If Pluribus made you quest for the true Kepler-22b, you’re not the only one.

The first known planet to orbit well within the habitable zone of a sun-like star has strutted back into the news, and with good reason: it’s one of NASA’s most tantalizing early achievements in the hunt for other worlds, and it stubbornly remains an enigma.

The Planet Beyond the Fiction: Kepler-22b’s real profile

Kepler-22b circles a G-type star a bit smaller and cooler than our sun, located about 640 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus. It travels around its star once every 290 days, which falls within the star’s habitable zone, where liquid water could in theory exist if the conditions were right.

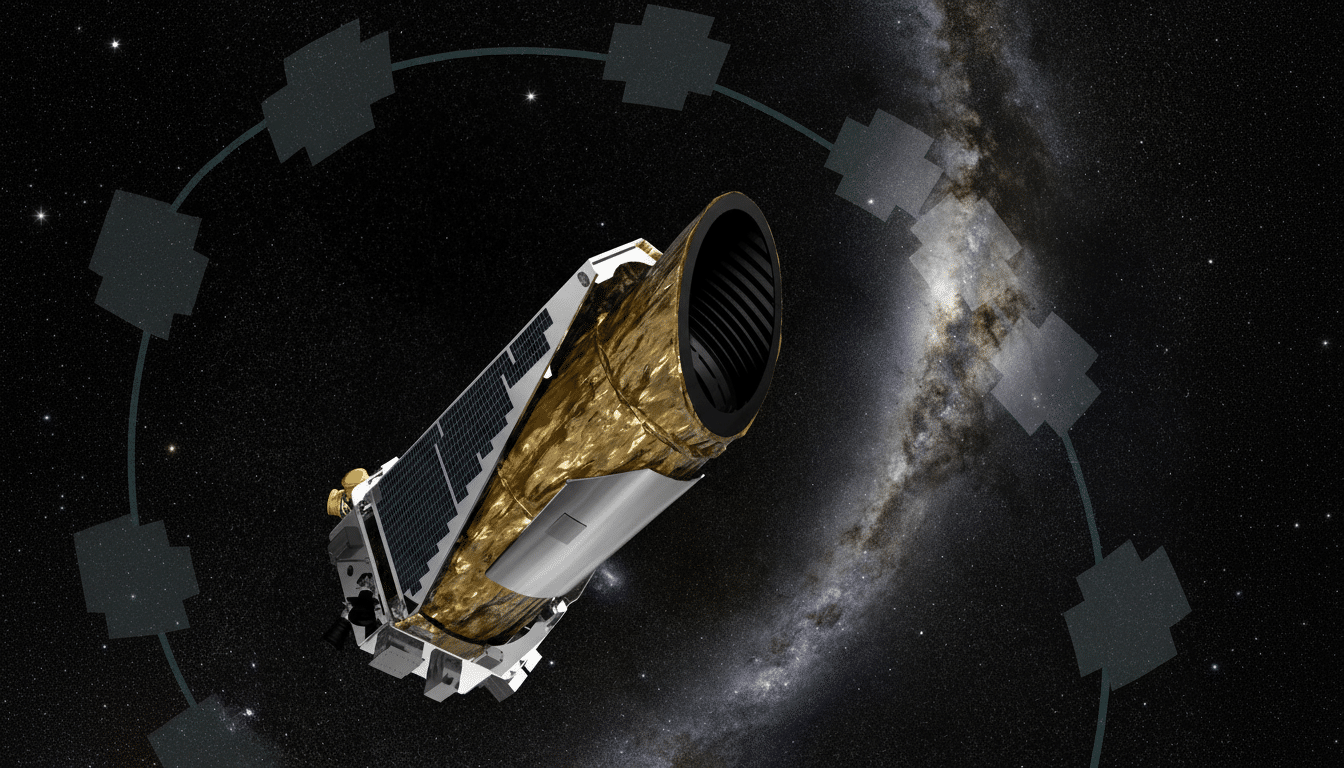

Identified in 2009 and confirmed in 2011 from data collected by the Kepler Space Telescope, the planet is about 2.4 times Earth’s radius — solidly a “super-Earth” in size, if not in actual makeup. In the absence of a measured mass, scientists don’t yet know whether it’s a rocky world, a deep global ocean planet, or something more like a mini-Neptune wrapped in hydrogen and helium.

