The FBI is examining how Minneapolis anti-ICE organizers used the encrypted messaging app Signal, according to Kash Patel, who disclosed the probe during a conservative podcast interview. The move instantly drew bipartisan criticism and fresh constitutional questions about when digital organizing crosses the line from protected speech into criminal conduct.

FBI probe announcement made during conservative podcast

Patel said the inquiry was prompted by social media posts from self-described independent journalist Cam Higby, who claimed he infiltrated a Signal group that tracked alleged movements of immigration officers in Minneapolis, including license plates. Appearing on The Benny Show, Higby urged authorities to pursue a “witch hunt,” language that underscored the overtly political overtones of the episode. Patel, speaking immediately afterward, said the FBI would issue subpoenas, use grand juries, and “find out who broke the law,” framing the effort as a response to a public tip consistent with Bureau policy.

That origin story is unusual. FBI investigations are rarely rolled out on a broadcast, and even initial assessments typically proceed quietly under the Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide, which permits limited fact-finding without proof of wrongdoing. The on-air reveal raised concerns among legal scholars that political pressure, rather than evidence, may be driving investigative decisions.

Free Speech And The Line Between Monitoring And Crime

First Amendment experts note that watching public officials, sharing observations, and organizing protest activity are generally protected speech. Kevin Goldberg of the Freedom Forum told reporters that the posts attributed to the Minneapolis chat looked like activity “fully protected by the First Amendment,” with no clear incitement or obstruction. Under the Supreme Court’s Brandenburg standard, advocacy becomes unprotected only when it is directed to inciting imminent lawless action and likely to produce it.

Patrick G. Eddington of the Cato Institute called the effort “an epic constitutional and legal fail,” arguing that citizens may coordinate peaceful monitoring of government behavior, including potential abuse by immigration agents. Courts have repeatedly protected collective advocacy and boycotts, including in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, and have recognized the right to record officials in public in cases such as Glik v. Cunniffe and Fields v. City of Philadelphia. Any case against organizers would hinge on specific, provable conduct that crosses into threats, doxing intended to facilitate harm, or interference with operations—not the mere use of encryption.

What Investigators Can Actually Get From Signal

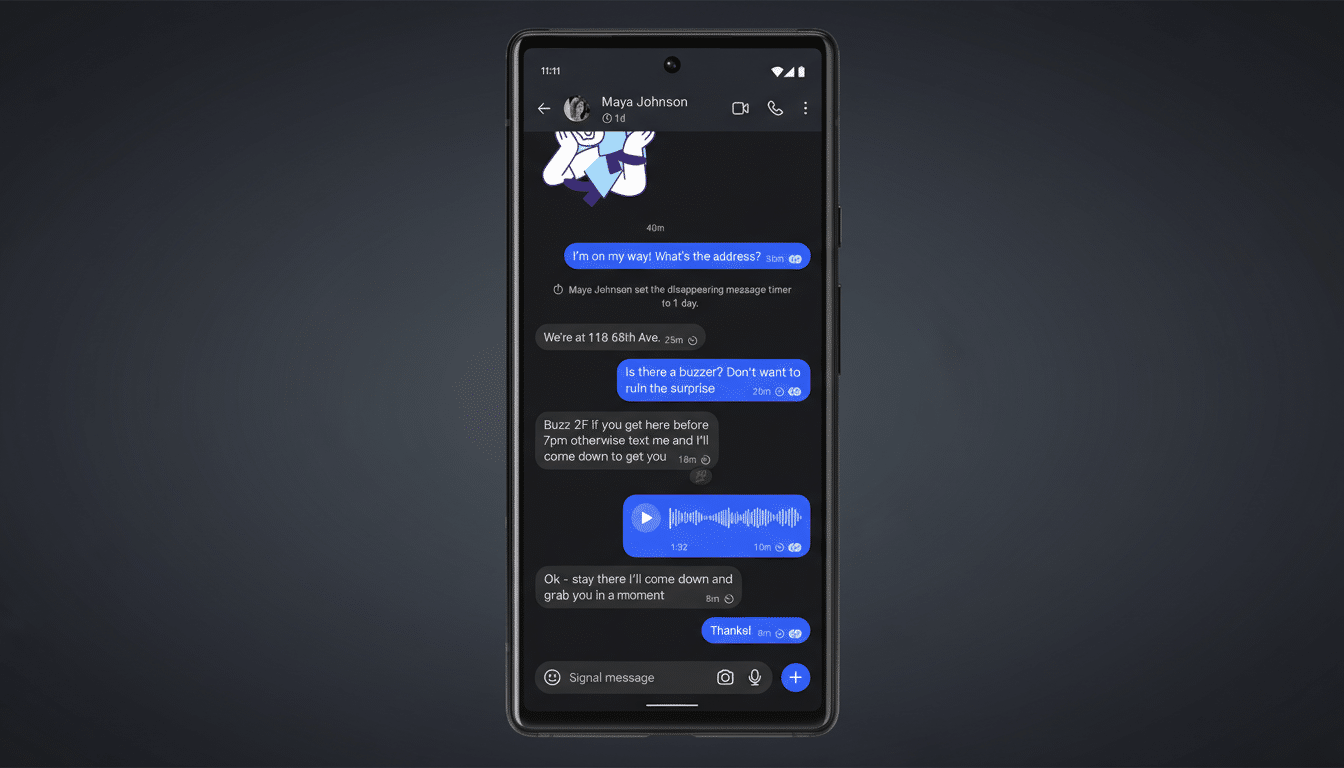

Signal uses end-to-end encryption, meaning the service cannot decrypt message content in transit or on its servers. In past legal matters, the company has said it can provide only minimal account data, such as the date an account was created and the date it last connected. That limits the value of server-side subpoenas for message content.

But that does not make chats untouchable. If authorities obtain a user’s unlocked phone—or crack it with forensic tools—messages stored on the device can be read. Public procurement records show immigration and homeland security agencies maintain contracts with forensic vendors like Cellebrite, a capability long documented by the Electronic Frontier Foundation. In short, the practical battleground is device access, not breaking Signal’s encryption.

Why Signal Is Central To Anti-ICE Organizing

Immigrant rights networks have relied on encrypted chats to alert communities to visible immigration enforcement activity, coordinate legal observers, and reduce risk to vulnerable residents. In Minneapolis and other cities, volunteers have cataloged locations, unmarked vehicles, and reported encounters to connect people to attorneys and hotlines. Supporters say these are classic civic watchdog functions; critics worry that sharing identifiers of officers could chill enforcement or escalate confrontations.

The legal terrain is nuanced. Public license plates and movements observed on open streets are generally not confidential, but posting personally identifying information with an intent to harass or threaten can trigger criminal liability under state or federal laws. That nuance is why process matters: an evidence-based inquiry focused on specific conduct differs sharply from an investigation premised on political rhetoric.

Potential Chilling Effects And What Comes Next

Announcing an FBI probe of a protest chat risks deterring lawful organizing, even if charges never materialize. Civil liberties groups like the ACLU have warned that broad surveillance or splashy investigations can chill participation, particularly among immigrants and mixed-status families wary of any contact with law enforcement. If the Bureau proceeds, watchdogs will look for adherence to predicate standards, narrow use of subpoenas, and internal review by the Justice Department’s oversight offices.

For organizers, the practical guidance remains familiar:

- Use strong device passcodes.

- Enable disappearing messages judiciously.

- Keep sensitive logs off phones.

- Separate public observation from any conduct that could be construed as interference or threats.

For the FBI, the test will be whether this case is built on demonstrable violations of law—or whether it becomes a high-profile example of how not to police encrypted political speech.