Kevin Rose has a provocative new filter for backing AI hardware: if a wearable is so repugnant you want to punch the person for wearing it, then it’s a nonstarter.

The investor’s point isn’t about the violence; it’s a stress test for social acceptability, the frequently ignored limitation that has killed more futuristic gadgets than battery life or bandwidth.

Rose, a general partner at True Ventures and an early investor in Peloton, Ring, and Fitbit, notes that AI wearables live or die based on whether they adhere to human norms. Video recording without clear consent, microphones that are still active, and wearable designs all evoke instantaneous cultural isolation. A gadget must be more than just clever; it must be suitable for the kitchen, classroom, workspace, and date night.

Human–computer interaction has a term for it: social acceptability. Study after study, including research from Microsoft Research and academic HCI labs, finds that context and signaling—whether a device is recording or not, and how it looks—matter as much as the application. Rose’s heuristic of “would it make someone reach out and grab?” compresses this literature into one visceral checkpoint.

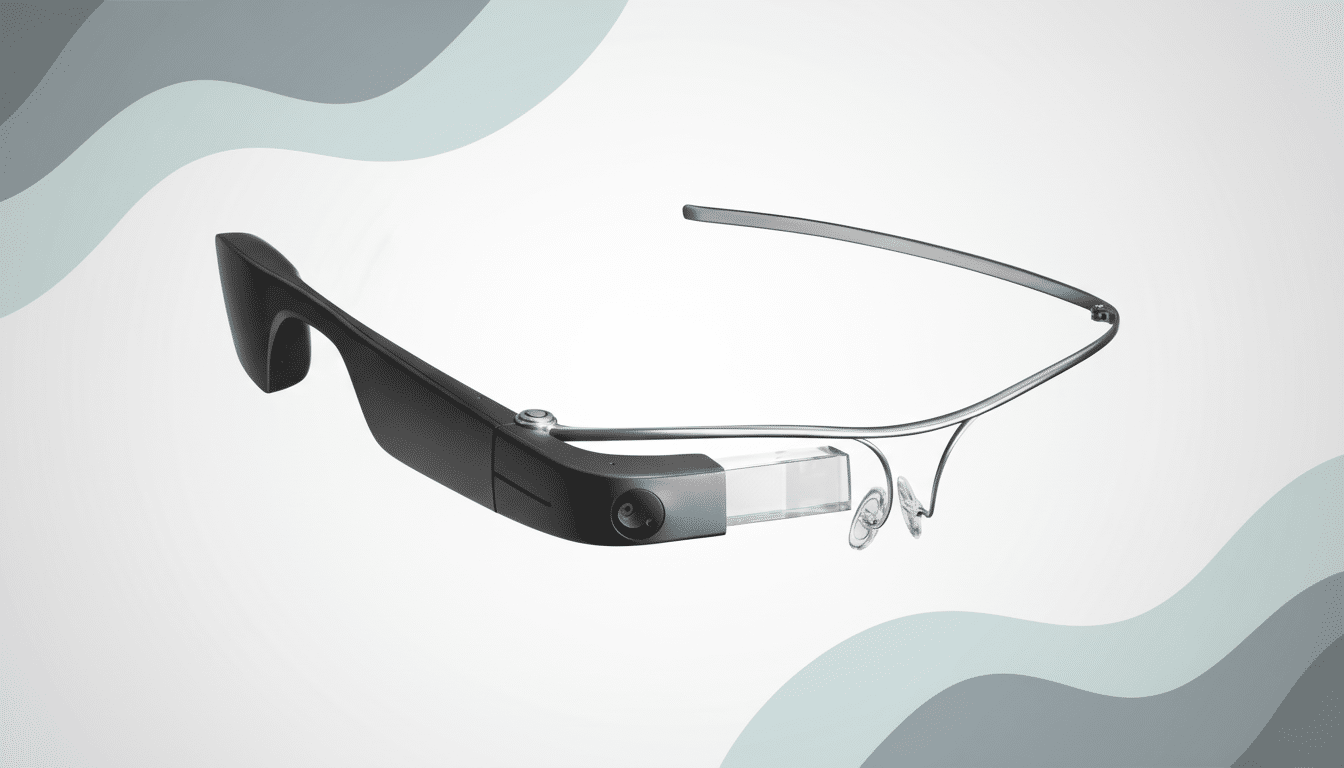

Lessons from Google Glass, Spectacles, and the Humane AI Pin

The cautions are stories we already grasp. Google Glass became “Glasshole” shorthand by putting a camera onto faces without adequate consent gestures. Snap Spectacles found a niche with clear recording lights yet never took off. Recently, the Humane AI Pin promised a screenless assistant but stumbled on battery life, latency, and that ambient feeling of surveillance; its rough debut included a recall of its charging accessory and a key rethink of the business.

Compare that with products that succeeded by seeming normal and useful. Rose also lauded Oura, where he served on the board, which focused on sleep and recovery with a discreet ring that wasn’t perceived as a camera or a mic. Market trackers estimate Oura captured about 80% of the smart ring sector, a sign that utility, style, and plain value can beat novelty for novelty’s sake.

Camera‑enabled devices can also win if they pass the vibe check. Rose noted Meta’s Ray‑Ban smart glasses look, well, like Ray‑Bans. The form is acceptable, and visible recording lights plus hands‑free tools for creators reduce friction. The directive to bystanders is clear: you can tell when they are on, and you can tell what they do.

Market data and norms that support the punch test

Wearables are a vast market, but not all categories benefit from the same winds. IDC and other analysts peg shipments in the hundreds of millions, with hearables and watches leading the way and camera‑equipped eyewear firmly in the minority. This is not a result of silicon limits but of consumer norms.