How astronomers really found it using transit data

Kepler didn’t snap a photo. Rather, it waited for the small, periodic dimming of starlight as a planet passed in front of, or transited, its host star — a method known as the transit approach. The dimming is of only a few hundred parts per million for Kepler-22b, more like catching a cosmic blink. The three evenly spaced blinks were the clincher. “You know what William Borucki liked to say about that was, the first transit came a few days after the period in time when Kepler first became fully operational, and it was just an observational fluke,” Lissauer observed.

The likelihood of geometry being so kind was slim. In an Earthlike orbit around a sunlike star, there is approximately a 0.5% chance that the orbit lines up for transits as seen by us. Kepler found thousands of worlds because it stared at more than 150,000 stars at a time, an approach that revolutionized exoplanet science.

What we know about conditions on Kepler-22b so far

Early estimates had put the average temperature of Kepler-22b (if it were greenhouse-gas-free) within a comfortable 72° range, but that is a model-dependent placeholder. This can be estimated: a dense atmosphere (Venus, anyone?) would quickly turn the surface into a hellhole; a thin, Mars-like envelope could tenderize it with cold. The answer depends on the mass of the planet, its atmospheric composition, and clouds — none of which are nailed down.

Size offers clues. Using population studies of Kepler planets (including those published in The Astrophysical Journal), scientists have found that planets a little bigger than 1.6 Earth radii are less likely to be composed mainly of rock. Kepler-22b (at 2.4 R_E) may possess a significant volatile envelope or be mini-Neptune-like in nature. That doesn’t rule out habitability altogether, but it inclines expectations away from a twin of Earth.

Why it’s difficult to learn more about Kepler-22b

There are three practical reasons follow-up is difficult.

- The host star is dim to our telescopes — bright enough for Kepler’s exquisite photometry but not bright enough for good radial-velocity precision from the ground that would show mass.

- The planet’s orbital period is 290 days, so transits are few and far between, offering little time for atmospheric spectroscopy.

- At the anticipated star–planet separation of well below a milliarcsecond, direct imaging is beyond reach in current observatories, including the James Webb Space Telescope.

As for those radio beacons in the show: Teams at the SETI Institute and efforts like Breakthrough Listen have pored over many Kepler systems in search of narrowband signals. No compelling technosignatures have been observed in Kepler-22’s system thus far. The NASA Exoplanet Archive, however, has now tabulated over 5,500 confirmed exoplanets; Kepler, including its K2 mission, is credited with more than 2,700 — numbers that remind us of the distance we’ve come and how phenomenally far detailed characterization remains for most worlds.

A Milestone With Calculated Expectations

The significance of Kepler-22b is more historical and statistical. It demonstrated that Earth-sized or larger planets can exist in Earthlike orbits around sunlike stars — precisely the sort of configuration many hoped to find. But the “habitable zone” does not offer a guarantee of habitability. With no mass, atmospheric spectra, or direct reading of its surface, scientists must assume numerous ideas at once, from an ocean world to a gas-shrouded mini-Neptune.

For observers motivated by Pluribus, here is a ground truth: Kepler-22, the star, resides in Cygnus and takes at least a small telescope to pick up.

The planet itself is so faint that it’s out of range for most large backyard telescopes. And Kepler-22b is also 640 light-years away, and there is no possibility of visiting it (even if you traveled at the speed of Voyager 1, or about 38,000 mph, it would take roughly 11 million years to get there).

What comes next in the study of Kepler-22b and kin

The most promising way forward is patient, cumulative science: better radial-velocity campaigns with larger facilities to constrain mass, opportunistic transit spectroscopy with space observatories when the rare alignments do occur, and comparative insight from closer, brighter super-Earths discovered by TESS.

Flagship missions in the future designed to do direct imaging could eventually find planets like Kepler-22b — somehow, somewhere, out there.

For now, however, Kepler-22b remains on the fertile frontier that lies between imagination and evidence — a real exoplanet that has commanded attention, fueled storytellers’ dreams, and tethered a generation of searches to data-driven optimism about temperate worlds being not just plausible but ubiquitous.