An administrative law judge in California has ruled that Tesla had misled customers with its marketing of what it calls Full Self-Driving and Autopilot capabilities, and must face sanctions, including refunding some customers who bought the feature within the last two years. The decision is a result of yearslong fighting with the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles, recommending 30-day suspensions of Tesla’s sales and manufacturing licenses. The DMV has halted those penalties and given Tesla 90 days to change its website to strip out any deceptive language, or if it does not, that is when the suspensions would kick in.

What the judge decided about Tesla’s Autopilot and FSD claims

The ruling, delivered through California’s Office of Administrative Hearings, revolves around the “net impression” of Tesla’s marketing. Regulators said that branding like “Autopilot” and “Full Self-Driving” generated the expectation of a high level of autonomy not met by systems that are classified as driver assistance (SAE Level 2) but require continual human monitoring. Tesla had argued that its statements were protected speech, but the judge ruled that the company’s advertising fell into the category of deceptive commercial claims subject to consumer protection standards.

- What the judge decided about Tesla’s Autopilot and FSD claims

- Why Autopilot marketing is under fire from regulators

- A high-stakes market test for Tesla in California sales

- Regulators Closing In On Multiple Fronts

- What compliance might look like under the DMV ruling

- More traffic for whom? Robotaxi pilots versus customer features

- The bottom line for Tesla after the California ruling

Although the DMV put the immediate suspensions on hold, the clock is ticking for what passes as adequate remediation. The agency has not offered a public standard or definition for compliance. In practice, the rule they say violated consumers’ rights is found in what regulators call “clear and conspicuous” disclosures that are as prominent as any claim, a standard often used by the Federal Trade Commission and mirrored in California’s false advertising laws.