Pew Research Center has repeatedly found that large majorities of Americans feel they lack control over their personal information; devices that look like surreptitious recorders run right into that fear.

Regulation amplifies this. A patchwork of roughly a dozen U.S. states requires all parties to consent to audio recording, and many workplaces prohibit cameras on premises. That means your hardware’s default behaviors can put well‑meaning users squarely in legal gray areas. As a result, no one wants a product that generates HR emails or awkward “sorry, could you take that off?” in‑person encounters.

Design guidelines for AI wearables derived from Rose’s rule

Rose’s rule can be codified into product requirements.

- Obvious signaling: bright, unspoofable recording indicators and shutters that are default‑closed.

- Prefer on‑device processing with opt‑in syncing to the cloud to minimize data exhaust.

- Fast, intuitive controls for users and passersby—tap to mute, swipe to disable the cameras, a hard‑off state visible from across the room.

- Make that signal clear and rugged.

- Non‑creepy value: health metrics, accessibility benefits, and mission knowledge during activities score higher than indiscriminate life‑logging.

- Don’t bolt AI onto everything; features should solve a problem more effectively than the phone already in your purse.

- The tourist demo—“what am I looking at?”—is not a lasting reason to wear anything on your face.

Finally, design for relationships, not just individual users. If a device can escalate an argument by surfacing transcripts or logs, it’s creating more problems than it solves. Thinking in terms of households, classrooms, and teams leads to features like guest modes, auto‑redaction, and ephemerality that keep tech from becoming a third wheel.

What It Means for Investors and Founders

Rose’s investment filter is a call to discipline in an overheated cycle of AI hardware hype. The winners will treat social fit as a first‑class constraint, not an afterthought behind model size or parameter counts. They’ll ship devices that people want to be around, not just devices people want to demo.

For founders, this means testing in the wild—in cafés, schools, and subways—not just on lab benches. For investors, this means pushing teams to validate consent mechanics, public signaling, and failure modes as early as chip selection. Hardware that clears the punch test won’t merely avoid backlash; it will earn a place in daily life, which is the only adoption curve that matters.