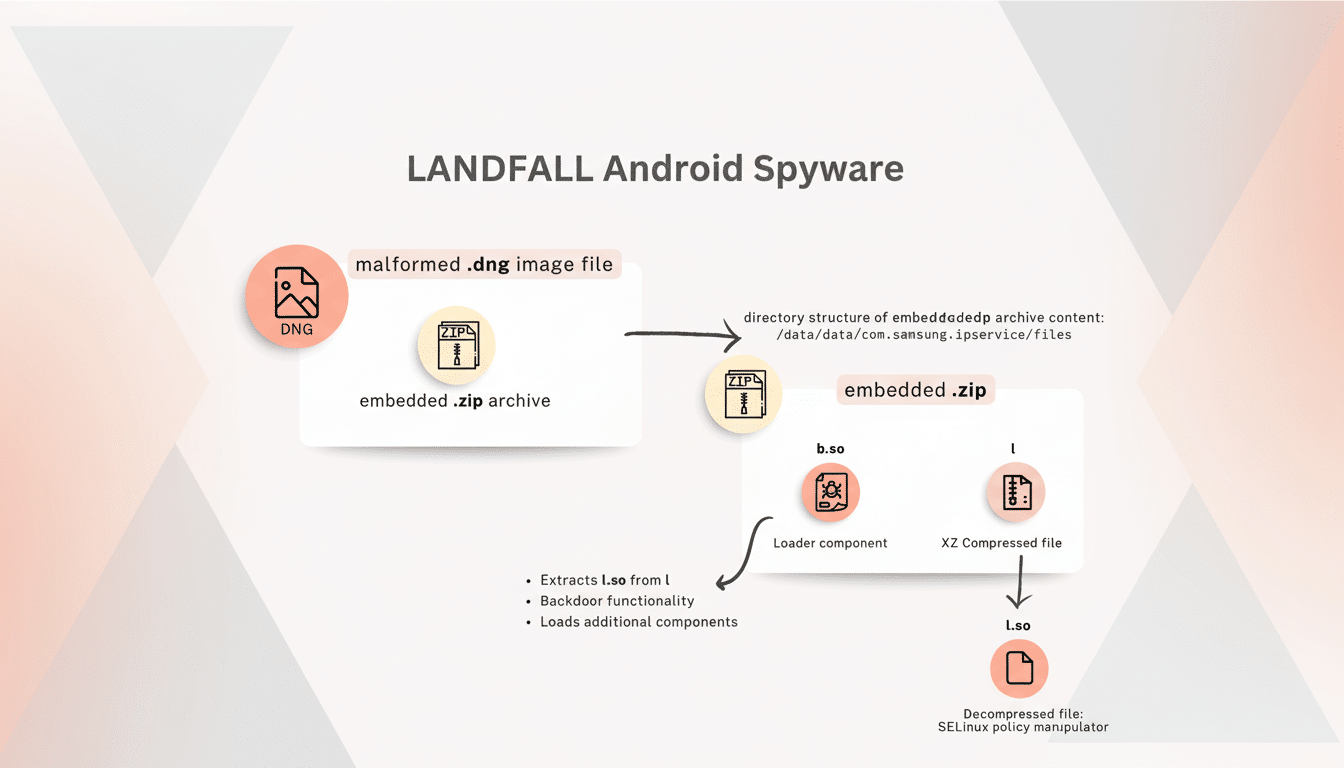

Landfall “took advantage of a zero-day in Samsung’s code that allows handset owners to gain full read and write access to any developer device on startup by simply flashing an image from their custom skin which is specifically tuned for developer purposes,” wrote investigators at Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42.

The booby-trapped file was apparently delivered via “a particular messaging application,” and in some instances may not have needed the victim to tap on anything for the hijack to work.

It wasn’t known to Samsung when the attacks started, in about July 2024, but was subsequently catalogued under CVE-2025-21042. Samsung addressed the issue in an April 2025 security update, but the broader strokes of the campaign had not been publicly detailed until now.

Unit 42’s analysis suggests the exploit chain impacted Galaxy devices running versions of Android from 13 through 15. Code references within Landfall samples name-checked several Samsung models, such as the Galaxy S22, S23 and S24, as well as multiple variants of its Galaxy Z foldable range—indicating custom testing against high-volume flagships.

Targets and geographic clues behind the Landfall spyware campaign

Attribution remains incomplete, but the telemetry is revealing. Landfall samples were first submitted to VirusTotal in 2024 and early 2025 by users from Morocco, Iran, Iraq, and Turkey, according to Unit 42. Turkey’s purpose-built cyber readiness center, USOM, has also independently categorized one command-and-control IP associated with Landfall as malicious, indicating an aspect of regional targeting.

It’s unclear how many users have been targeted, and researchers have not determined the spyware’s creator. Unit 42 said activity and infrastructure overlap with systems previously tied to surveillance body, the group of hackers known as Stealth Falcon, which independent researchers have connected to operations against journalists and dissidents in the Gulf region spanning years. It’s a remarkable series of overlaps, but inconclusive; who the government customer might be has not been credibly identified.

What Landfall Could Access on Compromised Galaxy Devices

Landfall feels like the product of modern mercenary spyware. Once established, it can rifle through core device information like photos, messages, contacts, and call logs. The tooling includes live surveillance capabilities (e.g., microphone activation, precise geolocation) and communicates with its remote server for command-and-control operations, to fetch instructions or exfiltrate files.

Although many consumer security products would be able to identify the known malware families, zero-day delivery penetration and post-exploitation stealth will allow these implants to run for years. In previous cases, other toolkits like this one have been used to throttle network usage, remove artefacts, and then adapt themselves to patch cycles in order to maintain access. Landfall’s activity seems aligned with those tradecraft patterns.

Patch Status and Exposure for CVE-2025-21042 on Galaxy

A patch for CVE-2025-21042 was provided by Samsung within its April 2025 security maintenance release. Devices that installed that update—or any of the subsequent monthly updates—would be protected from the exploit path known at the time. The company did not respond to questions about how widespread the vulnerability was, how quickly it is patching affected devices, or when the patches are being distributed.

The calculus of risk is severe because Samsung is still the world’s No. 1 maker of smartphones by shipment, commanding as much as 20% of the global market. For an espionage adversary, a proven zero-day across two generations of Galaxy makes for a high-reward vector, even if the campaign were only aimed at specific users and not rampant consumer compromise.

Why This Case Matters for Mobile Zero-Day Spyware Risks

Landfall fits into a growing canon of mercenary spyware incidents that have relied on mobile zero-days, and a market that has faced ongoing criticism from civil society and regulators. Organizations including Citizen Lab and Amnesty International have documented cross-border surveillance operations using the same techniques time and again, as US and EU officials rush to blacklist or sanction certain vendors. These steps aside, the economics of private-sector offensive security still encourages the discovery and weaponization of mobile insecurities.

The defenders learn the same old lesson, but more urgently: shrink those patch windows, harden those default messaging behaviors, and invest in anomaly detection that’s been tuned to the mobile threat landscape.

Practical steps for at-risk users include:

- Ensure the latest Android security updates are installed.

- Switch off automatic media download in messaging apps where available.

- Closely inspect app permissions.

None of them is a silver bullet against a zero-day, but all together reduce the attack surface.

Unit 42’s discovery is another data point in a larger trend: high-end mobile surveillance is now not the exception, it’s the operation. Lives and sensitive information can be most vulnerable in the window from discovery to patch deployment. Filling that gap is the industry’s most urgent problem.