Why Autopilot marketing is under fire from regulators

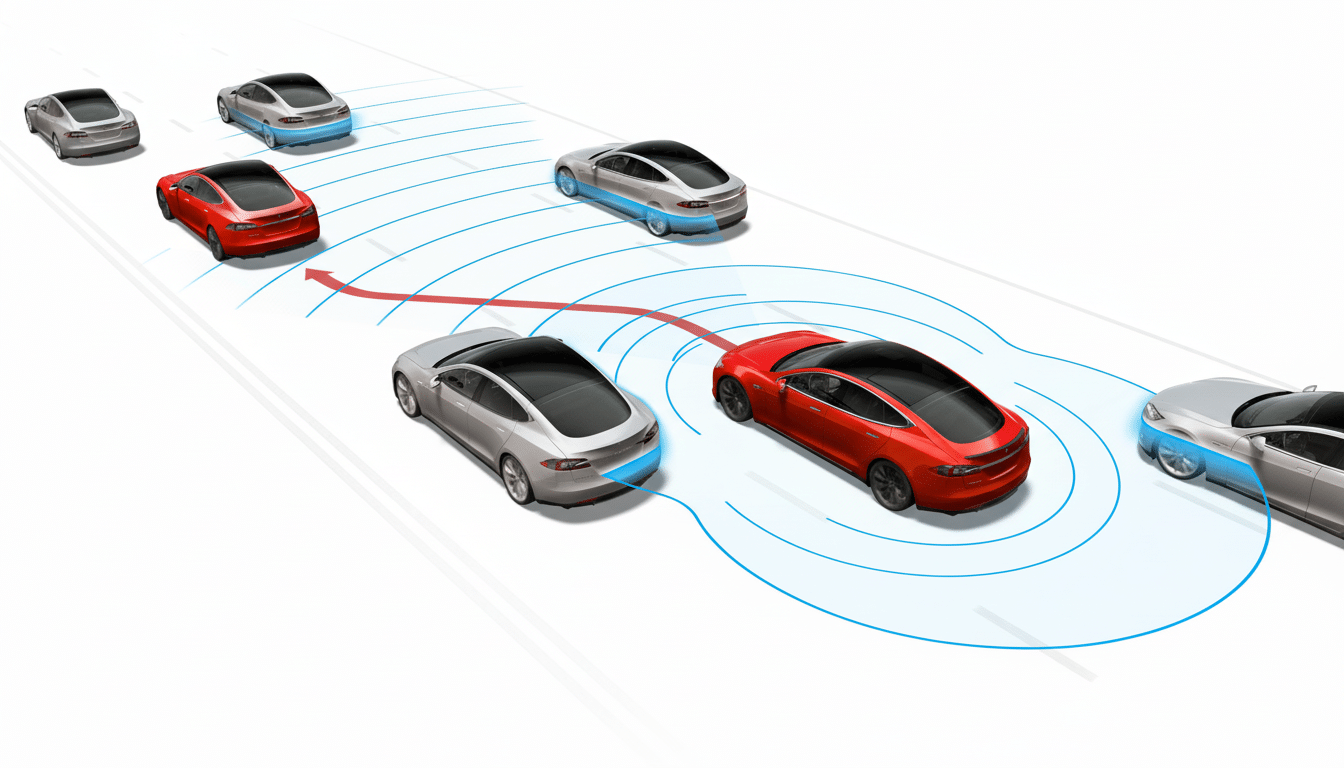

For years, terminology has been at the center of the debate. Level 2 systems, as defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers, are those that don’t handle driving entirely but help with steering and speed. Tesla’s own owner materials say drivers must keep hands on the wheel and eyes on the road, but critics argue that splashy claims and feature names obscure those warnings and foster overconfidence.

Safety regulators have documented the dangers of confusion. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration forced Tesla to expand the scope of an Autopilot recall in late 2023, when it mandated stricter driver engagement checks and warnings, and in 2024 opened a recall query to evaluate whether those changes were effective. NHTSA’s system for reporting crashes also has indicated that Tesla cars made up a high proportion of reported Level 2 driver-assistance incidents from mid-2021, which is consistent with their fleet size and the relatively high use of those features on public roads.

A high-stakes market test for Tesla in California sales

California has been a key market for Tesla in the United States: The Model Y and Model 3 have consistently ranked among the top-selling cars in the state in recent years, according to data from the California New Car Dealers Association. A mere 30-day sales suspension, at least temporarily, would echo through delivery lines and end-of-quarter targets. The temporary injunction to halt production has already been stalled, but as Tesla’s Fremont factory is a primary assembler in North America, including the Model 3, the judge’s recommendation certainly didn’t help.

Operationally, such a manufacturing pause could disrupt supplier schedules, rail and trucking logistics, and inventory planning many dozens of miles beyond the Bay Area. The business risk is not the loss of volume alone but what happens to margins if Tesla has to increase incentives elsewhere to make good on a California shortfall.

Regulators Closing In On Multiple Fronts

The DMV case is in keeping with wider scrutiny. The California attorney general, the Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission have all looked at Tesla’s assertions regarding driver-assistance performance and development schedules. The National Transportation Safety Board has been a vocal proponent of the need for better driver monitoring across the industry, pointing to crash investigations involving automation overreliance and poor human-machine interface design.

The net result is a shrinking compliance bubble: what automakers claim about automation must square with the system’s actual behavior, and safety mitigations must work in the chaotic reality of real-world driving, not just in staged demos.

What compliance might look like under the DMV ruling

To meet the ruling, Tesla has some options. Count One: Redefine product names and claims to focus on driver supervision, possibly forcing “Full Self-Driving” to an early retirement or at least a demotion in favor of titles that triangulate SAE Level 2. Second, give disclosures equal prominence with claims on web pages, in-app alerts and retail materials. Third, gate high-level functionality behind explicit consent flows that ensure driver comprehension and demand sustained attention using a combination of robust camera-based monitoring and regular on-road reminders.

An ideal benchmark is when the average driver, reading marketing materials on the fly, leaves with an accurate sense of the scope of the system’s abilities. Footers on a page are not going to cut it when headlines and imagery scream of hands-off automation.

More traffic for whom? Robotaxi pilots versus customer features

The ruling comes as Tesla widens a robotaxi experiment in Austin, where it recently removed safety monitors from a small pilot fleet testing software that is different from what customers have. The divide highlights the core problem: experimental autonomy programs are progressing, but cars you can buy and use on public roads are driver-assistance systems. Any marketing that blurs that barrier is likely to come under scrutiny from regulators.

Investors have long priced Tesla in part on the potential for software-powered, high-margin autonomy. That door has not been shut by this decision, but it does raise the price of imprecision. To scale up automated driving, clearer claims and evidence of safety gains will be needed.

The bottom line for Tesla after the California ruling

The judge’s conclusion that Tesla had deceived the public about Autopilot and Full Self-Driving was a crowning regulatory moment in automated driving. Tesla has 90 days, now, to bridge its marketing with what the technology can do in the real world or face suspended sales again in its most critical U.S. market — and possibly a halt in production at Fremont. The ball is in Tesla’s court, and the industry will be watching.